Wilkins Arctic Submarine Nautilus: Difference between revisions

Pbcjohnston (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

Pbcjohnston (talk | contribs) (Added photo and updated text) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">In early 1931, Australian explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins and American arctic pioneer Lincoln Ellsworth teamed up with the idea of taking a submarine under the ice to the North Pole. The joint venture was known as the Wilkins-Ellsworth Trans-Arctic Expedition, and after raising capital from various investors including famous newspaper man William Randolph Hearst, Wilkins approached submarine engineer and industrialist Simon Lake to assist with the task. | <div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">In early 1931, Australian explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins and American arctic pioneer Lincoln Ellsworth teamed up with the idea of taking a submarine under the ice to the North Pole. The joint venture was known as the Wilkins-Ellsworth Trans-Arctic Expedition, and after raising capital from various investors including famous newspaper man William Randolph Hearst, Wilkins approached submarine engineer and industrialist Simon Lake to assist with the task. | ||

At first, Lake offered Wilkins his old submarine [[Defender|'''Defender''']], but Wilkins immediately judged the old boat to be too small for the arduous task. Wilkins and Lake approached the Navy and were able to secure an agreement to lease the decommissioned submarine ex-USS O-12 (SS-73), which was laying in reserve at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. This would be an ideal situation for Lake, as his company had built the O-12 during WWI and he was intimately familiar with her design. The obsolete O-12 was no longer wanted by the Navy so they transferred ownership of the boat to the U.S. Shipping Board, who then agreed to lease the boat back to the newly formed Lake & Danenhower, Inc. for conversion for Wilkins. Former USN submarine commander Sloan Danenhower was now a business associate of Simon Lake, and his expertise got him the job of being the expedition's submarine skipper. The Shipping Board agreed to lease the boat for one dollar for one year, with the only other stipulation being that when the expedition was completed | At first, Lake offered Wilkins his old submarine [[Defender|'''Defender''']], but Wilkins immediately judged the old boat to be too small for the arduous task. Wilkins and Lake approached the Navy and were able to secure an agreement to lease the decommissioned submarine ex-USS O-12 (SS-73), which was laying in reserve at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. This would be an ideal situation for Lake, as his company had built the O-12 during WWI and he was intimately familiar with her design. The obsolete O-12 was no longer wanted by the Navy so they transferred ownership of the boat to the U.S. Shipping Board, who then agreed to lease the boat back to the newly formed Lake & Danenhower, Inc. for conversion for Wilkins. Former USN submarine commander Sloan Danenhower was now a business associate of Simon Lake, and his expertise got him the job of being the expedition's submarine skipper. The Shipping Board agreed to lease the boat for one dollar for one year, with the only other stipulation being that when the expedition was completed the boat be returned to Navy control or be scuttled in water at least 1,200 feet deep (370 m), so that it could not be used in military operations against the United States. | ||

Lake was granted the rights to use the Philadelphia Navy Yard drydock for the initial conversion work and he used that time to strip the exterior of the boat down to the main deck. He also demilitarized the boat by cutting off the torpedo tubes where they penetrated into the torpedo room. The portions that remained were permanently sealed up with flanges. A diver lock-out chamber was added to the torpedo room, along with a hatch in the bottom to allow the diver to exit and to lower scientific instruments into the water. The rest of the torpedo handling equipment was removed and the remainder of the space turned into a laboratory. The boat's bow was reinforced with concrete and extra steel so that a collision with the ice would not damage it. Other interior refurbishment work was done on the boat, as she had been sitting in reserve for six years and was in bad shape. | Lake was granted the rights to use the Philadelphia Navy Yard drydock for the initial conversion work and he used that time to strip the exterior of the boat down to the main deck. He also demilitarized the boat by cutting off the torpedo tubes where they penetrated into the torpedo room. The portions that remained were permanently sealed up with flanges. A diver lock-out chamber was added to the torpedo room, along with a hatch in the bottom to allow the diver to exit and to lower scientific instruments into the water. The rest of the torpedo handling equipment was removed and the remainder of the space turned into a laboratory. The boat's bow was reinforced with concrete and extra steel so that a collision with the ice would not damage it. Other interior refurbishment work was done on the boat, as she had been sitting in reserve for six years and was in bad shape. | ||

She was then towed to the John H. Mathis & Company shipyard in Camden, NJ. where the rest of the conversion work was done. A large ice skid, somewhat like an upside down ski, was built over the main deck and the space underneath in closed in. Other experimental features were added like ice drills that were intended to bore through the ice to bring air to the submerged submarine, a hydraulic spar on the tip of the bow to cushion collisions with the ice, and an extendable skid to provide a shock-absorber effect under the ice. Most of these contraptions were the product of Simon Lake's rather fertile imagination. They were of dubious | She was then towed to the John H. Mathis & Company shipyard in Camden, NJ and eventually to a third yard in Yonkers, NY. where the rest of the conversion work was done. A large ice skid, somewhat like an upside down ski, was built over the main deck and the space underneath in closed in. Other experimental features were added like ice drills that were intended to bore through the ice to bring air to the submerged submarine, a hydraulic spar on the tip of the bow to cushion collisions with the ice, and an extendable skid to provide a shock-absorber effect under the ice. Most of these contraptions were the product of Simon Lake's rather fertile imagination. They were of dubious value and were only barely tested prior to the boat's departure for the Arctic. | ||

