Wilkins Arctic Submarine Nautilus

Notes

At first, Lake offered Wilkins his old submarine Defender, but Wilkins immediately judged the old boat to be too small for the arduous task. Wilkins and Lake approached the Navy and were able to secure an agreement to lease the decommissioned submarine ex-USS O-12 (SS-73), which was laying in reserve at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. This would be an ideal situation for Lake, as his company had built the O-12 during WWI and he was intimately familiar with her design. The obsolete O-12 was no longer wanted by the Navy so they transferred ownership of the boat to the U.S. Shipping Board, who then agreed to lease the boat back to the newly formed Lake & Danenhower, Inc. for conversion for Wilkins. Former USN submarine commander Sloan Danenhower was now a business associate of Simon Lake, and his expertise got him the job of being the expedition's submarine skipper. The Shipping Board agreed to lease the boat for one dollar for one year, with the only other stipulation being that when the expedition was completed the boat be returned to Navy control or be scuttled in water at least 1,200 feet deep (370 m), so that it could not be used in military operations against the United States.

Lake was granted the rights to use the Philadelphia Navy Yard drydock for the initial conversion work and he used that time to strip the exterior of the boat down to the main deck. He also demilitarized the boat by cutting off the torpedo tubes where they penetrated into the torpedo room. The portions that remained were permanently sealed up with flanges. A diver lock-out chamber was added to the torpedo room, along with a hatch in the bottom to allow the diver to exit and to lower scientific instruments into the water. The rest of the torpedo handling equipment was removed and the remainder of the space turned into a laboratory. The boat's bow was reinforced with concrete and extra steel so that a collision with the ice would not damage it. Other interior refurbishment work was done on the boat, as she had been sitting in reserve for six years and was in bad shape.

She was then towed to the John H. Mathis & Company shipyard in Camden, NJ and eventually to a third yard in Yonkers, NY. where the rest of the conversion work was done. A large ice skid, somewhat like an upside down ski, was built over the main deck and the space underneath it closed in. Other experimental features were added like ice drills that were intended to bore through the ice to bring air to the submerged submarine, a hydraulic spar on the tip of the bow to cushion collisions with the ice, and an extendable skid to provide a shock-absorber effect under the ice. Most of these contraptions were the product of Simon Lake's rather fertile imagination. They were of dubious value and were only barely tested prior to the boat's departure for the Arctic.

In true Simon Lake fashion, the work to convert the boat, now named Nautilus (inspired by Lake's fascination with Jules Verne), took much longer than anticipated and ran considerably over budget. They were pressed for time, as it was the desire of Wilkins and Ellsworth to get the expedition going during the Arctic summer, when conditions were much more favorable. Badly needed work to refurbish the engines, motors, hydraulics, and structure was either rushed through or was entirely deferred. This would prove to be a fateful decision.

The overall design of the conversion work reflected Lake's naivete about Arctic conditions, and his predilection towards a romantic and unrealistic view of the rigors of exploration. The whole concept of the submarine running along under the ice pack on its superstructure skid was based on the false idea that the Arctic ice pack was smooth and flat underneath like that of a frozen freshwater lake. Nothing could be further from the truth. Incredibly, the boat was not equipped with heaters, and the crew suffered terribly from the bone chilling cold that radiated inward from the steel hull. Freshwater in tanks routinely froze solid and there was only one toilet for the entire crew, and that was inconveniently placed between the main engines. The ice drill proved very difficult to use in dockside tests and it failed routinely to bore into test blocks of ice. In the arctic against the rock hard ice found there the drill was completely useless and the trunk leaked through the circumferential seal. For some reason, both the bow and the amidships diving planes had been removed by Lake in Philadelphia, leaving only the stern planes for underwater control, a problematic state of operation at best. The engines failed on the trip across the Atlantic, and they had to be hurriedly overhauled in England before departing for the polar region

Despite the issues, Wilkins pressed on with the expedition, driven by the pressure of his investors and the overbearing influence of Hearst. They made it to the ice pack and even operated under it for short periods. They gathered a lot of useful scientific data, but on an overall basis the expedition was nearly a total failure, with the crew nearly in a mutinous state from the horrid conditions onboard. There were also unsubstantiated reports of deliberate sabotage by the worried crew. The mechanical difficulties encountered by the expedition were more likely due to the poor material condition of the boat and to Lake's contraptions. The expedition ended in a Norwegian fjord near Bergen, where Wilkins and Danenhower lived up to the terms of the contract and scuttled the boat in deep water. It was later discovered and surveyed by Norwegian divers in 1981.

