Notable Submarine Accidents: Difference between revisions

Pbcjohnston (talk | contribs) Moved R-6 info |

Pbcjohnston (talk | contribs) m →Notes |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

=== <big>Notes</big> === | === <big>Notes</big> === | ||

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">The pigboats era of 1900- | <div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">The pigboats era of 1900-1941 is notable for several reasons, not the least of which is the fact that submarine technology was in its infancy; the USN was learning the limits of what this new technology could do and what it couldn't. The pigboats were pathfinders in a very real sense, and sometimes that meant that dangerous unknowns were encountered. When combined with normal human fallibility, those unknowns sometimes resulted in a smashed-up submarine, and at others it unfortunately led to our submarine brethren paying a steep price for their pathfinding service. | ||

This section is meant to highlight some of the notable accidents that befell our Submarine Force during the pigboats era. The purpose is to honor the bravery and sacrifice of the men involved, and to show that the Navy persevered and learned from its mistakes. The technology matured and submarines got safer, but sailing a ship under the sea will never be a safe activity. This list is not all-inclusive, nor will it tell the full tale of each incident. It will give an overview and highlight some of the photographs that Ric has collected over the years. Many of these incidents have been covered in depth by other authors, and when possible we will provide links to books and video that we know will tell the full tale. | This section is meant to highlight some of the notable accidents that befell our Submarine Force during the pigboats era. The purpose is to honor the bravery and sacrifice of the men involved, and to show that the Navy persevered and learned from its mistakes. The technology matured and submarines got safer, but sailing a ship under the sea will never be a safe activity. This list is not all-inclusive, nor will it tell the full tale of each incident. It will give an overview and highlight some of the photographs that Ric has collected over the years. Many of these incidents have been covered in depth by other authors, and when possible we will provide links to books and video that we know will tell the full tale. | ||

Revision as of 10:44, 15 October 2024

Notes

This section is meant to highlight some of the notable accidents that befell our Submarine Force during the pigboats era. The purpose is to honor the bravery and sacrifice of the men involved, and to show that the Navy persevered and learned from its mistakes. The technology matured and submarines got safer, but sailing a ship under the sea will never be a safe activity. This list is not all-inclusive, nor will it tell the full tale of each incident. It will give an overview and highlight some of the photographs that Ric has collected over the years. Many of these incidents have been covered in depth by other authors, and when possible we will provide links to books and video that we know will tell the full tale.

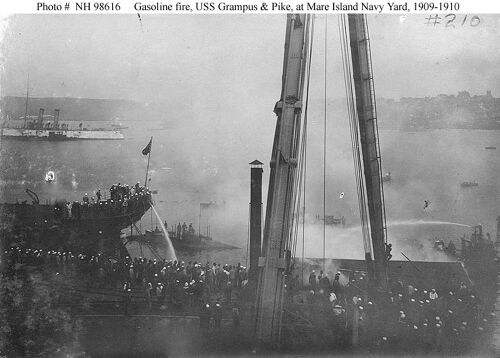

For further information on the men who gave their lives in these incidents, we highly recommend the website On Eternal Patrol, or OEP. Charles Hinman and his team have done an amazing job of gathering information on our deceased shipmates. Please take a look.Grampus (Submarine No. 4) and Pike (Submarine No. 6) gasoline fire, September 19, 1908

For a contemporary newspaper article that goes into depth on this incident, please see this link. Note: please disregard the clerical date error at the top of the NHHC photograph. The fire did happen in 1908.

F-4 (Submarine No. 23), Hull failure during a test dive, March 25, 1915

Several months earlier, the boat had been fitted with an experimental propeller design that was intended to provide maximum thrust at low RPM's. When the captain attempted to power out of the uncontrolled descent, the increased RPM's caused the propellers to cavitate badly and lose thrust. When the boat passed crush depth the hull catastrophically imploded and F-4 sank with all hands. There were no survivors.

Five and a half months later, after a prodigious effort involving unparalleled bravery and incredible ingenuity, F-4 was raised from 306 feet (92.3 m) of water and returned to Honolulu where she was drydocked and inspected. The remains of her crew were removed and given a hero's procession through Honolulu before they were returned to the mainland for burial. After the completion of the accident investigation, F-4 was stripped of any useful equipment and her hulk was towed to Pearl Harbor where it was dropped in the shallow waters of the then unused Magazine Loch. 25 years later it was found that her wreck was in the way of the rapidly expanding Submarine Base so a trench was dug next to the wreck and she was rolled into it. This got her out of the way and allowed the base to continue its expansion. She remains there to this day, just a few yards off berth S13.

