Wilkins Arctic Submarine Nautilus: Difference between revisions

Pbcjohnston (talk | contribs) Added photos |

Pbcjohnston (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

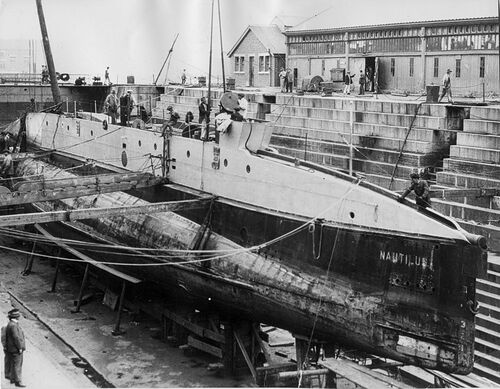

[[File:O-12 Nautilus Conversion.jpg|left|500px]] | [[File:O-12 Nautilus Conversion.jpg|left|500px]] | ||

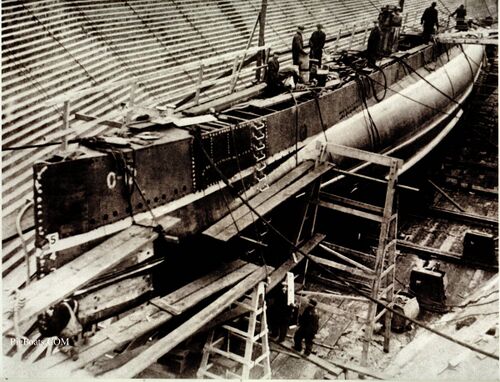

The former O-12 in drydock at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on December 12, 1930, undergoing conversion for the Wilkins arctic expedition. She would be renamed Nautilus. At this point the Navy ostensibly retained ownership of the boat, | The former O-12 in drydock at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on December 12, 1930, undergoing conversion for the Wilkins arctic expedition. She would be renamed Nautilus. At this point the Navy ostensibly retained ownership of the boat through the U.S. Shipping Board, with the boat leased her to Lake & Danenhower, Inc. for the expedition. Simon Lake and Sloan Danenhower were allowed to make any modifications necessary to the boat, as it was understood that she would never return to naval service. In this photo Lake employees are working topside, having removed the conning tower fairwater, periscopes, and masts, leaving only the bridge access trunk. An extensive superstructure would be built above the main deck. Her torpedo room was being converted into a diver lockout chamber, a scientific instrument "moon pool", and laboratory. The rest of the boat would get refurbishment as well. | ||

<small>Original photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.</small> | <small>Original photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.</small> | ||

Revision as of 19:45, 21 April 2024

Notes

At first, Lake offered Wilkins his old submarine Defender, but Wilkins immediately judged the old boat to be too small for the arduous task. Wilkins and Lake approached the Navy and were able to secure an agreement to lease the decommissioned submarine ex-USS O-12 (SS-73), which was laying in reserve at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. This would be an ideal situation for Lake, as his company had built the O-12 during WWI and he was intimately familiar with her design. The obsolete O-12 was no longer wanted by the Navy so they transferred ownership of the boat to the U.S. Shipping Board, who then agreed to lease the boat back to the newly formed Lake & Danenhower, Inc. for conversion for Wilkins. Former USN submarine commander Sloan Danenhower was now a business associate of Simon Lake, and his expertise got him the job of being the expedition's submarine skipper. The Shipping Board agreed to lease the boat for one dollar for one year, with the only other stipulation being that when the expedition was completed that the boat be returned to Navy control or be scuttled in water at least 1,200 feet deep (370 m), so that it could not be used in military operations against the United States.

Lake was granted the rights to use the Philadelphia Navy Yard drydock for the initial conversion work and he used that time to strip the exterior of the boat down to the main deck. He also demilitarized the boat by cutting off the torpedo tubes where they penetrated into the torpedo room. The portions that remained were permanently sealed up with flanges. A diver lock-out chamber was added to the torpedo room, along with a hatch in the bottom to allow the diver to exit and to lower scientific instruments into the water. The rest of the torpedo handling equipment was removed and the remainder of the space turned into a laboratory. The boat's bow was reinforced with concrete and extra steel so that a collision with the ice would not damage it. Other interior refurbishment work was done on the boat, as she had been sitting in reserve for six years and was in bad shape.