In true Simon Lake fashion, the work to convert the boat, now named Nautilus (inspired by Lake's fascination with Jules Verne), took much longer than anticipated and ran considerably over budget. They were pressed for time, as it was the desire of Wilkins and Ellsworth to get the expedition going during the Arctic summer, when conditions were much more favorable. Badly needed work to refurbish the engines, motors, hydraulics, and structure was either rushed through or was entirely deferred. This would prove to be a fateful decision. | In true Simon Lake fashion, the work to convert the boat, now named Nautilus (inspired by Lake's fascination with Jules Verne), took much longer than anticipated and ran considerably over budget. They were pressed for time, as it was the desire of Wilkins and Ellsworth to get the expedition going during the Arctic summer, when conditions were much more favorable. Badly needed work to refurbish the engines, motors, hydraulics, and structure was either rushed through or was entirely deferred. This would prove to be a fateful decision. | ||

The overall design of the conversion work reflected Lake's naivete about Arctic conditions, and his predilection towards a romantic and unrealistic view of the rigors of exploration. | The overall design of the conversion work reflected Lake's naivete about Arctic conditions, and his predilection towards a romantic and unrealistic view of the rigors of exploration. The whole concept of the submarine running along under the ice pack on its superstructure skid was based on the false idea that the Arctic ice pack was smooth and flat underneath like that of a frozen freshwater lake. Nothing could be further from the truth. Incredibly, the boat was not equipped with heaters, and the crew suffered terribly from the bone chilling cold that radiated inward from the steel hull. Freshwater in tanks routinely froze solid and there was only one toilet for the entire crew, and that was inconveniently placed between the main engines. The ice drill proved very difficult to use in dockside tests and it failed routinely to bore into test blocks of ice. In the arctic against the rock hard ice found there the drill was completely useless and the trunk leaked through the circumferential seal. For some reason, the bow planes had been removed by Lake in Philadelphia, leaving only the stern planes for underwater control, a problematic state of operation at best. The engines failed on the trip across the Atlantic, and they had to be hurriedly overhauled in England before departing for the polar region | ||

Despite the issues, Wilkins pressed on with the expedition, driven by the pressure of his investors and the overbearing influence of Hearst. They made it to the ice pack and even operated under it for short periods. They gathered | Despite the issues, Wilkins pressed on with the expedition, driven by the pressure of his investors and the overbearing influence of Hearst. They made it to the ice pack and even operated under it for short periods. They gathered a lot of useful scientific data, but on an overall basis the expedition was nearly a total failure, with the crew nearly in an mutinous state from the horrid conditions onboard. There were also unsubstantiated reports of deliberate sabotage by a worried crew. The mechanical difficulties encountered by the expedition were more likely due to the poor material condition of the boat and to Lake's contraptions. The expedition ended in a Norwegian fjord near Bergen, where Wilkins and Danenhower lived up to the terms of the contract and scuttled the boat in deep water. It was later discovered and surveyed by Norwegian divers in 1981. | ||

See the photos and video below for a more complete story of the conversion work and the pioneering expedition. Also [[Danenhower Arctic expedition article|'''see this page''']] for a reprint of an article by Sloan Danenhower describing the conversion work done to the O-12/Nautilus. ''Special note''... the drawings below come from the Syracuse American News Paper, Sunday March 1, 1931 edition. It is likely that the paper has gone out of existence. No mention of it still being in publication could be found anywhere. It may have | See the photos and video below for a more complete story of the conversion work and the pioneering expedition. Also [[Danenhower Arctic expedition article|'''see this page''']] for a reprint of an article by Sloan Danenhower describing the conversion work done to the O-12/Nautilus. ''Special note''... the drawings below come from the Syracuse American News Paper, Sunday March 1, 1931 edition. It is likely that the paper has gone out of existence. No mention of it still being in publication could be found anywhere. It may have | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | [[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | ||

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#000000"> | |||

===<big>Conversion work and initial sea trials</big>=== | |||

</div> | |||

<br> | |||

[[File:O-12 Nautilus Conversion.jpg|left|500px]] | [[File:O-12 Nautilus Conversion.jpg|left|500px]] | ||