PigBoats.COM is proud to display a collection of photographs of her salvage and those are presented here. In addition, the webmasters provided author Jon Humboldt Gates with technical advice for his book Before the Dolphins Guild which tells the story of the loss of the F-4.E-2 (Submarine No. 25), Battery explosion and fire, January 15, 1916

On January 15, 1916 a series of aggressive charge/discharge tests were being run on the new battery, under the supervision of representatives of the Edison company. The boat's commanding officer, LT Charles "Savvy" Cooke had been highly concerned about the battery and the tests that Edison had ordered for it. His apprehensions were dismissed by the overly confident Edison staff. He had been very uneasy that morning and had warned his Chief Electrician to be careful. Just after 1300 that afternoon there was a powerful hydrogen explosion inside the sub. One man was just exiting the after battery hatch when the explosion occurred. It blew him up into the air as if he had been shot from a cannon. Cooke, who had been a few piers over on the tender USS Ozark (Monitor No. 7) having lunch, immediately ran back to the boat and led the effort to reenter the sub to rescue survivors and to get the fire out. He acted bravely with inspiring leadership. By 1600 the resulting fire had been put out and the boat evacuated. Four men had been killed and 10 badly injured.

In the subsequent investigation, the Edison company vigorously denied any culpability in the accident and tried to shift the blame onto Cooke. LT Chester W. Nimitz (yes, that Chester Nimitz) earnestly defended his fellow submariner, and in the end Cooke was absolved of any responsibility. The stain of the affair lingered for a while, but Cooke was eventually assigned to command the brand new USS S-5 (SS-110). His leadership and skills were vindicated by his performance during the sinking of the S-5 during trials in 1920. He kept his crew together and they were all saved.

E-2 was repaired and put back into service and served the Navy well until 1921. For further information on the brave men who were lost that tragic January day in 1916, please see this On Eternal Patrol link.

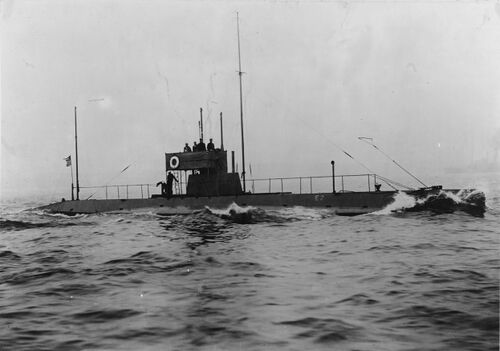

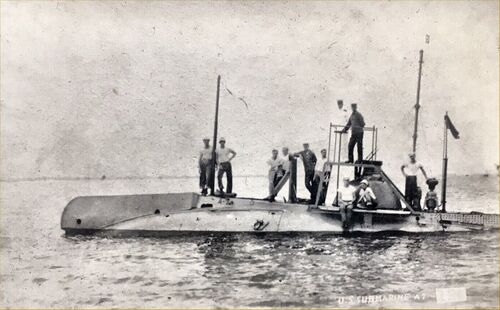

A-7 (Submarine No. 8), Gasoline explosion and fire, July 24, 1917

F-1 (Submarine No. 20), Collision with F-3 (Submarine No. 22), December 17, 1917

O-5 (SS-66), Battery explosion, October 5, 1918

S-5 (SS-110), Accidental flooding during test dive, September 1, 1920

Knowing that there was little hope of being rescued, Cooke led a herculean effort to get the boat back to the surface. Knowing that the torpedo room has hopelessly flooded the crew decided to try to raise the stern above the water by blowing the aft ballast tanks. This procedure tipped the boat upward at a large angle, with approximately 14 feet of the stern now above water. The crew then laboriously started an effort to cut a hole in the thick steel in the aft most compartment, the small and confined tiller room. After a day and a half of back breaking and dangerous work, they only succeeded in cutting a hole three inches in diameter, through which they passed a flag tied to a short pole.