See the photos and video below for a more complete story of the conversion work and the pioneering expedition. Ric has also transcribed a newspaper article from 1931 by Sloan Danenhower that describes the conversion work done to the O-12/Nautilus.

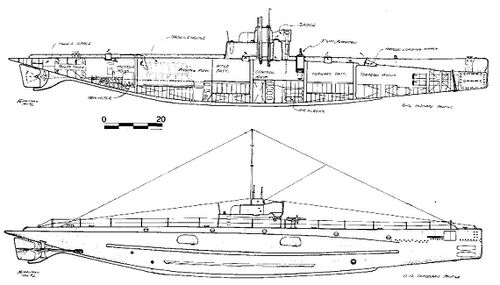

Nautilus configuration drawings

Drawing by Jim Christley, courtesy of U.S. Submarines through 1945 by Norman Friedman.

This drawing shows the O-12 after the completion of the conversion work by Simon Lake. She is now known as Nautilus. Everything above the main deck has been stripped away, even the conning tower. The ice skid superstructure has been built above the main deck, with a new smaller access trunk added where the conning tower was formerly. The structures shown on top of the ice skid can be disassembled and taken below prior to going under the ice. The masts could be lowered into slots in the new superstructure. This would leave a smooth surface for the boat to theoretically glide along under the ice. Note that the bow and amidships diving planes have been removed, leaving only the stern planes for submerged control. This would have made it very difficult to control the boat's depth. This was not considered to be an issue by Lake, as it was intended for the boat to be up against the underside of the ice at all times.

Drawing by Jim Christley, courtesy of U.S. Submarines through 1945 by Norman Friedman.

