Simon Lake non-Navy Submarines: Difference between revisions

Pbcjohnston (talk | contribs) m (→Protector) |

Pbcjohnston (talk | contribs) m (→Argonaut II) |

||

| (16 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Lake began his life long pursuit of submarine technology in 1894, when he built his first boat, the wooden hulled, slab-sided Argonaut Junior. He followed this up four years later with the much more advanced metal hulled Argonaut 1. During this time he entered into an intense rivalry with his contemporary John P. Holland to design, build, and sell submarines to a newly interested United States Navy. | Lake began his life long pursuit of submarine technology in 1894, when he built his first boat, the wooden hulled, slab-sided Argonaut Junior. He followed this up four years later with the much more advanced metal hulled Argonaut 1. During this time he entered into an intense rivalry with his contemporary John P. Holland to design, build, and sell submarines to a newly interested United States Navy. | ||

Lake was | Lake's vision was for submarines to operate chiefly in an exploration role, fulfilling a military function only as an aside. His operational concept had his submarines sailing on the surface to their operating area, diving to the bottom, then rolling along on wheels to a worksite. Suited divers would then emerge from a hatch in the bottom and perform the boat's mission. His insistence on this operating mode reflected his fascination with Verne, but also betrayed his naivete’ concerning the ease of rolling a submarine along on a bottom that could be littered with boulders or was several feet deep in thick and sticky mud. Using divers as a "weapon" also limited the boat's offensive depth capability, which made the boat vulnerable to counter-attack if detected in shallow water. He was quite stubborn in this vision, and it drove much of his design work. Unfortunately, this concept was not shared by his primary customer, the United States Navy, who understandably saw submarines primarily as a weapon, a mobile minefield upon which an attacking enemy force could be impaled on. Exploration was seen as a secondary role at best. This dichotomy in design philosophy often put Lake and his only real customer at odds with each other. | ||

To aid in his quest to sell submarines to the USN, Lake also developed the idea of submerging a submarine on a level plane, with a zero angle (sometimes called "even keel diving"). Holland used stern mounted diving planes and the power of the propeller to angle the boat downward and push it under, with surfacing being the opposite operation. Lake felt that this was too dangerous. If the crew lost control of the angle the boat could quickly exceed its hull strength depth and be destroyed. He emphasized the use of multiple sets of planes mounted amidships to ease the boat downward while maintaining a zero angle. | To aid in his quest to sell submarines to the USN, Lake also developed the idea of submerging a submarine on a level plane, with a zero angle (sometimes called "even keel diving"). Holland used stern mounted diving planes and the power of the propeller to angle the boat downward and push it under, with surfacing being the opposite operation. Lake felt that this was too dangerous. If the crew lost control of the angle the boat could quickly exceed its hull strength depth and be destroyed. He emphasized the use of multiple sets of planes mounted amidships to ease the boat downward while maintaining a zero angle. While seemingly a great concept on paper, there were too many variables that could not be accounted for at the time. The fore and aft trim had to be perfect, which was very difficult to achieve with the manual ballasting systems of the day. The physics of having your planes to close to the pivot point, the hydrodynamic effects of water on the hull (which acted as its own plane), and the overly complicated control systems designed by Lake all made this maneuver difficult to execute. In many cases a Lake submarine ended up diving with a down angle despite their efforts. The Navy standardized its training on the EB-style angled diving technique, and Lake eventually abandoned zero angle diving. | ||