A passing steamer, the SS Alanthus, saw the odd looking "buoy" in the water and stopped to investigate. They hove-to alongside the stern and the Alanthus' captain began a semi-humorous verbal exchange with an exasperated and exhausted Cooke through the tiny hole. When the Alanthus' captain, in traditional maritime fashion, inquired as to the submarine's destination, Cooke bellowed "HELL BY COMPASS!"

The Alanthus' crew flagged down another ship and the combined crews set to work to enlarge the hole. By 0145 on September 3, the hole was barely big enough to start the evacuation of the crew. An hour and fifteen minutes later Cooke was the last man to leave the wrecked submarine. Through perseverance, resolute action, and superb leadership the entire crew had survived with only minor injuries.

Subsequent efforts to salvage the S-5 were unsuccessful, and the wreck sank to the bottom of the Atlantic. The Navy abandoned the boat where she laid. An investigation showed that during the dive Chief Petty Officer Percy Fox, momentarily distracted by other events in the control room, pulled very hard on the large lever used to shut the main air induction valve and in doing so the valve stuck in the open position. Fox was eventually exonerated of blame as it was shown that the design of the valve operating mechanism was poor and prone to jamming.

In July 2001 a NOAA ship rediscovered the wreck and surveyed it using side scan sonar equipment. The wreck remains there to this day, resting in the deep. See this page for more photos.

L-1 (SS-40), Collision with a pilot boat, February 2, 1921

"The four submarines, practicing manoeuvres, alternately diving and steaming on the surface, gambolled like huge dolphins up the coast..." the newspapers reported.

The USS L-1 was under the command of LT Robert Philip Luker. The L-2, by LT John Kennon Jayne, the L-3 by LT Lew Wallace Bagby and the L-9 was commanded by LT Ernest Homer Krueger.

First one submarine and then another would dive and run submerged for a while and get their trim and then run a simulated attack on one of her number and then surface. The next submarine would do the same and so on. This pattern progressed on into the night. When surfaced the submarines adhered to the rules of the road in displaying proper navigational lighting.

The small flotilla progressed up the Delaware coast and well after midnight the group was approaching the Delaware Capes still running their drills. They were about eight miles off Cape Henlopen, near the Overfalls Light Ship, the seas were smooth and the night was very dark.

Captain John H. Kelly, skipper of the pilot boat Philadelphia, saw the small lights out to sea and set off to inquire if the vessel needed a pilot. Due to the darkness of the night and how close to the water's surface the light appeared Kelly misjudged the distance to the L-1 thinking it was a larger ship at a much further distance. At 2:50 AM, before either vessel could react, the bow of the Philadelphia ran up onto the port quarter of the L-1 denting her plates and opening seams. Water began entering the submarine in her engine room but the pumps seemed to be keeping up for a bit.

Kelly passed a tow line to the L-1 but LT Luker was of the opinion he could make shore. Soon the engines stopped and they were not able to be restarted. The Philadelphia took the L-1 in tow and managed to get her behind the breakwater at Lewes, DE. The submarine made it this far before she settled stern first on the bottom between the Queen Anne pier at Lewes, and the end of the breakwater.

Making sure the submarine was as secure as it could be the crew was removed from the ill-fated vessel and taken to various homes around the area and the men were fed and had a warm place to sleep.

Calls were put into the Navy Yard and the fleet tug USS Kalmia (AT-23) was dispatched to Lewes to re-float he L-1. After a few days work in assessing the damage and placing collision matting on the damaged area of the hull the submarine, pumping of the engine room was begun. On February 8 the L-1 was slung between the Kalmia and the Navy tug Modoc (YT-16) and the 85 mile trip up to Philadelphia began.

Unfortunately, there is little or no more readily available information about the repair of the L-1 or its return to the fleet. This is just one of those little known or reported happenings that doesn't make it into the official histories of ships.