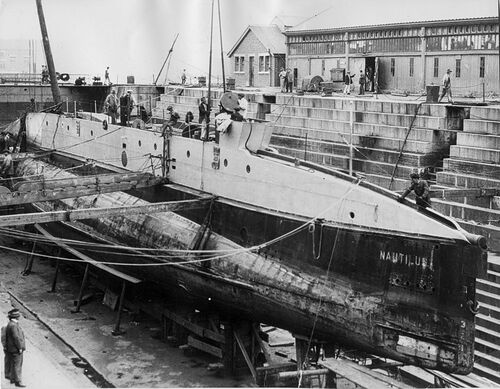

The former O-12 in drydock at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on December 12, 1930, undergoing conversion for the Wilkins arctic expedition. She would be renamed Nautilus. At this point the Navy ostensibly retained ownership of the boat through the U.S. Shipping Board, with the boat leased her to Lake & Danenhower, Inc. for the expedition. Simon Lake and Sloan Danenhower were allowed to make any modifications necessary to the boat, as it was understood that she would never return to naval service. In this photo Lake employees are working topside, having removed the conning tower fairwater, periscopes, and masts, leaving only the bridge access trunk. An extensive superstructure would be built above the main deck. Her torpedo room was being converted into a diver lockout chamber, a scientific instrument "moon pool", and laboratory. The rest of the boat would get refurbishment as well. | The former O-12 in drydock at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on December 12, 1930, undergoing conversion for the Wilkins arctic expedition. She would be renamed Nautilus. At this point the Navy ostensibly retained ownership of the boat through the U.S. Shipping Board, with the boat leased her to Lake & Danenhower, Inc. for the expedition. Simon Lake and Sloan Danenhower were allowed to make any modifications necessary to the boat, as it was understood that she would never return to naval service. In this photo Lake employees are working topside, having removed the conning tower fairwater, periscopes, and masts, leaving only the bridge access trunk. An extensive superstructure would be built above the main deck. Her torpedo room was being converted into a diver lockout chamber, a scientific instrument "moon pool", and laboratory. The rest of the boat would get refurbishment as well. | ||

<small>Original photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.</small> | <small>Original photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.</small> | ||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | |||

[[File:Wilkins Leica advertisement.jpg|left|500px]] | |||

Wilkins and Ellsworth used a variety of methods to raise money for the expedition. A cooperative arrangement with Leica brought in money and also helped to boost sales for the camera manufacturer. The expedition generated a lot of interest amongst the public in many countries. | |||

<small>Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.</small> | |||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | [[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | ||

| Line 55: | Line 67: | ||

[[File:O-12 wilkins1.jpg|left|500px]] | [[File:O-12 wilkins1.jpg|left|500px]] | ||

This from the port side shows Nautilus after the completion of the Arctic conversion work, May 25, 1931. She had an all-civilian crew, captained by Sloan Danenhower, a former U.S. Navy officer and associate of Simon Lake. The newly built ice sled superstructure can be seen atop the former main deck line. The superstructure forward contained non-watertight working compartments for scientists and divers, but | This from the port side shows Nautilus after the completion of the Arctic conversion work, May 25, 1931. She had an all-civilian crew, captained by Sloan Danenhower, a former U.S. Navy officer and associate of Simon Lake. The newly built ice sled superstructure can be seen atop the former main deck line. The superstructure forward contained non-watertight working compartments for scientists and divers, but these compartments could only be used while the boat was surfaced. They had to have been of dubious utility at best. | ||

<small>Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman</small> | <small>Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman</small> | ||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | [[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | ||

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#000000"> | |||

===<big>The voyage across the Atlantic</big>=== | |||

</div> | |||

<br> | |||

[[File:Wilkins Nautilus crew.jpg|left|500px]] | |||

A photo of the crew just before leaving New York City in June 1931 on the first leg of the voyage. From left to right, back row: LT H.W. Ross, USN, Harry Zoelter (oiler), Sir Hubert Wilkins (expedition leader), John A. Janson (oiler), Sloan Danenhower (Captain), H. Rothschild [top] (cook), J. Strohm [below] (machinist), H. Carl Schnetter (engineer), Clarence D. Holland (Asst. Engineer). Left to right, front row: Frank D. Shaw (Chief Engineer), F.A. Blumberg (Chief Electrician), Raymond E. Meyers (radioman), Cornelius P. Royster (electrician), and Edward J. Clark (quartermaster). | |||

Note that this is not the entire crew. Notably missing in this photo is diver Frank Crilley, and the second officer Isaac Schlossbach. It is not known what function LT Ross fulfilled, or whether he made the entire voyage with the boat. Some of these other men did not finish the trip. Some quit after the voyage across the Atlantic, and others were hired in England to make up for the losses. | |||

<small>Photo provided by the late MMCM(SS) Rick Larson, USN (Ret.)</small> | |||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | |||

[[File:Wilkins Nautilus interior crew.jpg|left|500px]] | |||

This photo was likely taken during the transit across the Atlantic, June 1931. From left to right is believed to be H. Carl Schnetter, engineer, oiler John A. Janson, and oiler Harry Zoelter. An unidentified man is seen through the doorway at rear of photo. Life looks dirty and grim. One of the many complaints by the crew was that the conversion work left very few places for the crew to sit down, leaving them standing for most of the time they were awake, even while eating. There were not enough bunks for the entire crew, so they were "hot-racking", meaning that when one man went on watch and vacated a bunk, one man going off-watch occupied the bunk. | |||

