John P. Holland biography and submarines

The early years

In fact, John did not speak any English until he attended the St. Macreehy's National School just down the street from the house in Liscannor. John proved to be a capable student, but struggled with serious health issues, including poor eyesight. His family survived the Great Famine in Ireland relatively intact only because his father's employment gave them a relatively clean and well maintained house. John witnessed the depredations of the Great Famine firsthand, and the British government's lack of response instilled in him a deeply seated animosity towards the British.

John took to his studies with vigor and by 1853 his family moved to Limerick with John attending the Christian Brothers School there. By age 17 he joined the brotherhood and was given the Christian name Philip, which he retained as his middle name for the rest of his life. He was soon accepted as a teacher. During this period he fell under the influence of Brother James Dominic Burke, a renowned man of science. John took to the science studies with gusto, displaying a tremendous mechanical aptitude. Brother Burke was conducting experiments in underwater propulsion using electricity and the firing of torpedoes against ships in a model basin. These activities struck a spark in John, and he began his lifelong fascination with submarines.

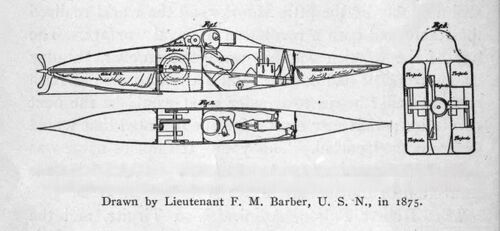

When exactly he designed his first submarine is somewhat up for debate, but it is quite likely that he made his first sketches during the period of 1858-1872, as he moved in and out of various Christian Brothers sponsored teaching positions while dealing with several health issues. Although this sketch here comes from a later interpretation, this is essentially the first design from the fertile mind of John P. Holland. As you can see here this was a human powered affair, with a recumbent seated operator wearing a diving suit. Ballast controls were between the operator's legs as he pushed two treadles that were mechanically linked to the propeller shaft. The boat was rectangular in cross section, with four detachable "torpedoes" (i.e. mines) in a compartment behind the operator. This design was never built, as even John could recognize its limitations. In some texts it is referred to as the "Holland I" design, although Holland himself never referred to it in this fashion.

1872 would prove to be a watershed year in the life of John P. Holland. That year he became involved in an effort sponsored by subset of the Christian Brothers that campaigned for better and more efficient schools. This effort angered the bulk of the group, who saw it as an affront to their teaching philosophy. John was also continuously battling health issues, and these stresses caused him to decline perpetual vows with the order at Christmas 1872. His father had passed away many years earlier, and his elderly mother and brother Michael had emigrated to the U.S. He decided to join them and set sail for a new life in the states on May 26, 1873. He spent the summer and fall in Liverpool while he awaited further passage, finally landing in Boston in November, 1873. Nearly broke when he landed, one of the few possessions that he had upon arrival were the drawings of his initial submarine design.

He no sooner landed in a wintery Boston when he slipped and fell on an icy street. He broke a leg, and spent the next three months laid up in bed as he healed. He used the time to go back and reconsider his submarine designs, refining them and improving the drawings. John landed a job at the St. John's Parochial School in Paterson, NJ and began working in earnest on his submarine ideas in his spare time. After consulting with a friend in 1875, he submitted the initial pedal powered design to the Navy Department. The Navy utterly rejected Holland's work, with the Secretary calling it "a fantastic scheme of a civilian landsman."

It was at this time that his brother Michael introduced him to members of the Fenian Brotherhood, an American based society of Irish expatriates whose goal was the overthrow of British influence and control in Ireland. The Fenians did not shy away from violence as a means to an end, and Holland's technical expertise and fervent belief in a free Ireland impressed the Fenian leadership. They saw his concepts as a means of hitting back at the British Royal Navy.