Although a brilliant engineer, Lake possessed two qualities that tended earn him scorn and mistrust rather than the praise and lucrative USN contracts that he desired. He was quite stubborn in his beliefs about how submarines should be operated, and he refused to tolerate any challenge to those ideals. This stubbornness caused him to be quite outspoken when things did not go his way, earning him a reputation as a pariah. Secondly, despite his acknowledged talent as an engineer, Lake was a poor businessman and organizer. His shipyard was chronically underfunded and poorly managed, and thus his profit margin was quite low, and at times non-existent. Despite numerous attempts, Lake was unable to sell a submarine to the USN until 1912. He had been marginally more successful in the overseas market, but he struggled with the USN until this point. The acceptance of his [[G-1|'''submarine G-1''']] seemed to clear the log-jam for a bit, and over the next 10 years he sold a number of boats to the USN. However, the Navy never really liked his designs. They were mechanically and operationally complex, they had features that the Navy didn't like such as midships diving planes and watertight superstructures | Although a brilliant engineer, Lake possessed two qualities that tended earn him scorn and mistrust rather than the praise and lucrative USN contracts that he desired. He was quite stubborn in his beliefs about how submarines should be operated, and he refused to tolerate any challenge to those ideals. This stubbornness caused him to be quite outspoken when things did not go his way, earning him a reputation as a pariah. Secondly, despite his acknowledged talent as an engineer, Lake was a poor businessman and organizer. His shipyard was chronically underfunded and poorly managed, and thus his profit margin was quite low, and at times non-existent. Despite numerous attempts, Lake was unable to sell a submarine to the USN until 1912. He had been marginally more successful in the overseas market, but he struggled with the USN until this point. The acceptance of his [[G-1|'''submarine G-1''']] seemed to clear the log-jam for a bit, and over the next 10 years he sold a number of boats to the USN. However, the Navy never really liked his designs. They were mechanically and operationally complex, and they had features that the Navy didn't like such as midships diving planes and watertight superstructures. Because of his poor management his boats were usually very late in delivery and lacking in construction quality. He perpetually struggled to make a profit and was often heavily in debt. Finally tired of his business drama, the USN awarded Lake no more contracts after 1922 and his shipyard went out of business for good in 1924. | ||

Lake continued to be a presence in the submarine engineering community, and he was chosen by Sir Hubert Wilkins in 1930 to convert a decommissioned Lake design O-class submarine for an Arctic voyage (see below). Lake's romantic exploration mindset and his Vernian fascination heavily influenced his work on the Arctic submarine, with many of the features and contraptions that he installed being ultimately shown to be impractical or worthless. | Lake continued to be a presence in the submarine engineering community, and he was chosen by Sir Hubert Wilkins in 1930 to convert a [[O-12|'''decommissioned Lake design O-class submarine''']] for an Arctic voyage (see below). Lake's romantic exploration mindset and his Vernian fascination heavily influenced his work on the Arctic submarine, with many of the features and contraptions that he installed being ultimately shown to be impractical or worthless. | ||

This page will highlight some of the submarine work that Simon Lake did that ''was not'' accepted by the United States Navy. These boats, although never commissioned as warships in the USN, still were quite important in advancing the state of the art of submarine design and construction in the United States. The submarines that Lake built that were commissioned by the Navy will have their own pages under the Submarine Classes heading. | This page will highlight some of the submarine work that Simon Lake did that ''was not'' accepted by the United States Navy. These boats, although never commissioned as warships in the USN, still were quite important in advancing the state of the art of submarine design and construction in the United States. The submarines that Lake built that were commissioned by the Navy will have their own pages under the Submarine Classes heading. | ||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

[[File:Lake Argonaut_Junior.jpg|left|500px]] | [[File:Lake Argonaut_Junior.jpg|left|500px|<small>Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.org</small>]] | ||