She was then towed to the John H. Mathis & Company shipyard in Camden, NJ. where the rest of the conversion work was done. A large ice skid, somewhat like an upside down ski, was built over the main deck and the space underneath in closed in. Other experimental features were added like ice drills that were intended to bore through the ice to bring air to the submerged submarine, a hydraulic spar on the tip of the bow to cushion collisions with the ice, and an extendable skid to provide a shock-absorber effect under the ice. Most of these contraptions were the product of Simon Lake's rather fertile imagination. They were of dubious use and were only barely tested prior to the boat's departure for the Arctic.

In true Simon Lake fashion, the work to convert the boat, now named Nautilus (inspired by Lake's fascination with Jules Verne), took much longer than anticipated and ran considerably over budget. They were pressed for time, as it was the desire of Wilkins and Ellsworth to get the expedition going during the Arctic summer, when conditions were much more favorable. Badly needed work to refurbish the engines, motors, hydraulics, and structure was either rushed through or was entirely deferred. This would prove to be a fateful decision.

The overall design of the conversion work reflected Lake's naivete about Arctic conditions, and his predilection towards a romantic and unrealistic view of the rigors of exploration. For instance, the boat was not equipped with heaters, and the crew suffered terribly from the bone chilling cold that radiated inward from the steel hull. Freshwater in tanks routinely froze solid and there was only one toilet for the entire crew, and that was inconveniently placed between the main engines. The ice drill proved very difficult to use in dockside tests and it failed routinely to bore into test blocks of ice. In the arctic against the rock hard ice found there the drill was completely useless and the trunk leaked through the circumferential seal. For some reason, the bow planes had been removed by Lake in Philadelphia, leaving only the stern planes for underwater control, a problematic state of operation at best. The engines failed on the trip across the Atlantic, and they had to be hurriedly overhauled in England before departing for the polar region

Despite the issues, Wilkins pressed on with the expedition, driven by the pressure of his investors and the overbearing influence of Hearst. They made it to the ice pack and even operated under it for short periods. They gathered much useful scientific data, but on an overall basis the expedition was nearly a total failure, with the crew nearly in an mutinous state from the horrid conditions onboard. The expedition ended in a Norwegian fjord near Bergen, where Wilkins and Danenhower lived up to the terms of the contract and scuttled the boat in deep water. It was later discovered and surveyed by Norwegian divers in 1981.

See the photos and video below for a more complete story of the conversion work and the pioneering expedition. Also see this page for a reprint of an article by Sloan Danenhower describing the conversion work done to the O-12/Nautilus. Special note... the drawings below come from the Syracuse American News Paper, Sunday March 1, 1931 edition. It is likely that the paper has gone out of existence. No mention of it still being in publication could be found anywhere. It may have been absorbed by another paper or just gone out of business as many papers have.

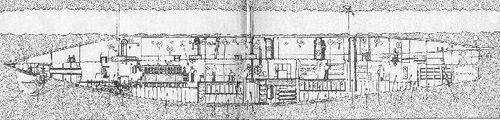

Nautilus configuration drawings

Courtesy of the Syracuse American News Paper, Sunday March 1, 1931 edition.

The former O-12 in drydock at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on December 12, 1930, undergoing conversion for the Wilkins arctic expedition. She would be renamed Nautilus. At this point the Navy ostensibly retained ownership of the boat through the U.S. Shipping Board, with the boat leased her to Lake & Danenhower, Inc. for the expedition. Simon Lake and Sloan Danenhower were allowed to make any modifications necessary to the boat, as it was understood that she would never return to naval service. In this photo Lake employees are working topside, having removed the conning tower fairwater, periscopes, and masts, leaving only the bridge access trunk. An extensive superstructure would be built above the main deck. Her torpedo room was being converted into a diver lockout chamber, a scientific instrument "moon pool", and laboratory. The rest of the boat would get refurbishment as well.

Original photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Simon Lake inspecting the operation of the ice drill/extendable access trunk during the conversion work at a shipyard in Yonkers, New York, February, 1931. This was to be an integral part of the equipment for the sub. The drill was to allow the submarine to bore a hole up to the surface and allow the crew to draw in fresh air to breathe and run the diesels to charge batteries. It was also intended to allow the crew to exit the sub and climb on to the ice surface. A temporary frame was erected above the drill that held blocks of ice. Even in this relatively benign test the drill did not work the way Lake intended it to, jamming frequently. With his boundless enthusiasm Lake brushed aside any concerns that Wilkins had concerning the contraption. He continued to tinker with it right up until the submarine departed for the Arctic in June, 1931