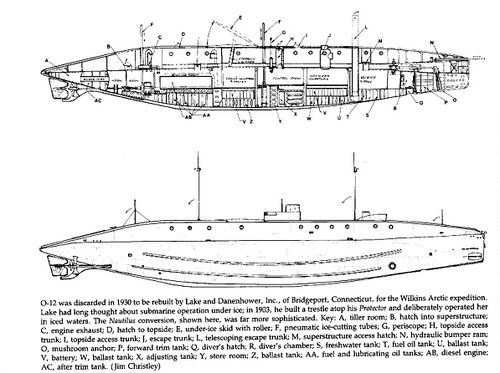

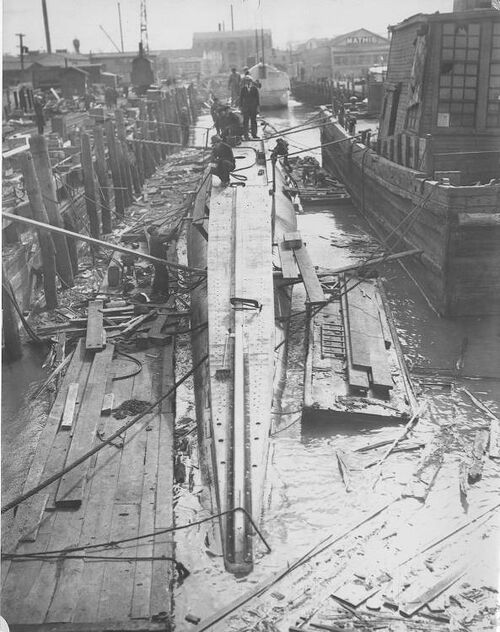

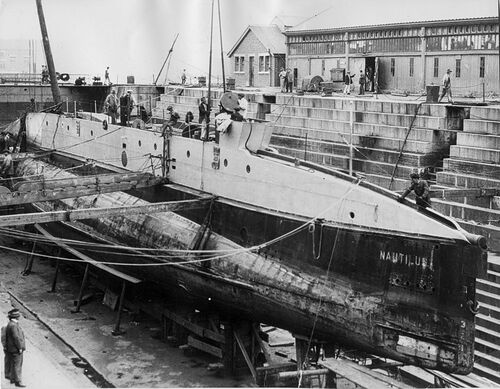

Conversion work and initial sea trials

The former O-12 in drydock at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on December 12, 1930, undergoing conversion for the Wilkins arctic expedition. She would be renamed Nautilus. At this point the Navy ostensibly retained ownership of the boat through the U.S. Shipping Board, with the boat leased her to Lake & Danenhower, Inc. for the expedition. Simon Lake and Sloan Danenhower were allowed to make any modifications necessary to the boat, as it was understood that she would never return to naval service. In this photo Lake employees are working topside, having removed the conning tower fairwater, periscopes, and masts, leaving only the bridge access trunk. An extensive superstructure would be built above the main deck. Her torpedo room was being converted into a diver lockout chamber, a scientific instrument "moon pool", and laboratory. The rest of the boat would get refurbishment as well.

Original photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

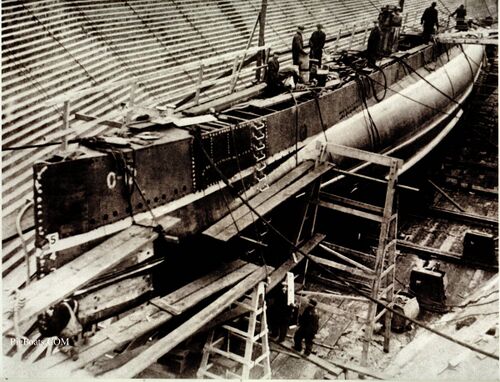

Sir Hubert Wilkins (right) with Simon Lake (middle) and Isaac Schlossbach (left) standing on the starboard rail of the former O-12 during the the first phase of the conversion work in Philadelphia, December 1930. The tall object in the center is the conning tower. The fairwater, bridge, and periscope shears that once surrounded the tower have been completely removed down to the main deck. On these boats the conning tower was little more than an access trunk for the bridge, a little bit bigger than a phone booth. The hatch that would have led to the former bridge can be seen at the top. On the left a rectangular deadlight window can just be seen. The conversion work would remove even this seemingly vital structure, replacing it with a custom made access tube.

Photo courtesy of the Temple University Digital Library.