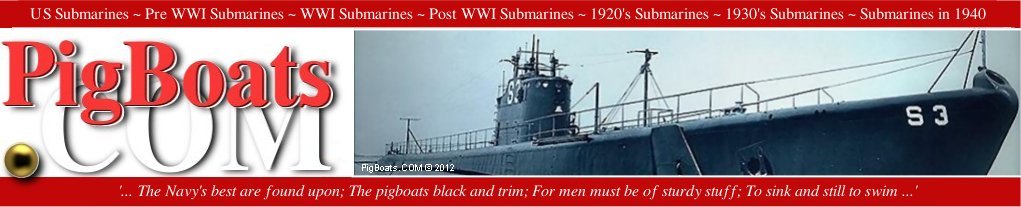

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">This is Simon Lake's first submarine, the wooden and canvas hulled Argonaut Jr. It was 14 feet long with a four foot beam. Built entirely by hand it had two layers of yellow pine boards that sandwiched a rubberized canvas sheath that made it watertight. It had no engine or means of propulsion. It would sink to the bottom and rest on its wheels. Operators inside would hand crank the wheels to move it along the bottom. It also had a diver lock-out chamber. More than anything else it was a proof of concept vessel that gained Lake enough recognition that he was able to secure funding for a much more ambitious follow-on vessel. | <div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">This is Simon Lake's first submarine, the wooden and canvas hulled Argonaut Jr. It was 14 feet long with a four foot beam. Built entirely by hand it had two layers of yellow pine boards that sandwiched a rubberized canvas sheath that made it watertight. It had no engine or means of propulsion. It would sink to the bottom and rest on its wheels. Operators inside would hand crank the wheels to move it along the bottom. It also had a diver lock-out chamber. More than anything else it was a proof of concept vessel that gained Lake enough recognition that he was able to secure funding for a much more ambitious follow-on vessel. | ||

In 2010, an Oklahoma couple built a fully functional replica of the Argonaut Jr. and successfully tested it in a local lake. They did an amazing job for amateurs and their boat looks incredible. For their full story [https://argonautjr.com/ '''go to their website here.'''] | In 2010, an Oklahoma couple built a fully functional replica of the Argonaut Jr. and successfully tested it in a local lake. They did an amazing job for amateurs and their boat looks incredible. For their full story [https://argonautjr.com/ '''go to their website here.'''] | ||

<small>Photo courtesy of | [[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | ||

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#000000"> | |||

=== <big>Argonaut I</big> === | |||

</div> | |||

[[File:Argonaut I on the ways TSIWAP.jpg|left|500px|<small>Photo from the book ''The Submarine in War and Peace'' by Simon Lake, courtesy of Project Gutenberg.</small>]] | |||

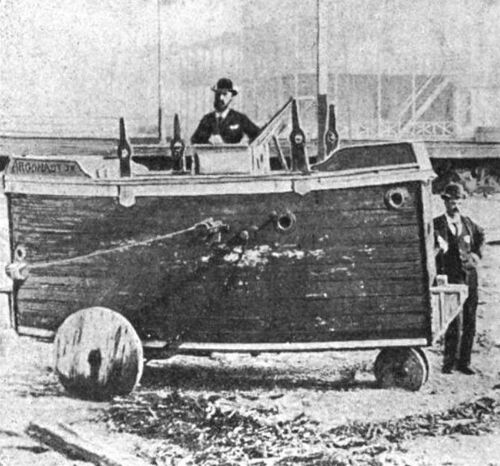

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">Having secured investor funding, Lake built a follow-on vessel that he named simply Argonaut. It was a tremendous advance over the primitive Argonaut Jr. 36 feet long with a 9 foot beam and metal hulled, it was powered by a 30 hp White & Middleton gasoline engine. It also proved to be amazingly seaworthy, racking up over 2,000 miles of surface and submerged running, including an open-ocean transit from Cape May to Sandy Hook, NJ. It had wheels for rolling along the bottom and again a diver lockout chamber. From a military standpoint Lake marketed it as being able to stealthily enter a minefield, send a diver out, and cut mine cables. The same diver would also be able to gather intelligence on other underwater defenses and conduct salvage work. It had no other offensive capability. | |||

This photo shows Argonaut I on the building ways at the Columbian Iron Works, summer of 1896. The facility was at Locust Point, near Fort McHenry, in Baltimore, Maryland. The large forward wheels and view ports at the bow are very apparent. Just below the forward view ports and between the wooden cribbing would be the diver's hatch. | |||

[[Argonaut 1|See more Argonaut I photos]] | |||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | [[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | ||

| Line 36: | Line 48: | ||

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#000000"> | <div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#000000"> | ||

=== <big>Argonaut | === <big>Argonaut II</big> === | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

[[File: | [[File:Argonaut II.jpg|left|500px|Photo from the old simonlake.com site, now on the Internet Archive]] | ||