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

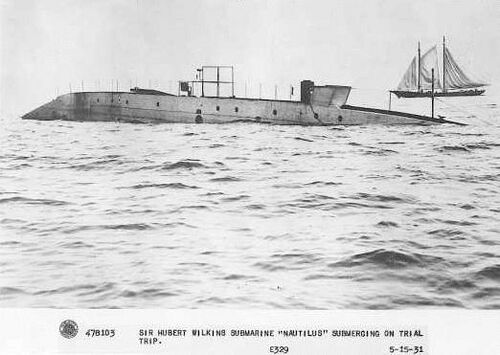

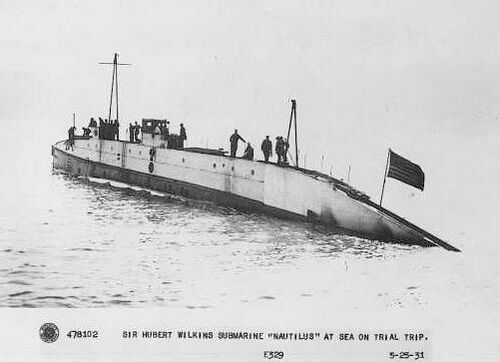

A photo of the ex-O-12, now renamed Nautilus, from the starboard side, submerging on a trial run after the completion of the Arctic conversion work, May 15, 1931. In this view her bow is to the right. Submerged control must have been problematic at best, as Simon Lake had removed the bow diving planes, leaving only the stern planes for angle control. Her conning tower fairwater has been completely removed and an extensive white painted superstructure has been built atop the already existing superstructure. The small topside structures were all retractable or removeable, with the intention being for the Nautilus to slide in under the icepack, running along under the ice like a reverse sled, popping up to the surface when a gap in the pack was encountered.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman

This from the port side shows Nautilus after the completion of the Arctic conversion work, May 25, 1931. She had an all-civilian crew, captained by Sloan Danenhower, a former U.S. Navy officer and associate of Simon Lake. The newly built ice sled superstructure can be seen atop the former main deck line. The superstructure forward contained non-watertight working compartments for scientists and divers, but this compartments could only be used while the boat was surfaced. They had to have been of dubious utility at best.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman

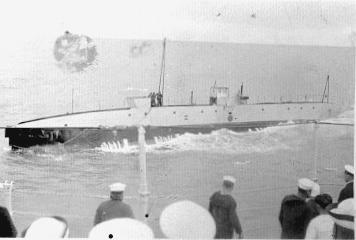

A view of the Nautilus underway at sea in the Atlantic, June 14, 1931, alongside the battleship USS Wyoming (BB-32). The boat was transiting to England on the first leg of her Arctic voyage. Rough seas had battered the small submarine, and both engines had failed leaving her adrift. Danenhower called for help and the Navy came to the rescue. The Wyoming took her under tow to Cork, Ireland.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

The disabled Nautilus under tow from the USS Wyoming (BB-32), June 14. 1931. The boat had been heavily battered by heavy seas and was in rough shape. The deck structure and topside safety lines were in disarray. The submarine's short periscope can be seen protruding up above the deck.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Nautilus in drydock in Devonport, England, June, 1931. The initial tow got her to Cork, Ireland where the situation was assessed. It was found that extensive work was needed to get her into shape so Wilkins arranged for drydock and yard time. She was towed to Devonport in southwestern England where the work was hurriedly done. Time and money was short, so the repairs were not thorough, only the essential jobs were completed and when the boat left for the polar regions she was still in questionable form.

This photo illustrates how the white painted superstructure was built atop the existing deck line. When compared to the last photo on the O-12 page, it can be seen how extensive the conversion work was. Notably, the bow planes have been removed and the slits in the original superstructure plated over, along with the removal of the stockless anchor and its large starboard side recessed housing.

It is important to note that the new superstructure is not watertight. When the boat submerged this area free-flooded. The science and diver working compartments near the small removable bridge would have also flooded, making them of little value upon surfacing in the ice-cold Arctic.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

This is a documentary from the Mustard Channel on YouTube. It gives an excellent overview of the Wilkins-Ellsworth Trans-Arctic Expedition and includes some superb CGI graphics of the O-12 in her conversion guise as the Nautilus. We can also recommend the other videos on the Mustard Channel, although they mostly cover aviation stories. You won't be disappointed.

Video courtesy of the Mustard Channel on Youtube.

Page created by:

Ric Hedman & David Johnston

1999 - 2023 - PigBoats.COM©

Mountlake Terrace, WA, Norfolk, VA

webmaster@pigboats.com