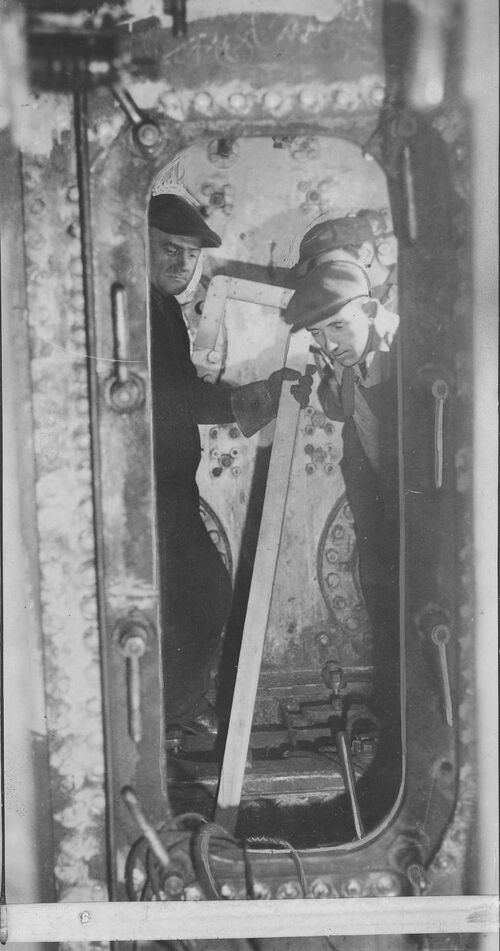

Three workmen inside the former torpedo room, working to complete the conversion of the forward ¼ of the room into a diver lockout chamber. This view is looking forward through the watertight door of a newly installed bulkhead that forms the room. Behind the men is the forward end of the pressure hull, with the flanges for the torpedo tubes just visible. The torpedo tubes had formerly penetrated this bulkhead, passed through several tanks, then had their muzzle ends near the tip of the bow. The tubes themselves have been cut off at the bulkhead and have had blank flanges put in their place.

Photo courtesy of the Temple University Digital Library.

A starboard side photo of the former O-12 under conversion to Wilkin's Nautilus. Here she is alongside at the John H. Mathis & Company shipyard in Camden, NJ in early 1931. After the initial stripping and de-militarization at Philadelphia, the actual Arctic conversion work took place here. This shows the early stage of erecting the framework for the curved ice skid, shown above the temporary wooden safety rails installed along the deck edge. The original conning tower remains at this point, but that would soon be removed for a customized access trunk. Note the floating ice in the water around the sub.

Photo in the private collection of David Johnston.

Conversion work is underway at the Mathis shipyard. The new ice skid has been installed over the main deck. The top of the ice skid now formed a new walking deck. This view is from astern looking forward. Mathis did not run a clean yard. There seems to be an inordinate amount of debris floating in the water.

Photo courtesy of the Temple University Digital Library.

Mathis yard workers attaching siding to the gap area between the Nautilus' ice skid and the former main deck. This gap area was intended to house diver working areas and science laboratories while the boat was surfaced, hence the portholes. It was not watertight and would completely flood when the boat dived, rendering the use of these spaces in the Arctic somewhat suspect. This is reflective of the naivete' of Simon Lake's design for this boat. Much to our surprise, the siding and outer layers were made of wood! The individual planks of the inner layer are clearly seen, and the workman in the center is using a hammer to drive nails.

Photo courtesy of the Temple University Digital Library.

The bow of the Nautilus showing the installation of the hydraulic ice bumper ram. This device would extend out under hydraulic pressure six to eight feet, theoretically providing some cushion in case the Nautilus impacted an ice berg or floe.

Photo courtesy of the Temple University Digital Library.

Men at work inside the Nautilus' engine room, trying to get the rather disheveled Busch-Sulzer 6M85 engines into some sort of shape. Little preservation work had been done on the engines prior to O-12 being placed in reserve status in Philadelphia, and the boat had sat at the yard for six years with no care or maintenance being conducted. The engines were in bad shape and would prove to be the bane of the crew on the trip north.

Photo courtesy of the Temple University Digital Library.

Simon Lake inspecting the operation of the ice drill/extendable access trunk during the conversion work at a shipyard in Yonkers, New York, February, 1931. This was to be an integral part of the equipment for the sub. The drill was to allow the submarine to bore a hole up to the surface and allow the crew to draw in fresh air to breathe and run the diesels to charge batteries. It was also intended to allow the crew to exit the sub and climb on to the ice surface. A temporary frame was erected above the drill that held blocks of ice. Even in this relatively benign test the drill did not work the way Lake intended it to, jamming frequently. With his boundless enthusiasm Lake brushed aside any concerns that Wilkins had concerning the contraption. He continued to tinker with it right up until the submarine departed for the Arctic in June, 1931