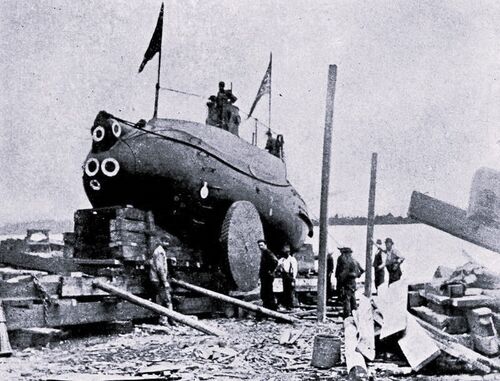

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B"> | <div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">Lake quickly realized the limitations of the original Argonaut design. In late 1898 he took the boat in hand for extensive modifications. Significantly, he lengthened the boat by 24 feet, and installed a much more powerful 60 hp White & Middleton engine, with a smaller four hp auxiliary engine as a supplement. With the idea that the boat would be routinely capable of off shore operations he also completely rebuilt the superstructure topside, giving it a rounded schooner shape. This superstructure would make the boat far more seaworthy while surfaced, but would be free-flooding while submerged. The two large front wheels were reduced in size (not yet installed in this view) and a pressure proof searchlight was added to the lower bow. | ||

Renamed Argonaut II, this photo shows the boat in her new guise, hauled out in 1899 near the end of the modification period. This is likely at the J.N. Robins Co. yard in Brooklyn, NY where the conversion work was done, although the background seems to be somewhat suspect. The lengthened rounded pressure hull is visible below the new superstructure. | |||

Note the complete lack of diving planes. Without them it would be very nearly impossible to control the boat while submerged. However, Lake's standard operating procedure was to sail on the surface to his operating area, released anchors from the bottom of the boat, trim it to neutral or slightly negative buoyancy, then pull it down to the bottom. It would then roll along the bottom on its wheels to the work site. | |||

[[Argonaut II|See more Argonaut II photos]] | |||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | [[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | ||

| Line 54: | Line 66: | ||

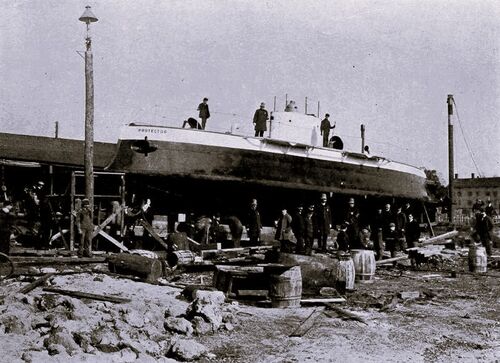

=== <big>Protector</big> === | === <big>Protector</big> === | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

[[File: | [[File:Protector launch TSIWAP.jpg|left|500px|Photo from the book ''The Submarine in War and Peace'' by Simon Lake, courtesy of Project Gutenberg.]] | ||

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">Lake's Protector | <div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">Lake's Protector on the building ways at the Lake yard in Bridgeport, CT., summer 1901. One of her two 18-inch bow torpedo tubes can be seen on the left, with the single stern tube just visible on the right. The two port side midships diving planes are visible at the edge of the superstructure, protected by guards. The large squared conning tower is amidships. This is not a fairwater but the actual pressurized conning tower itself. Not seen in this photo are the two retractable wheels mounted on the keel for bottom running. The lower hatch for the diver's lockout chamber is similarly hidden in this view, on the keel below the bow torpedo tubes.</span> | ||

[[Protector1|See more Protector photos]] | [[Protector1|See more Protector photos]] | ||

| Line 68: | Line 78: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

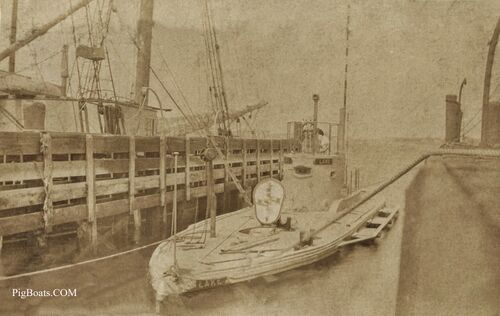

[[File:The Lake docked Remastered 2A.jpg|left|500px|Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman. MAY NOT be reproduced without permission.]] | [[File:The Lake docked Remastered 2A.jpg|left|500px|Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman. MAY NOT be reproduced without permission.]] | ||