<small>Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.</small> | |||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | |||

[[File:Wilkins radiogram form.jpg|left|500px]] | |||

A radiogram form used to Morse code record messages received from the Nautilus during her voyage. One of the many problems facing the expedition was inadequate and poorly maintained radio equipment that failed regularly. Communications with the boat were spotty at best, leaving long periods when nothing was heard from the crew, raising concern. | |||

<small>Image courtesy of James H. Johnson.</small> | |||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | |||

[[File:O-12 wilkins3.jpg|left|500px]] | [[File:O-12 wilkins3.jpg|left|500px]] | ||

A view of the Nautilus underway at sea in the Atlantic, June 14, 1931, alongside the battleship USS Wyoming (BB-32). The boat was transiting to England on the first leg of her Arctic voyage. Rough seas had battered the small submarine, and both engines had failed leaving her adrift. Danenhower called for help and the Navy came to the rescue. The Wyoming took her under tow to Cork, Ireland. | A view of the Nautilus underway at sea in the Atlantic, June 14, 1931, alongside the battleship USS Wyoming (BB-32). The boat was transiting to England on the first leg of her Arctic voyage. Rough seas had battered the small submarine, and both engines had failed leaving her adrift. Danenhower called for help and the Navy came to the rescue. The Wyoming took her under tow to Cork, Ireland. | ||

| Line 86: | Line 126: | ||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | [[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | ||

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#000000"> | |||

===<big>In the ice pack</big>=== | |||

</div> | |||

<br> | |||

[[File:Wilkins Nautilus crew on ice.jpg|left|500px]] | |||

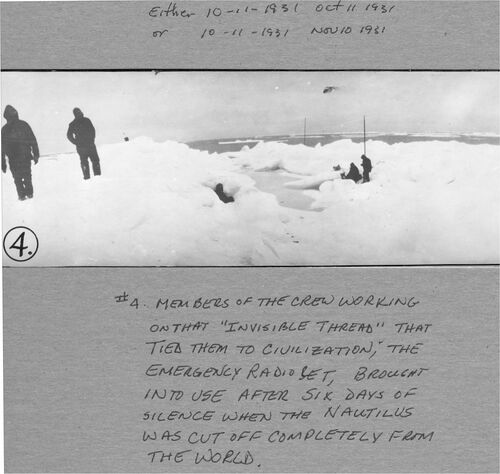

A portion of the Nautilus crew on the ice pack, October 11, 1931. They are trying to set up an emergency radio transmitter to get word out to an anxious world that they were still exploring. | |||

<small>Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.</small> | |||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | |||

[[File:Wilkins Nautilus Crilley.jpg|left|500px]] | |||

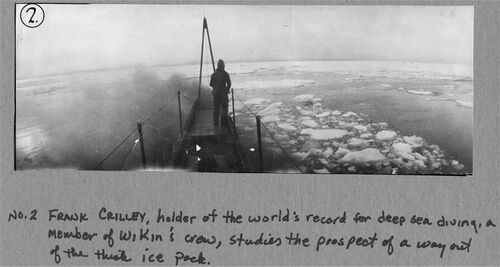

Expedition diver Frank Crilley on the bow of the Nautilus overlooking the pancake and pack ice confronting the boat, October 1931. A Navy Reservist, Crilley participated in the Wilkins Expedition in between stints of active duty with the Navy. | |||

Crilley was a Navy diver of great renown. He worked on George Stillson's team that refined and developed the famous Mk 5 diving dress for the Navy. He was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Coolidge for his near super-human efforts during the [[F-4 salvage|'''F-4 salvage operation in 1915''']]. He later participated in the salvage of the submarines [[S-51 salvage|'''USS S-51 (SS-162)''']] in 1925/1926, and the [[S-4 salvage|'''S-4 (SS-109)''']] in 1927/1928. For his work on the S-4 operation he was awarded the Navy Cross. | |||

<small>Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.</small> | |||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | |||

[[File:Wilkins Nautilus in the ice.jpg|left|500px]] | |||

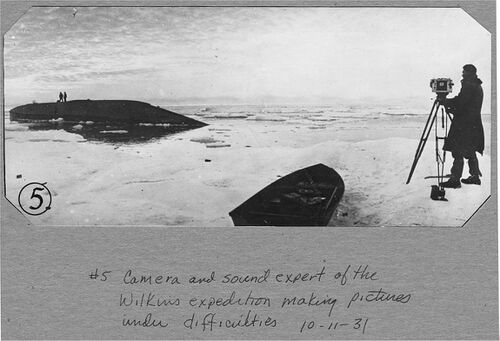

On October 11, 1931 the Nautilus put men out on the ice cap for several reasons, one of which was to take a movie of the boat attempting to submerge under the ice. The Nautilus can be seen in the left background, and the camera man on the right, with a rowboat moored at his feet. This was a truly gutsy move on behalf of the camera man, because if the boat encountered difficulty under the ice and sank or became disabled, he would be dead in a few hours. Brave man indeed! | |||