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

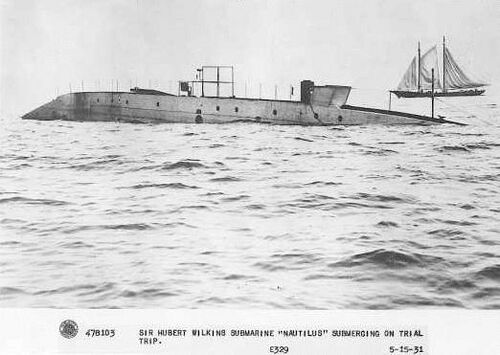

A photo of the ex-O-12, now renamed Nautilus, from the starboard side, submerging on a trial run after the completion of the Arctic conversion work, May 15, 1931. In this view her bow is to the right. Submerged control must have been problematic at best, as Simon Lake had removed the bow diving planes, leaving only the stern planes for angle control. Her conning tower fairwater has been completely removed and an extensive white painted superstructure has been built atop the already existing superstructure. The small topside structures were all retractable or removeable, with the intention being for the Nautilus to slide in under the icepack, running along under the ice like a reverse sled, popping up to the surface when a gap in the pack was encountered.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman

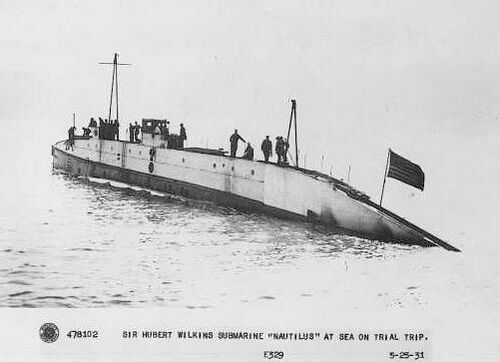

This from the port side shows Nautilus after the completion of the Arctic conversion work, May 25, 1931. She had an all-civilian crew, captained by Sloan Danenhower, a former U.S. Navy officer and associate of Simon Lake. The newly built ice sled superstructure can be seen atop the former main deck line. The superstructure forward contained non-watertight working compartments for scientists and divers, but these compartments could only be used while the boat was surfaced. They had to have been of dubious utility at best.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman

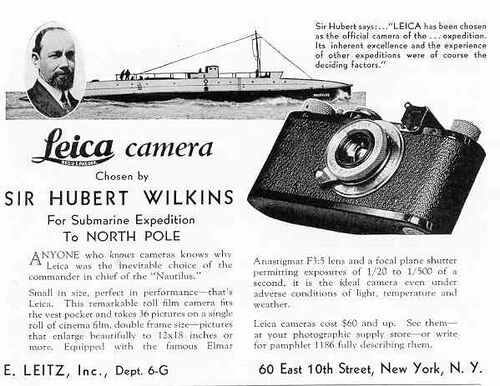

Wilkins and Ellsworth used a variety of methods to raise money for the expedition. A cooperative arrangement with Leica brought in money and also helped to boost sales for the camera manufacturer. The expedition generated a lot of interest amongst the public in many countries.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

A fairly well done video that has some excellent shots of Nautilus during her conversion work and sea trials. There are even some interior shots. The video is partially narrated, but unfortunately the creator chose to use some rather unpleasant organ music in the background, meant to recreate Captain Nemo's playing. There are also a handful of typos in the text. All in all this is a valuable video that shows some very rare shots of this remarkable submarine.

Video from the YouTube smhickel channel.

The voyage across the Atlantic

A photo of the crew just before leaving New York City in June 1931 on the first leg of the voyage. From left to right, back row: LT H.W. Ross, USN, Harry Zoelter (oiler), Sir Hubert Wilkins (expedition leader), John A. Janson (oiler), Sloan Danenhower (Captain), H. Rothschild [top] (cook), J. Strohm [below] (machinist), H. Carl Schnetter (engineer), Clarence D. Holland (Asst. Engineer). Left to right, front row: Frank D. Shaw (Chief Engineer), F.A. Blumberg (Chief Electrician), Raymond E. Meyers (radioman), Cornelius P. Royster (electrician), and Edward J. Clark (quartermaster).

Note that this is not the entire crew. Notably missing in this photo is diver Frank Crilley, and the second officer Isaac Schlossbach. It is not known what function LT Ross fulfilled, or whether he made the entire voyage with the boat. Some of these other men did not finish the trip. Some quit after the voyage across the Atlantic, and others were hired in England to make up for the losses.

Photo provided by the late MMCM(SS) Rick Larson, USN (Ret.)