Thanks to Ron Reeves for finding the commanding officers of the other three submarines.

| Lieutenant Robert Philip Luker, CO | Lieutenant P. S. Cochran, XO | Alfred S. Worthine, Philadelphia | Harold Frank Aldrich, Wellsville, NY | Rupert Beaty, Cabot, AR |

| Dominico Bnccino (sp?), New York City, NY | Leetis Cobb, West Baden, IN | Gus Farmer, Mayodan, NC | Julius Jacob Fieghene, Berwyn, PA | Chas Wesley Fillmore, Boone, LA |

| Ralph Tracy Hill, Los Angeles, CA | Julius Loson Hicks, Etowah, TN | William Joseph Leyhan, Louisville. KY | William Oscar Lindquist, Hayward, WI | Clarence E. Mitchell, Houston, TX |

| George Quade, Anacostia, D.C. | Frank Charles Quaver, White Haven, PA | Alphonso Joseph Souey, Danvers, MA | Milo Bernard Thiese, Oelwein, IA | Ralph Marion Wycroff, Toppenish, WA |

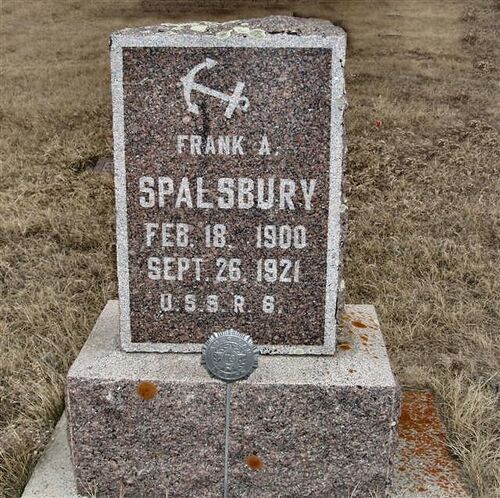

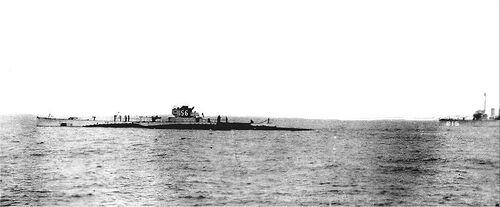

R-6 (SS-83), Accidental flooding through torpedo tube, September 26, 1921

All submarines have an interlock system that prevents both the breech and muzzle doors of the torpedo tube from being opened at the same time. This interlock system had failed for one of the tubes and the crew was unaware of this. It is unclear from the reports from that time why the interlock failed but apparently when the Torpedomen opened the breech door the muzzle door was open or partially open and water began to rapidly flood the torpedo room.

The startled crew ran from the room into the forward battery compartment. Others escaped through the torpedo room deck hatch. One man, seeing what was happening, raced to the deck and chopped the mooring lines that held the R-6 to the nest of submarines moored to the tender Camden. The weight of the flooded submarine would have pulled the other submarines under as well.

The reports say that Electrician's Mate 2nd Class Frank A. Spalsbury and Seaman John E. Dreffien were among those aboard. Witnesses say they heard a small explosion (likely from a shorted forward battery) inside the submarine and at that time Spalsbury was seen to be launched into the air from the conning tower hatch from which he was trying to escape and land in the water. At first it was thought that Seaman Dreffien and one other were trapped inside the submarine and had managed to secure themselves in a compartment.

The submarine continued to flood and reports also say that LT Chambers was the last officer to leave the submarine. He began at once to help other men in the water to safety and didn't stop until all men were assisted. The R-6 settled in 35 feet of water on the harbor bottom.

At first light work began in hopes of saving those inside the submarine. A large crane that was working in the harbor was brought over and divers went down to attach ropes to the submarine. They also tapped on the hull to see if there was any response from inside. Over the night one of the missing men had been located so it was only Seaman John Dreffein unaccounted for and presumed inside the hull. The submarine proved to be too heavy for the crane to lift.

Courtesy of FindAGrave.com

Several days later, on the 29th, Spalsbury's body was found on the bottom of the harbor only about ten feet from his sunken submarine.

Frank Amzi Spalsbury was born and raised in a modest farming town in northwest North Dakota named Powers Lake. Born on February 18, 1900, he was the son of Arthur Amzi "Arthur W." Spalsbury and Elizabeth Ann "Bessie" Hall Spalsbury. He had a younger brother named Edward Arthur and another named Alan W. His father was a stone mason. According to Powers Lake town historian Larry Tinjum, the father was responsible for most of the town's cement work in the early years of the town's creation. At age 18 with WW I raging in Europe, Frank registered for the draft but joined the Navy. He had risen to the rank of Electrician's Mate 2nd Class at the time of his death. He was returned to Powers Lake and is buried at Bethel Cemetery just to the southwest of the town. He lies there under a beautiful red granite head stone.