<small> | <small>Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.</small> | ||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | [[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | ||

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#000000"> | |||

===<big>After the voyage</big>=== | |||

</div> | |||

<br> | |||

[[File:Wilkins Nautilus crew 2.jpg|left|500px]] | |||

Caption from a local newspaper: ''"Home from the perilous dash---in polar bound submarine. Eleven members of the crew of the Polar-Bound submarine Nautilus. Arriving on the S.S. American Banker today (Monday) following the near fatal culmination of their daring dash through the Arctic Circle. Although the party did not cross the pole, plans are already progressing for another attempt in a more adequately equipped submarine."'' This photo was likely taken in New York City on October 5, 1931. From left to right front row: Frank D. Shaw, H. Carl Schnetter, Clearance D. Holland, Frank Crilley, and Raymond E. Meyers. Back row, left to right: Harry Zoelter, Raymond Drakio, Cornleius Royster, Vadien Stayrakov, Edward Clark, John A. Janson. | |||

Once again this is not the whole crew, notably Wilkins, Danenhower, and Schlossbach are not present. | |||

<small>Photo contributed by TMC(SS) Donald W. DeCoster, USN (Ret.), now in the private collection of Ric Hedman.</small> | |||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | |||

{{#ev:youtube|id=8AbtCE-sePc|alignment=left|dimensions=500x300}} | |||

This is a documentary from the Mustard Channel on YouTube. It gives an excellent overview of the Wilkins-Ellsworth Trans-Arctic Expedition and includes some superb CGI graphics of the Nautilus. We can also recommend the other videos on the Mustard Channel, although they mostly cover aviation stories. You won't be disappointed. | |||

<small>Video courtesy of the Mustard Channel on Youtube.</small> | |||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | [[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | ||

Revision as of 15:06, 23 April 2024

Notes

At first, Lake offered Wilkins his old submarine Defender, but Wilkins immediately judged the old boat to be too small for the arduous task. Wilkins and Lake approached the Navy and were able to secure an agreement to lease the decommissioned submarine ex-USS O-12 (SS-73), which was laying in reserve at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. This would be an ideal situation for Lake, as his company had built the O-12 during WWI and he was intimately familiar with her design. The obsolete O-12 was no longer wanted by the Navy so they transferred ownership of the boat to the U.S. Shipping Board, who then agreed to lease the boat back to the newly formed Lake & Danenhower, Inc. for conversion for Wilkins. Former USN submarine commander Sloan Danenhower was now a business associate of Simon Lake, and his expertise got him the job of being the expedition's submarine skipper. The Shipping Board agreed to lease the boat for one dollar for one year, with the only other stipulation being that when the expedition was completed the boat be returned to Navy control or be scuttled in water at least 1,200 feet deep (370 m), so that it could not be used in military operations against the United States.

Lake was granted the rights to use the Philadelphia Navy Yard drydock for the initial conversion work and he used that time to strip the exterior of the boat down to the main deck. He also demilitarized the boat by cutting off the torpedo tubes where they penetrated into the torpedo room. The portions that remained were permanently sealed up with flanges. A diver lock-out chamber was added to the torpedo room, along with a hatch in the bottom to allow the diver to exit and to lower scientific instruments into the water. The rest of the torpedo handling equipment was removed and the remainder of the space turned into a laboratory. The boat's bow was reinforced with concrete and extra steel so that a collision with the ice would not damage it. Other interior refurbishment work was done on the boat, as she had been sitting in reserve for six years and was in bad shape.

She was then towed to the John H. Mathis & Company shipyard in Camden, NJ and eventually to a third yard in Yonkers, NY. where the rest of the conversion work was done. A large ice skid, somewhat like an upside down ski, was built over the main deck and the space underneath in closed in. Other experimental features were added like ice drills that were intended to bore through the ice to bring air to the submerged submarine, a hydraulic spar on the tip of the bow to cushion collisions with the ice, and an extendable skid to provide a shock-absorber effect under the ice. Most of these contraptions were the product of Simon Lake's rather fertile imagination. They were of dubious value and were only barely tested prior to the boat's departure for the Arctic.

In true Simon Lake fashion, the work to convert the boat, now named Nautilus (inspired by Lake's fascination with Jules Verne), took much longer than anticipated and ran considerably over budget. They were pressed for time, as it was the desire of Wilkins and Ellsworth to get the expedition going during the Arctic summer, when conditions were much more favorable. Badly needed work to refurbish the engines, motors, hydraulics, and structure was either rushed through or was entirely deferred. This would prove to be a fateful decision.