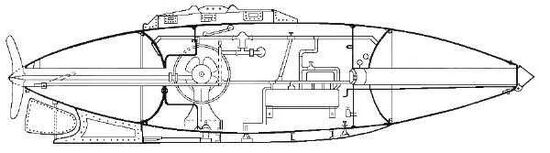

Holland I

The Brayton kerosine engine was the only means of propulsion. There was no battery or electric motor for submerged propulsion. Compressed air tanks fore and aft supplied air for the engine, breathing, and blowing ballast tanks. Exhaust from the engine was vented overboard. Using less air than a modern lawnmower gasoline engine, running the Brayton engine while submerged was at least practical, if not incredibly dangerous due to fumes, heat, and noise. Even still its use would have resulted in a very limited underwater endurance, as rather soon you would simply run out of air with the engine using the bulk of what was stored.

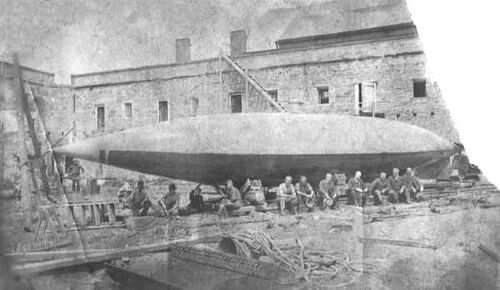

On May 22, 1878 the boat was ready. It was loaded onto a horse-drawn wagon and taken down to the Upper Passaic River in Paterson. Launched into the river with a crowd of onlookers lining the banks, Holland himself entered the boat and attempted to get the balky Brayton engine running. Accounts differ as to whether he was successful in that particular task. Some say that he needed the extra heat of a shore based steam engine to get the engine running, with another account stating a steam line was run to the sub from another boat and it stayed attached during the trial run in the river with the steam boat following on the surface. At any rate, Holland was successful in running the boat up and down the river, submerging to a depth of 12 feet. It was even reported that he stayed submerged for quite a while in an endurance test, likely with the Brayton engine stopped to preserve air. Holland's notes recorded after the test indicated that he was satisfied with the performance of the Holland I overall, but he noted that the midships mounted diving planes were ineffective due to the fact that they were mounted near the center of gravity of the boat and thus had little effect in controlling depth or angle. He resolved to move them aft in later boats.

Members of the Fenian Brotherhood were present for the test and they were very pleased. They immediately offered to finance a follow-on boat. The Holland I was stripped of useful equipment by Holland, and he deliberately scuttled the boat in the Passaic River near the Spruce Street bridge. A short time later some local men salvaged the conning tower for scrap, but in 1927 the entire boat was raised from the mud and donated to the Paterson Museum. The photo above is a recent shot of the boat as it currently sits in the museum after restoration work and receiving a replacement conning tower.

Holland II (aka "Fenian Ram") & Holland III

Once again Holland turned to the Brayton engine for motive power despite the troubles he had with it earlier, mostly because in 1878 it was the only practical internal combustion engine available. Holland extensively modified the engine with an eye towards improving efficiency. It was a two cylinder, 17 horsepower engine and was sited on the starboard side of the boat's only compartment. Once again the exhaust from the engine was continuously vented overboard, this time assisted by a check valve that prevented water from entering. An air compressor ran down the port side and was powered off the Brayton engine. A large flywheel that assisted in keeping consistent propeller shaft revolutions sat on the port side. Large ballast tanks surrounded the propeller shaft aft and the single 9-inch diameter "torpedo tube" forward. The operator sat in a seat at the aft end of the compartment with his head up in the small conning tower. An engineer worked the engine, the compressor, and ballast controls. A gunner was responsible for firing the tube. The tube was closed with a breech door inside the boat, and with a pointed cap on the muzzle end at the tip of the bow.

-

View from forward looking aft at the operator seat and flywheel, with the Brayton engine on the left.

-

The Brayton engine on the starboard side.

-

The air compressor on the port side.

Photos via Wikimedia Commons.