Finally on October 13, 1921 the R-6 was refloated with the assistance of the USS Cardinal AM-6 and sister ship R-10 who provided the high-pressure air to expel the water from the R-6's hull.

Once the R-6 was back on the surface and crew could get aboard, the body of Seaman John E. Dreffein was located. Little can be found about this man. He seems to have been born in Three Oaks, Michigan on August 27, 1898. He was buried in the Rock Island National Cemetery in Rock Island, Illinois, Plot: SE–453. There seem to be a number of Dreffein names in the Illinois area so it is quite possible there are family in that area.

Once the R-6 was repaired she was sent back to the fleet for duty. She served the Navy quite well (with a period in reserve) until the end of her service life in the fall of 1945.

S-6 (SS-111), Collision with a destroyer, 1922

O-5 (SS-66), Collision with a merchant ship, October 28, 1923

S-51 (SS-162), Collision with merchant ship, September 25, 1925

In addition, a granddaughter of one of the lost crewmen maintains an excellent informational site on the accident, which can be accessed at the enclosed link.

S-4 (SS-109), Collision with USCGC Paulding, December 17, 1927

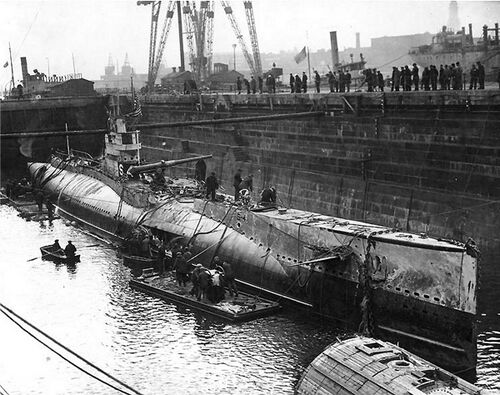

The boat was subsequently salvaged, and is shown here in drydock at the Boston Navy Yard, March 19, 1928 after three months of herculean work by the salvage team. She was partially reconditioned, but was not returned to full service. Instead, she was used as a test bed to develop new technologies and techniques for submarine escape, rescue, and salvage. She was finally decommissioned in 1933 and eventually scrapped. The S-4 tragedy left an enduring legacy with the Submarine Service. Her loss and the inability to rescue the trapped men prompted the Navy to undertake a serious review of submarine rescue and salvage, which lead to the development of new techniques and technologies. The Momsen Lung escape apparatus, escape trunks, salvage air connections, improved salvage capabilities, and the famous McCann Rescue Chamber all came about because of the S-4 incident. Her crew's sacrifice directly lead to saving the lives of their brother submariners in subsequent years. They did not die in vain.

We have a series of photos that depict the subsequent salvage efforts at this link. The webmasters can also highly recommend the book Seventeen Fathoms Deep: The Saga of the Submarine S-4 Disaster by historian Joseph A. Williams. The webmasters were happy to act as technical advisors for the book. Mr. Williams wrote an incredible tale of danger, tragedy, perseverance, and ingenuity. You will not be disappointed with this true story.Squalus (SS-192), Equipment failure during a test dive, May 23, 1939

What followed was an epic story of the courage and tenacity of our sea service. In the first, and only, operational use of the McCann Rescue Chamber in the USN, all 33 men in the forward compartments were rescued and brought to the surface. Over the next three and a half months the Squalus was salvaged under very difficult conditions and returned to Portsmouth for repair and refurbishment. She was renamed Sailfish (SS-192) and returned to full service. She went on to have a fine war record.

PigBoats.COM has compiled a collection of rescue and salvage photos of this incident and they can be found at this link.