The overall design of the conversion work reflected Lake's naivete about Arctic conditions, and his predilection towards a romantic and unrealistic view of the rigors of exploration. The whole concept of the submarine running along under the ice pack on its superstructure skid was based on the false idea that the Arctic ice pack was smooth and flat underneath like that of a frozen freshwater lake. Nothing could be further from the truth. Incredibly, the boat was not equipped with heaters, and the crew suffered terribly from the bone chilling cold that radiated inward from the steel hull. Freshwater in tanks routinely froze solid and there was only one toilet for the entire crew, and that was inconveniently placed between the main engines. The ice drill proved very difficult to use in dockside tests and it failed routinely to bore into test blocks of ice. In the arctic against the rock hard ice found there the drill was completely useless and the trunk leaked through the circumferential seal. For some reason, the bow planes had been removed by Lake in Philadelphia, leaving only the stern planes for underwater control, a problematic state of operation at best. The engines failed on the trip across the Atlantic, and they had to be hurriedly overhauled in England before departing for the polar region

Despite the issues, Wilkins pressed on with the expedition, driven by the pressure of his investors and the overbearing influence of Hearst. They made it to the ice pack and even operated under it for short periods. They gathered a lot of useful scientific data, but on an overall basis the expedition was nearly a total failure, with the crew nearly in an mutinous state from the horrid conditions onboard. There were also unsubstantiated reports of deliberate sabotage by a worried crew. The mechanical difficulties encountered by the expedition were more likely due to the poor material condition of the boat and to Lake's contraptions. The expedition ended in a Norwegian fjord near Bergen, where Wilkins and Danenhower lived up to the terms of the contract and scuttled the boat in deep water. It was later discovered and surveyed by Norwegian divers in 1981.

See the photos and video below for a more complete story of the conversion work and the pioneering expedition. Also see this page for a reprint of an article by Sloan Danenhower describing the conversion work done to the O-12/Nautilus. Special note... the drawings below come from the Syracuse American News Paper, Sunday March 1, 1931 edition. It is likely that the paper has gone out of existence. No mention of it still being in publication could be found anywhere. It may have been absorbed by another paper or just gone out of business as many papers have.

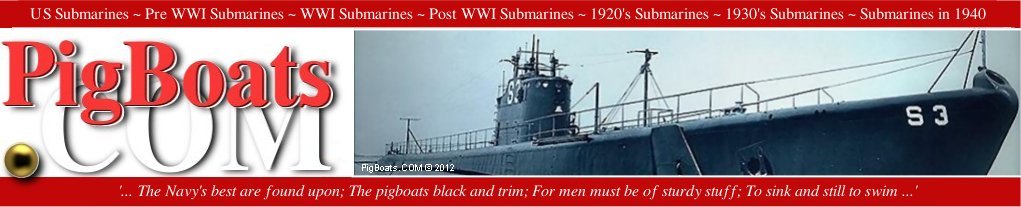

Nautilus configuration drawings

Courtesy of the Syracuse American News Paper, Sunday March 1, 1931 edition.

Conversion work and initial sea trials

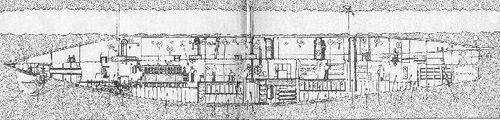

The former O-12 in drydock at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on December 12, 1930, undergoing conversion for the Wilkins arctic expedition. She would be renamed Nautilus. At this point the Navy ostensibly retained ownership of the boat through the U.S. Shipping Board, with the boat leased her to Lake & Danenhower, Inc. for the expedition. Simon Lake and Sloan Danenhower were allowed to make any modifications necessary to the boat, as it was understood that she would never return to naval service. In this photo Lake employees are working topside, having removed the conning tower fairwater, periscopes, and masts, leaving only the bridge access trunk. An extensive superstructure would be built above the main deck. Her torpedo room was being converted into a diver lockout chamber, a scientific instrument "moon pool", and laboratory. The rest of the boat would get refurbishment as well.

Original photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

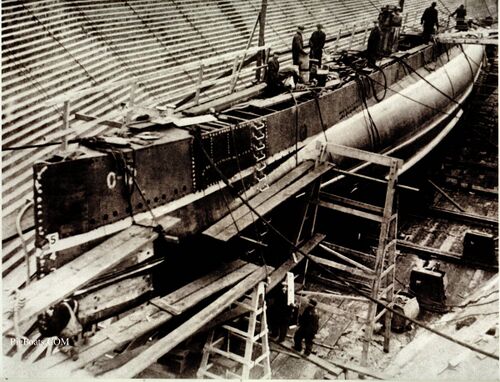

Wilkins and Ellsworth used a variety of methods to raise money for the expedition. A cooperative arrangement with Leica brought in money and also helped to boost sales for the camera manufacturer. The expedition generated a lot of interest amongst the public in many countries.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Simon Lake inspecting the operation of the ice drill/extendable access trunk during the conversion work at a shipyard in Yonkers, New York, February, 1931. This was to be an integral part of the equipment for the sub. The drill was to allow the submarine to bore a hole up to the surface and allow the crew to draw in fresh air to breathe and run the diesels to charge batteries. It was also intended to allow the crew to exit the sub and climb on to the ice surface. A temporary frame was erected above the drill that held blocks of ice. Even in this relatively benign test the drill did not work the way Lake intended it to, jamming frequently. With his boundless enthusiasm Lake brushed aside any concerns that Wilkins had concerning the contraption. He continued to tinker with it right up until the submarine departed for the Arctic in June, 1931

