F-4 salvage

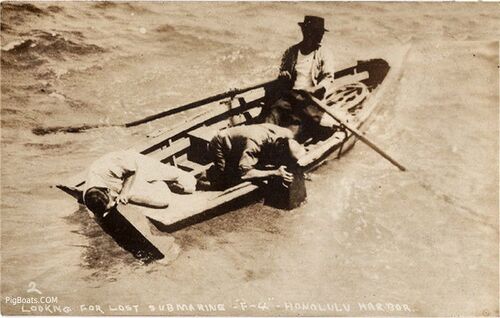

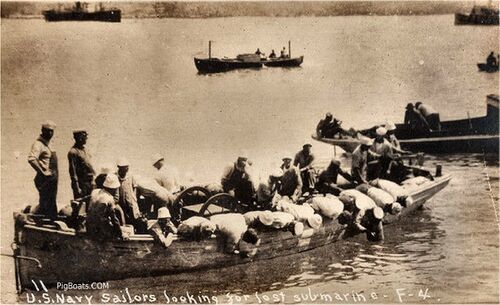

Search for the Lost Boat

Here two men are using a box with a glass plate in the bottom that allowed a clearer view of things underwater.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

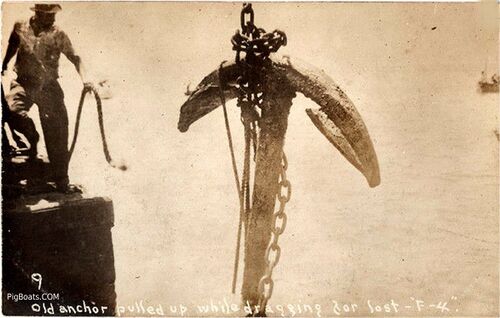

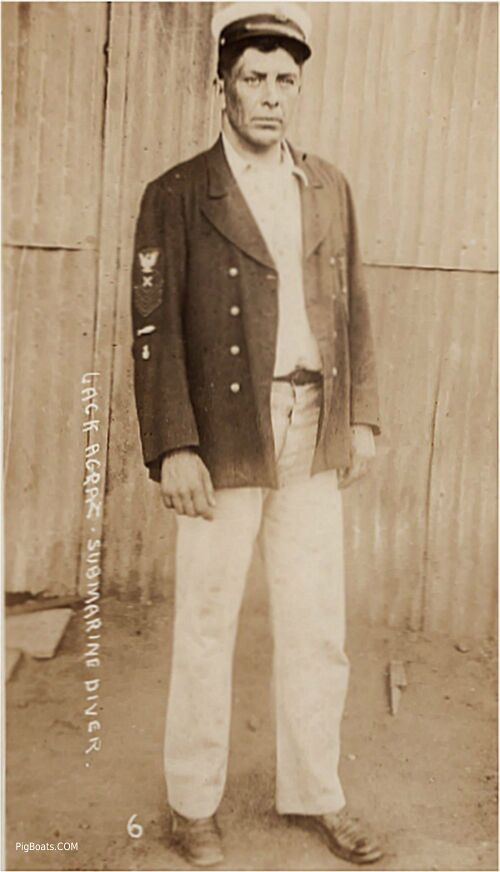

According to the Board of Investigation Report, when the anchor was discovered Jack Agraz, Chief Gunners Mate, a Navy diver from the USS F-1, donned his gear and followed the line to the target. Three crews of four men each manned the hand turned air pump supplying air to him. He discovered the grapple chain was wrapped around "an old anchor" at 215 feet. The F-4 had not been found.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