The boat, now dubbed the "Fenian Ram" by a reporter who thought it would ram ships, was ready for testing in 1881. Holland made a series of short shakedown cruises in the Hudson River through 1881 and 1882, gathering data on performance and tweaking the design. By 1883 he was running extended cruises in the Hudson River and The Narrows off Brooklyn and Staten Island. The Fenian Ram showed itself to be a remarkable boat. The tests were well covered by the press and the fact that the boat had been financed by Fenian revolutionaries was essentially an open secret. Holland was able to control it easily both surfaced and submerged and could routinely run submerged at depths up to 50 feet. It was also reported that Holland could spend "several hours" submerged in the boat, undoubtedly with the Brayton engine secured to preserve air. In one test of the pneumatic tube an Ericsson dummy projectile was fired with the tube muzzle about three feet below the water. 300 psi of air pressure forced the projectile out of the tube eight to ten feet before it broke the surface and rose "sixty to seventy feet in the air" before it reentered the water, burying itself in the river mud. Historian Lawrence Goldstone called the Ram "the most advanced submarine in the world at that time". He was correct. Despite the success of the Fenian Ram, the response from the U.S. Navy was nothing more than a disinterested yawn.

Holland, ever the inveterate tinkerer, was never fully satisfied with the Ram's performance. He convinced the Fenians to finance a sub-scale duplicate of the boat so that he could test new ideas without having to modify the Ram before the concepts were proven. The new boat was outwardly quite similar to the Fenian Ram, but only 14 feet long with a single operator and a one ton displacement. Holland named this boat the Holland III. Unfortunately no photographs of the Holland III exist. Testing of the smaller boat ran in parallel with the Fenian Ram.

The Fenians proved themselves to be surprisingly inept, both as terrorists and as financiers. Strong and forceful personalities with little to no organizational skill fractured the society's plans, and graft and corruption squandered the money they had raised. By the fall of 1883 the society was broke, and the members of the leadership hatched a plan to recover a portion of the nearly $60,000 (over $2,000,000 in 2024 dollars) they had invested in the Fenian Ram. In November, 1883, late at night, a group led by Fenian leader John Breslin used a permission slip with Holland's forged signature to gain access to the Fenian Ram and the Holland III at their slip on the Hudson River. Using a tugboat they towed both boats away, intending to spirit them to a yard in New Haven, CT where they could be sold off. Unfortunately, they neglected to secure the hatch on the Holland III and the small boat was swamped and sank under tow in the East River.

The motley force managed to make it to New Haven where apparently Breslin had a change of heart about selling off the Fenian Ram. He and a group of men attempted to operate the boat in Long Island Sound, but found they didn't understand how to operate the boat's systems without Holland. In a move laden with unmitigated audacity, Breslin then contacted Holland and asked him to help with the operation of the boat that they had just stolen from him. Holland, thoroughly disgusted and disillusioned with the inept shenanigans of the Fenians, steadfastly refused and washed his hands of the whole affair.

Breslin and his cohorts, unable to operate or sell the boat had it hauled out of the water and stored in a woodshed off the Mill River in New Haven. There it sat until 1916 when Irish sympathizers moved it to Madison Square Garden in New York City and put it on display to raise money for the victims of the Easter Rising. After serving its purpose there it was moved to the grounds of the New York State Marine School where it stayed until 1927. It was purchased and moved to West Side Park in Paterson. Note in the photo at left that the boat is missing the pointed bow cap for the torpedo tube. It stayed there displayed outside in the elements until 2001 when it was acquired by the Paterson Museum and moved indoors, where it went through a preservation process that allows visitors to view it to this day. It sits directly adjacent to its predecessor the Holland I. The photo on the right gives a good view of the stern diving planes, with one of the propeller blades showing signs of damage. The rudder is also suffering from corrosion damage.

Holland IV (aka "The Zalinski Boat")

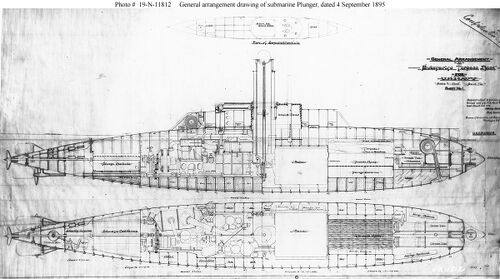

Holland V (Plunger 1895)

The Electric Boat era and Holland's later years

Page created by:

Ric Hedman & David Johnston

1999 - 2023 - PigBoats.COM©

Mountlake Terrace, WA, Norfolk, VA

webmaster@pigboats.com