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

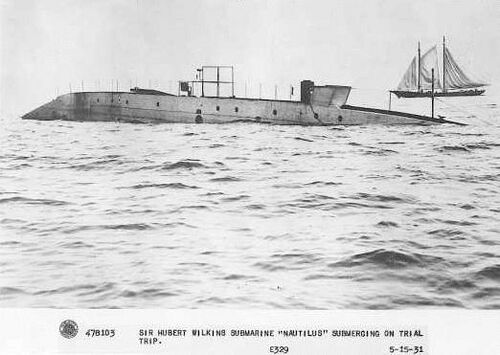

A photo of the ex-O-12, now renamed Nautilus, from the starboard side, submerging on a trial run after the completion of the Arctic conversion work, May 15, 1931. In this view her bow is to the right. Submerged control must have been problematic at best, as Simon Lake had removed the bow diving planes, leaving only the stern planes for angle control. Her conning tower fairwater has been completely removed and an extensive white painted superstructure has been built atop the already existing superstructure. The small topside structures were all retractable or removeable, with the intention being for the Nautilus to slide in under the icepack, running along under the ice like a reverse sled, popping up to the surface when a gap in the pack was encountered.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman

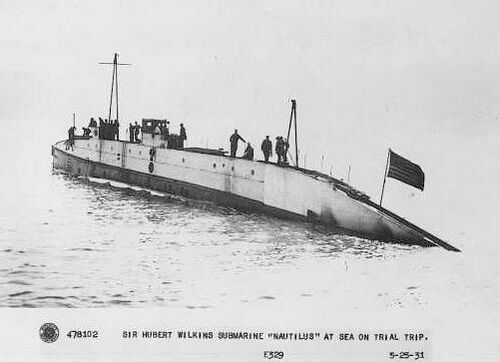

This from the port side shows Nautilus after the completion of the Arctic conversion work, May 25, 1931. She had an all-civilian crew, captained by Sloan Danenhower, a former U.S. Navy officer and associate of Simon Lake. The newly built ice sled superstructure can be seen atop the former main deck line. The superstructure forward contained non-watertight working compartments for scientists and divers, but these compartments could only be used while the boat was surfaced. They had to have been of dubious utility at best.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman

The voyage across the Atlantic

A photo of the crew just before leaving New York City in June 1931 on the first leg of the voyage. From left to right, back row: LT H.W. Ross, USN, Harry Zoelter (oiler), Sir Hubert Wilkins (expedition leader), John A. Janson (oiler), Sloan Danenhower (Captain), H. Rothschild [top] (cook), J. Strohm [below] (machinist), H. Carl Schnetter (engineer), Clarence D. Holland (Asst. Engineer). Left to right, front row: Frank D. Shaw (Chief Engineer), F.A. Blumberg (Chief Electrician), Raymond E. Meyers (radioman), Cornelius P. Royster (electrician), and Edward J. Clark (quartermaster).

Note that this is not the entire crew. Notably missing in this photo is diver Frank Crilley, and the second officer Isaac Schlossbach. It is not known what function LT Ross fulfilled, or whether he made the entire voyage with the boat. Some of these other men did not finish the trip. Some quit after the voyage across the Atlantic, and others were hired in England to make up for the losses.

Photo provided by the late MMCM(SS) Rick Larson, USN (Ret.)

This photo was likely taken during the transit across the Atlantic, June 1931. From left to right is believed to be H. Carl Schnetter, engineer, oiler John A. Janson, and oiler Harry Zoelter. An unidentified man is seen through the doorway at rear of photo. Life looks dirty and grim. One of the many complaints by the crew was that the conversion work left very few places for the crew to sit down, leaving them standing for most of the time they were awake, even while eating. There were not enough bunks for the entire crew, so they were "hot-racking", meaning that when one man went on watch and vacated a bunk, one man going off-watch occupied the bunk.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

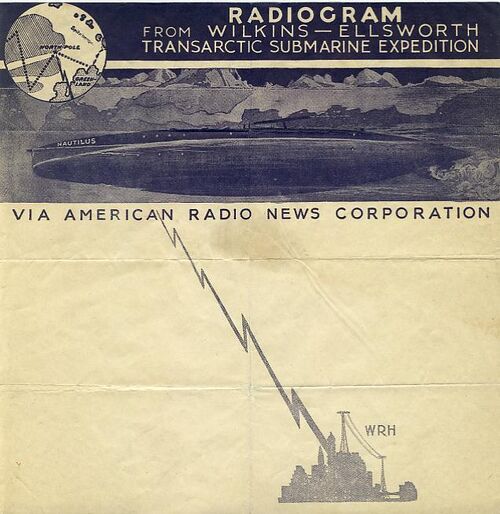

A radiogram form used to Morse code record messages received from the Nautilus during her voyage. One of the many problems facing the expedition was inadequate and poorly maintained radio equipment that failed regularly. Communications with the boat were spotty at best, leaving long periods when nothing was heard from the crew, raising concern.