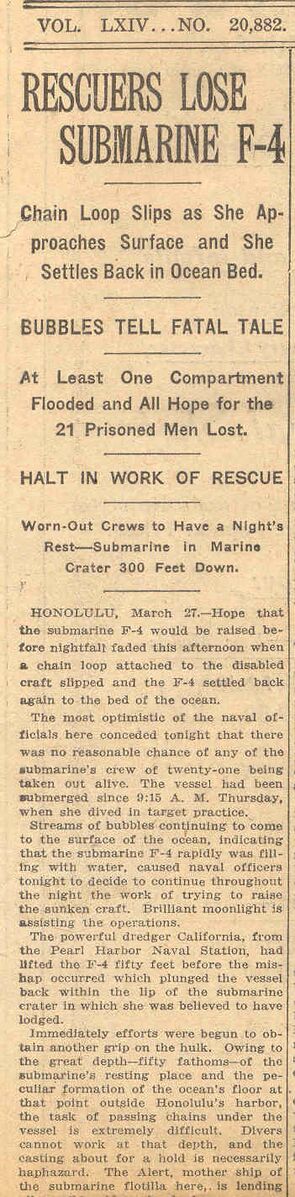

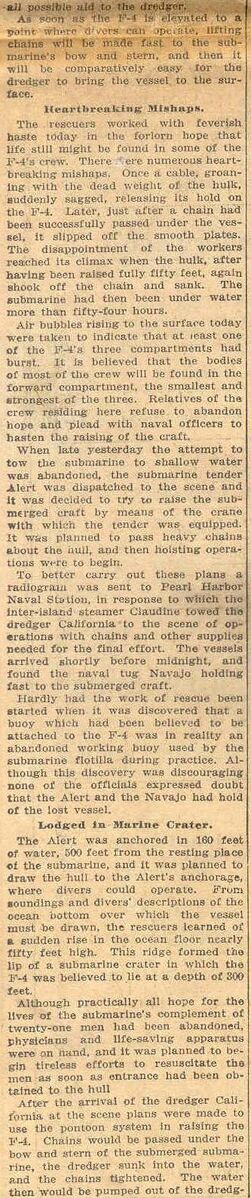

Copyright The New York Times

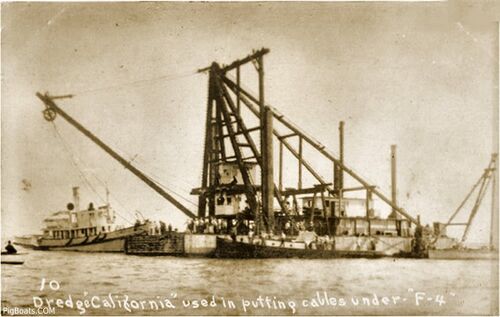

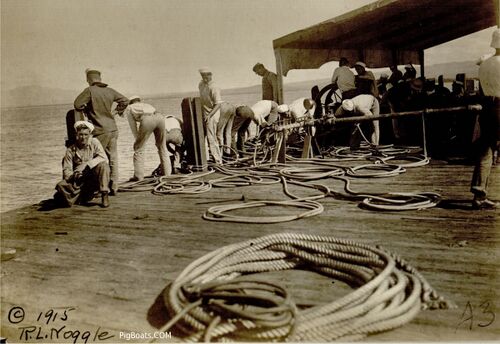

Salvage Work

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

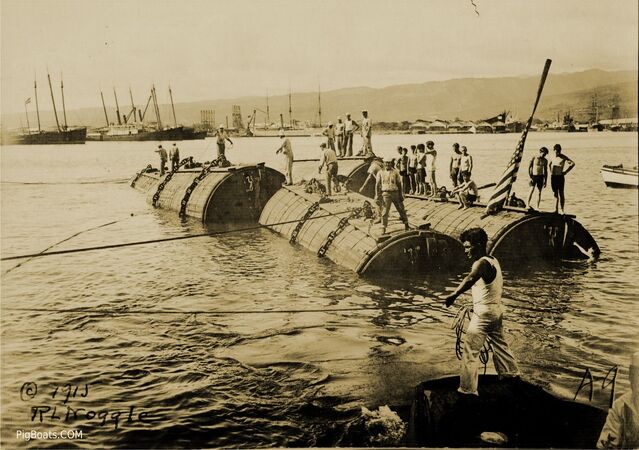

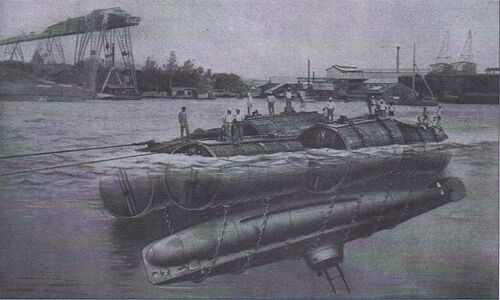

The rope that is being worked on by the men on deck can be seen floating in the water in front of the submarine. There is a similar one stretching from the after deck to what is assumed to be the salvage barge. The F-2 is probably in the process of mooring to that barge to supply the air needed for the pontoons.

Note the proximity to the shore. The F-4 sank just outside of the entrance to Honolulu Harbor, in Mamala Bay. With Oahu essentially being the top of an underwater mountain, the water depth drops off precipitously as soon as you leave the harbor.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

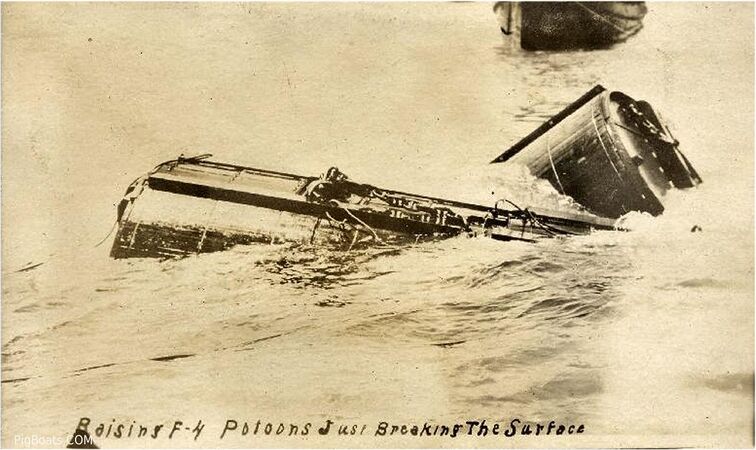

Raising the Boat with Pontoons

Photos in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

In the center background is the Navy floating cantilever pontoon crane YD-25. The crane had a lifting rating of 150 tons. Too little to have lifted the flooded F-4. She was destined to become a visual fixture at Pearl Harbor for the next dozen years.