This photo was likely taken during the transit across the Atlantic, June 1931. This is likely the after battery compartment looking forward. From left to right is believed to be engineer H. Carl Schnetter, oiler John A. Janson, and oiler Harry Zoelter. An unidentified man is seen through the doorway at rear of photo. Life looks dirty and grim. One of the many complaints by the crew was that the conversion work left very few places for the crew to sit down, leaving them standing for most of the time they were awake, even while eating. There were not enough bunks for the entire crew, so they were "hot-racking", meaning that when one man went on watch and vacated a bunk, one man going off-watch occupied the same bunk.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

A radiogram form used to Morse code record messages received from the Nautilus during her voyage. One of the many problems facing the expedition was inadequate and poorly maintained radio equipment that failed regularly. Communications with the boat were spotty at best, leaving long periods when nothing was heard from the crew, raising concern.

Image courtesy of James H. Johnson.

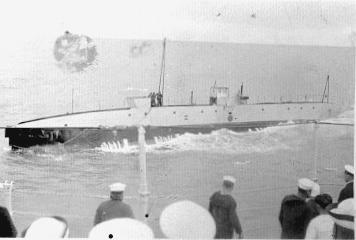

A view of the Nautilus underway at sea in the Atlantic, June 14, 1931, alongside the battleship USS Wyoming (BB-32). The boat was transiting to England on the first leg of her Arctic voyage. Rough seas had battered the small submarine, and both engines had failed leaving her adrift. Danenhower called for help and the Navy came to the rescue. The Wyoming took her under tow to Cork, Ireland.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

The disabled Nautilus under tow by the Wyoming, June 14, 1931. The boat had been heavily battered by heavy seas and was in rough shape. The deck structure and topside safety lines were in disarray. The submarine's short periscope can be seen protruding up above the deck.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Nautilus crewman and cook Harry Rothschild washing up in a Pullman-style washbasin shortly after the arrival in Cork, Ireland, June 1931. This view is in the forward end of the engine room looking forward. The watertight door leading into the after battery/crew's quarters & galley can be seen. On the left, tucked into the space between a frame member, is a Miller-Dunn Style 2 shallow water diving helmet, called a "Divinhood". It was used without a suit or weights and simply rested on the diver's shoulders. It was used for dives in water less than 40 feet. Expedition diver Frank W. Crilley used this helmet for repair and maintenance work in warm waters. For dives in the Arctic he would have used a full diving dress with a closed helmet.

Original photo from the King Features Syndicate, now in the private collection of Ric Hedman and David Johnston.

Nautilus in drydock in Devonport, England, June, 1931. The initial tow got her to Cork, Ireland where the situation was assessed. It was found that extensive work was needed to get her into shape so Wilkins arranged for drydock and yard time. She was towed to Devonport in southwestern England where the work was hurriedly done. Time and money was short, so the repairs were not thorough, only the essential jobs were completed and when the boat left for the polar regions she was still in questionable form.

This photo illustrates how the white painted superstructure was built atop the existing deck line. When compared to the last photo on the O-12 page, it can be seen how extensive the conversion work was. Notably, both the bow and amidships diving planes have been removed and the slits for the bow planes in the original superstructure plated over, along with the removal of the stockless anchor and its large starboard side recessed housing.

It is important to note that the new superstructure is not watertight. When the boat submerged this area free-flooded. The science and diver working compartments near the small removable bridge would have also flooded, making them of little value upon surfacing in the ice-cold Arctic.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

In the ice pack

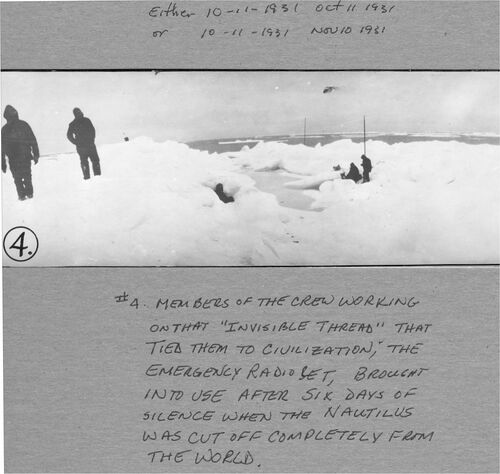

A portion of the Nautilus crew on the ice pack, October 11, 1931. They are trying to set up an emergency radio transmitter to get word out to an anxious world that they were still exploring.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