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">After selling Protector to the Russians, Simon Lake headed to Europe for several years, designing and building submarines for Austria and Russia. Lake returned to the states in 1906, goaded into building a submarine for demonstration to the Navy by the 1906 Naval Appropriations Bill that allocated $500,000 in funds for submarines. The result was this submarine, initially called Simon Lake XV, then simply Lake. Entered into the competition against the Electric Boat design [[C-1|'''Octopus (Submarine No. 9)''']], the Lake lost the competition. Refusing to give up Lake rebuilt the boat into a salvage vessel and renamed it Defender. It is a strange tale and the whole story can be [https://pigboats. | <div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">After selling Protector to the Russians, Simon Lake headed to Europe for several years, designing and building submarines for Austria and Russia. Lake returned to the states in 1906, goaded into building a submarine for demonstration to the Navy by the 1906 Naval Appropriations Bill that allocated $500,000 in funds for submarines. The result was this submarine, initially called Simon Lake XV, then simply Lake. Entered into the competition against the Electric Boat design [[C-1|'''Octopus (Submarine No. 9)''']], the Lake lost the competition. Refusing to give up Lake rebuilt the boat into a salvage vessel and renamed it Defender. It is a strange tale and the whole story can be [https://pigboats.com/images/5/5e/Lake_submarine_of_1906.pdf '''read at the article at this link.'''] | ||

This photo shows the Lake moored during the 1906 competition with the Octopus. Her broad, flat deck is quite apparent. Note the unusual oblong torpedo loading hatch and the guard rails protecting the amidships diving planes. She had a helm atop the conning tower and a type of a periscope that Simon Lake called an "omniscope". | This photo shows the Lake moored during the 1906 competition with the Octopus. Her broad, flat deck is quite apparent. Note the unusual oblong torpedo loading hatch and the guard rails protecting the amidships diving planes. She had a helm atop the conning tower and a type of a periscope that Simon Lake called an "omniscope". | ||

Revision as of 19:55, 28 August 2024

A brief history of Simon Lake

Lake began his life long pursuit of submarine technology in 1894, when he built his first boat, the wooden hulled, slab-sided Argonaut Junior. He followed this up four years later with the much more advanced metal hulled Argonaut 1. During this time he entered into an intense rivalry with his contemporary John P. Holland to design, build, and sell submarines to a newly interested United States Navy.

Lake's vision was for submarines to operate chiefly in an exploration role, fulfilling a military function only as an aside. His operational concept had his submarines sailing on the surface to their operating area, diving to the bottom, then rolling along on wheels to a worksite. Suited divers would then emerge from a hatch in the bottom and perform the boat's mission. His insistence on this operating mode reflected his fascination with Verne, but also betrayed his naivete’ concerning the ease of rolling a submarine along on a bottom that could be littered with boulders or was several feet deep in thick and sticky mud. Using divers as a "weapon" also limited the boat's offensive depth capability, which made the boat vulnerable to counter-attack if detected in shallow water. He was quite stubborn in this vision, and it drove much of his design work. Unfortunately, this concept was not shared by his primary customer, the United States Navy, who understandably saw submarines primarily as a weapon, a mobile minefield upon which an attacking enemy force could be impaled on. Exploration was seen as a secondary role at best. This dichotomy in design philosophy often put Lake and his only real customer at odds with each other.

To aid in his quest to sell submarines to the USN, Lake also developed the idea of submerging a submarine on a level plane, with a zero angle (sometimes called "even keel diving"). Holland used stern mounted diving planes and the power of the propeller to angle the boat downward and push it under, with surfacing being the opposite operation. Lake felt that this was too dangerous. If the crew lost control of the angle the boat could quickly exceed its hull strength depth and be destroyed. He emphasized the use of multiple sets of planes mounted amidships to ease the boat downward while maintaining a zero angle. While seemingly a great concept on paper, there were too many variables that could not be accounted for at the time. The fore and aft trim had to be perfect, which was very difficult to achieve with the manual ballasting systems of the day. The physics of having your planes to close to the pivot point, the hydrodynamic effects of water on the hull (which acted as its own plane), and the overly complicated control systems designed by Lake all made this maneuver difficult to execute. In many cases a Lake submarine ended up diving with a down angle despite their efforts. The Navy standardized its training on the EB-style angled diving technique, and Lake eventually abandoned zero angle diving.