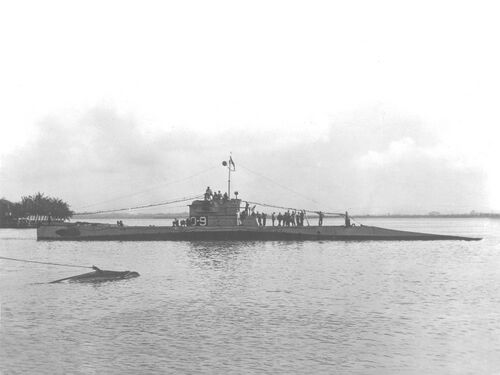

O-9 (SS-70), Hull failure during a test dive, June 20, 1941

In 1940, noting with alarm the deteriorating war situation in Europe, orders were issued to reactivate the mothballed O-boats for use as training vessels for the anticipated huge increase in personnel for a rapidly expanding Submarine Service. O-9 (SS-70) was one of the boats earmarked for further service. The rushed nature of the order, combined with the large number of subs and ships being pulled out of reserve severely stretched the capabilities of the east coast shipyards. The O-9 needed thorough and meticulous tender-loving-care, but that work was rushed and inadequate, and by the time she was recommissioned in April 1941 she still faced numerous materiel condition challenges.

On June 19, 1941 O-9 got underway from Submarine Base New London and headed out to sea accompanied by her sister boats O-6 (SS-67) and O-10 (SS-71). They were to conduct deep submergence trials off the Isle of Shoals in a designated submarine operating area. O-6 and O-10 successfully completed their dives early on the morning of June 20. O-9 dove at 0837 that morning and was never heard from again. Her failure to surface was noted by her sister boats at 0940 and the alarm was sent out. A massive search and rescue operation was immediately begun that included all submarines in the area along with the submarine rescue vessels USS Chewink (ASR-3) and the well-known USS Falcon (ASR-2).

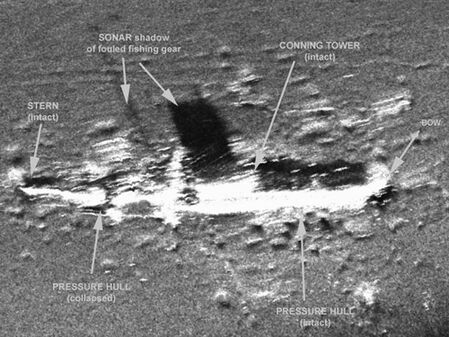

Grapnel dragging located the boat on the bottom at the ominous depth of over 400 feet. O-9's test depth was only 200 feet. Rescue operations were immediately begun, and divers put over the side. The extreme depth resulted in only two divers making it to the bottom at 432 feet, but they found that the entire after part of the boat from the conning tower aft had imploded, with the front half clearly flooded. She had succumbed to the sea. The crew was dead.

The extreme conditions of working at 432 feet forced the commanding officer of the rescue force, Rear Admiral Richard Edwards, to call a halt to the efforts and his decision was backed up by the Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox on June 22. Later that day a solemn funeral service was held aboard the USS Triton (SS-201), one of the accompanying submarines, and the Navy and the nation said farewell to their shipmates. The O-9 and her crew of 33 were left were they laid, and no further attempt was made to salvage her. The cause of her loss was never determined exactly, but it was assumed that it was related to her poor materiel condition. This was not the Navy's finest hour. This loss was likely entirely preventable.

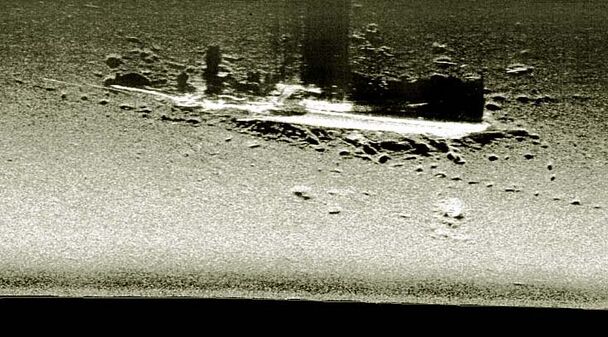

On September 20, 1997 an expedition sponsored by Klein Marine Systems succeeded in rediscovering the wreck using a towed side-scan sonar system. A subsequent visit to the site by NOAA conducted a thorough sonar survey and they produced the following images.

-

Photo courtesy of Klein Marine Systems via Navsource.

-

Photo courtesy of NOAA.

The site has been designated as an official military burial ground with the exact location held in secret. For information on the O-9's crew, please see the On Eternal Patrol page for the O-9. Rest in peace brothers.

Page created by:

Ric Hedman & David Johnston

1999 - 2023 - PigBoats.COM©

Mountlake Terrace, WA, Norfolk, VA

webmaster@pigboats.com