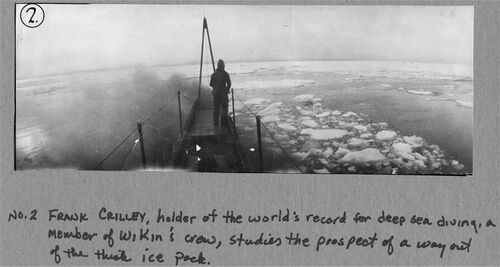

Expedition diver Frank Crilley on the bow of the Nautilus overlooking the pancake and pack ice confronting the boat, October 1931. A Navy Reservist, Crilley participated in the Wilkins Expedition in between stints of active duty with the Navy.

Crilley was a Navy diver of great renown. He worked on George Stillson's team that refined and developed the famous Mk 5 diving dress for the Navy. He was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Coolidge for his near super-human efforts during the F-4 salvage operation in 1915. He later participated in the salvage of the submarines USS S-51 (SS-162) in 1925/1926, and the S-4 (SS-109) in 1927/1928. For his work on the S-4 operation he was awarded the Navy Cross.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

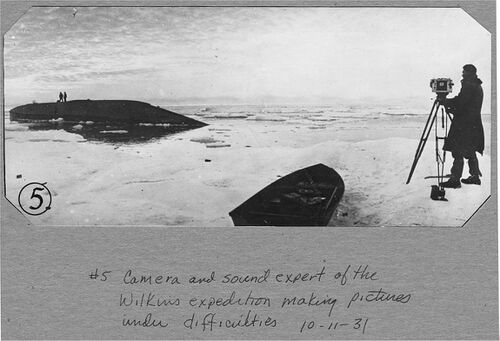

On October 11, 1931 the Nautilus put men out on the ice cap for several reasons, one of which was to take a movie of the boat attempting to submerge under the ice. The Nautilus can be seen in the left background, and the camera man on the right, with a rowboat moored at his feet. This was a truly gutsy move on behalf of the camera man, because if the boat encountered difficulty under the ice and sank or became disabled, he would be dead in a few hours. Brave man indeed!

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

After the voyage

Caption from a local newspaper: "Home from the perilous dash---in polar bound submarine. Eleven members of the crew of the Polar-Bound submarine Nautilus. Arriving on the S.S. American Banker today (Monday) following the near fatal culmination of their daring dash through the Arctic Circle. Although the party did not cross the pole, plans are already progressing for another attempt in a more adequately equipped submarine." This photo was likely taken in New York City on October 5, 1931. From left to right front row: Frank D. Shaw, H. Carl Schnetter, Clearance D. Holland, Frank Crilley, and Raymond E. Meyers. Back row, left to right: Harry Zoelter, Raymond Drakio, Cornleius Royster, Vadien Stayrakov, Edward Clark, John A. Janson.

Once again this is not the whole crew, notably Wilkins, Danenhower, and Schlossbach are not present.

Photo contributed by TMC(SS) Donald W. DeCoster, USN (Ret.), now in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

This is a documentary from the Mustard Channel on YouTube. It gives an excellent overview of the Wilkins-Ellsworth Trans-Arctic Expedition and includes some superb CGI graphics of the Nautilus. We can also recommend the other videos on the Mustard Channel, although they mostly cover aviation stories. You won't be disappointed.

Video courtesy of the Mustard Channel on Youtube.

Page created by:

Ric Hedman & David Johnston

©1999 - 2025 - PigBoats.COM

Mountlake Terrace, WA, Norfolk, VA

webmaster@pigboats.com