Although a brilliant engineer, Lake possessed two qualities that tended earn him scorn and mistrust rather than the praise and lucrative USN contracts that he desired. He was quite stubborn in his beliefs about how submarines should be operated, and he refused to tolerate any challenge to those ideals. This stubbornness caused him to be quite outspoken when things did not go his way, earning him a reputation as a pariah. Secondly, despite his acknowledged talent as an engineer, Lake was a poor businessman and organizer. His shipyard was chronically underfunded and poorly managed, and thus his profit margin was quite low, and at times non-existent. Despite numerous attempts, Lake was unable to sell a submarine to the USN until 1912. He had been marginally more successful in the overseas market, but he struggled with the USN until this point. The acceptance of his submarine G-1 seemed to clear the log-jam for a bit, and over the next 10 years he sold a number of boats to the USN. However, the Navy never really liked his designs. They were mechanically and operationally complex, and they had features that the Navy didn't like such as midships diving planes and watertight superstructures. Because of his poor management his boats were usually very late in delivery and lacking in construction quality. He perpetually struggled to make a profit and was often heavily in debt. Finally tired of his business drama, the USN awarded Lake no more contracts after 1922 and his shipyard went out of business for good in 1924.

Lake continued to be a presence in the submarine engineering community, and he was chosen by Sir Hubert Wilkins in 1930 to convert a decommissioned Lake design O-class submarine for an Arctic voyage (see below). Lake's romantic exploration mindset and his Vernian fascination heavily influenced his work on the Arctic submarine, with many of the features and contraptions that he installed being ultimately shown to be impractical or worthless.

This page will highlight some of the submarine work that Simon Lake did that was not accepted by the United States Navy. These boats, although never commissioned as warships in the USN, still were quite important in advancing the state of the art of submarine design and construction in the United States. The submarines that Lake built that were commissioned by the Navy will have their own pages under the Submarine Classes heading.

Argonaut Junior

In 2010, an Oklahoma couple built a fully functional replica of the Argonaut Jr. and successfully tested it in a local lake. They did an amazing job for amateurs and their boat looks incredible. For their full story go to their website here.

Argonaut I

This photo shows Argonaut I on the building ways at the Columbian Iron Works, summer of 1896. The facility was at Locust Point, near Fort McHenry, in Baltimore, Maryland. The large forward wheels and view ports at the bow are very apparent. Just below the forward view ports and between the wooden cribbing would be the diver's hatch.

Argonaut II

Renamed Argonaut II, this photo shows the boat in her new guise, hauled out in 1899 near the end of the modification period. This is likely at the J.N. Robins Co. yard in Brooklyn, NY where the conversion work was done, although the background seems to be somewhat suspect. The lengthened rounded pressure hull is visible below the new superstructure.

Note the complete lack of diving planes. Without them it would be very nearly impossible to control the boat while submerged. However, Lake's standard operating procedure was to sail on the surface to his operating area, released anchors from the bottom of the boat, trim it to neutral or slightly negative buoyancy, then pull it down to the bottom. It would then roll along the bottom on its wheels to the work site.

Protector

Simon Lake XV/Lake/Defender

This photo shows the Lake moored during the 1906 competition with the Octopus. Her broad, flat deck is quite apparent. Note the unusual oblong torpedo loading hatch and the guard rails protecting the amidships diving planes. She had a helm atop the conning tower and a type of a periscope that Simon Lake called an "omniscope".

This is a very rare photo that is exclusive to PigBoats.COM. Originally it was a postcard that was acquired by Ric Hedman. It had black postal marks on it that partially obscured the image. After being scanned electronically it was painstakingly restored by PigBoats associate Matthew Tripp. The result is an unique look into American submarine history.

Wilkins Arctic Submarine Nautilus (1931)

PigBoats.COM has a collection of drawings and photographs of the boat and the men who sailed her to the Arctic, along with a link to an excellent video that covers the expedition in depth. Those can be found here. In addition, Ric has recreated verbatim a newspaper article written by Sloan Danenhower in March 1931 that describes the technical aspects of the Nautilus and their plans for the voyage.

Explorer

Page created by:

Ric Hedman & David Johnston

1999 - 2023 - PigBoats.COM©

Mountlake Terrace, WA, Norfolk, VA

webmaster@pigboats.com