Image courtesy of James H. Johnson.

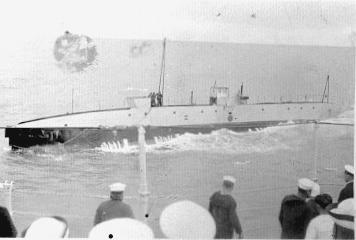

A view of the Nautilus underway at sea in the Atlantic, June 14, 1931, alongside the battleship USS Wyoming (BB-32). The boat was transiting to England on the first leg of her Arctic voyage. Rough seas had battered the small submarine, and both engines had failed leaving her adrift. Danenhower called for help and the Navy came to the rescue. The Wyoming took her under tow to Cork, Ireland.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

The disabled Nautilus under tow from the USS Wyoming (BB-32), June 14. 1931. The boat had been heavily battered by heavy seas and was in rough shape. The deck structure and topside safety lines were in disarray. The submarine's short periscope can be seen protruding up above the deck.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Nautilus in drydock in Devonport, England, June, 1931. The initial tow got her to Cork, Ireland where the situation was assessed. It was found that extensive work was needed to get her into shape so Wilkins arranged for drydock and yard time. She was towed to Devonport in southwestern England where the work was hurriedly done. Time and money was short, so the repairs were not thorough, only the essential jobs were completed and when the boat left for the polar regions she was still in questionable form.

This photo illustrates how the white painted superstructure was built atop the existing deck line. When compared to the last photo on the O-12 page, it can be seen how extensive the conversion work was. Notably, the bow planes have been removed and the slits in the original superstructure plated over, along with the removal of the stockless anchor and its large starboard side recessed housing.

It is important to note that the new superstructure is not watertight. When the boat submerged this area free-flooded. The science and diver working compartments near the small removable bridge would have also flooded, making them of little value upon surfacing in the ice-cold Arctic.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

In the ice pack

A portion of the Nautilus crew on the ice pack, October 11, 1931. They are trying to set up an emergency radio transmitter to get word out to an anxious world that they were still exploring.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Expedition diver Frank Crilley on the bow of the Nautilus overlooking the pancake and pack ice confronting the boat, October 1931. A Navy Reservist, Crilley participated in the Wilkins Expedition in between stints of active duty with the Navy.

Crilley was a Navy diver of great renown. He worked on George Stillson's team that refined and developed the famous Mk 5 diving dress for the Navy. He was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Coolidge for his near super-human efforts during the F-4 salvage operation in 1915. He later participated in the salvage of the submarines USS S-51 (SS-162) in 1925/1926, and the S-4 (SS-109) in 1927/1928. For his work on the S-4 operation he was awarded the Navy Cross.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

On October 11, 1931 the Nautilus put men out on the ice cap for several reasons, one of which was to take a movie of the boat attempting to submerge under the ice. The Nautilus can be seen in the left background, and the camera man on the right, with a rowboat moored at his feet. This was a truly gutsy move on behalf of the camera man, because if the boat encountered difficulty under the ice and sank or became disabled, he would be dead in a few hours. Brave man indeed!

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

After the voyage

Caption from a local newspaper: "Home from the perilous dash---in polar bound submarine. Eleven members of the crew of the Polar-Bound submarine Nautilus. Arriving on the S.S. American Banker today (Monday) following the near fatal culmination of their daring dash through the Arctic Circle. Although the party did not cross the pole, plans are already progressing for another attempt in a more adequately equipped submarine." This photo was likely taken in New York City on October 5, 1931. From left to right front row: Frank D. Shaw, H. Carl Schnetter, Clearance D. Holland, Frank Crilley, and Raymond E. Meyers. Back row, left to right: Harry Zoelter, Raymond Drakio, Cornleius Royster, Vadien Stayrakov, Edward Clark, John A. Janson.

Once again this is not the whole crew, notably Wilkins, Danenhower, and Schlossbach are not present.

Photo contributed by TMC(SS) Donald W. DeCoster, USN (Ret.), now in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

This is a documentary from the Mustard Channel on YouTube. It gives an excellent overview of the Wilkins-Ellsworth Trans-Arctic Expedition and includes some superb CGI graphics of the Nautilus. We can also recommend the other videos on the Mustard Channel, although they mostly cover aviation stories. You won't be disappointed.

Video courtesy of the Mustard Channel on Youtube.

Page created by:

Ric Hedman & David Johnston

1999 - 2023 - PigBoats.COM©

Mountlake Terrace, WA, Norfolk, VA

webmaster@pigboats.com