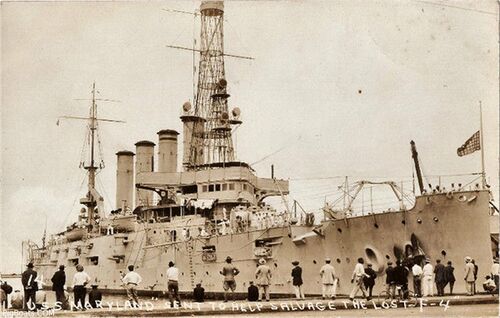

In the left background the USS Maryland is moored. She is the vessel that brought the six lifting pontoons to Hawaii.

Newspaper photo.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo from Beneath the Surface: WWI Submarines Built in Seattle and Vancouver by Bill LIghtfoot.

Photos in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

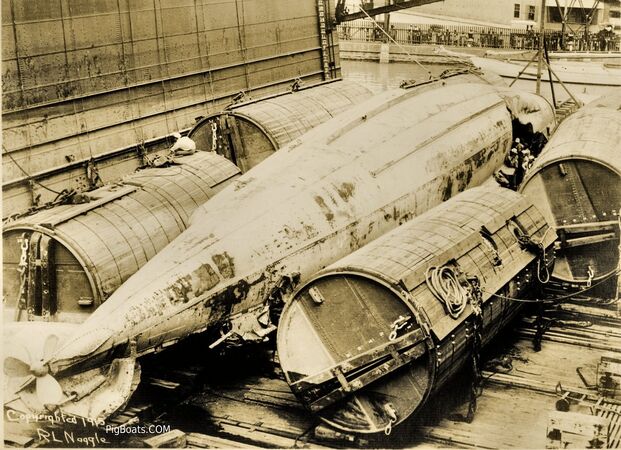

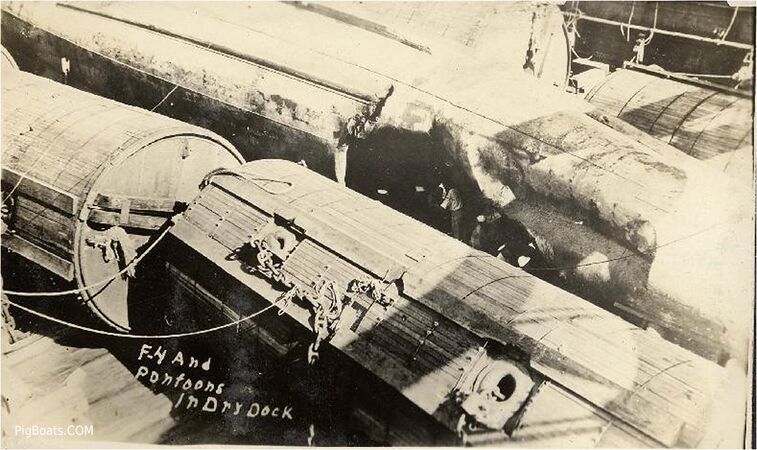

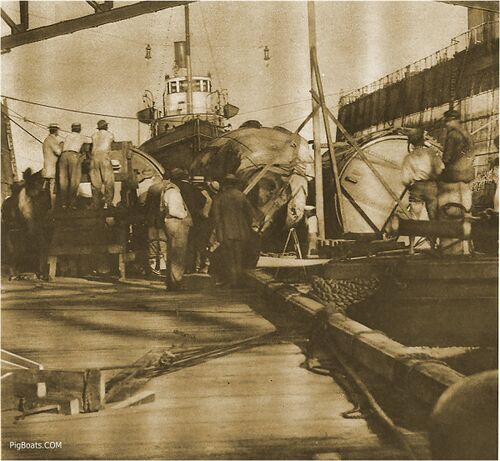

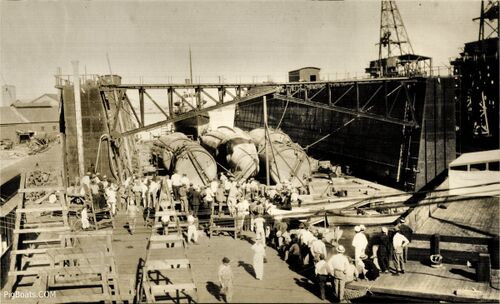

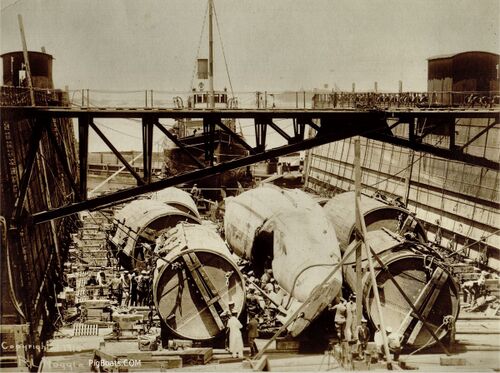

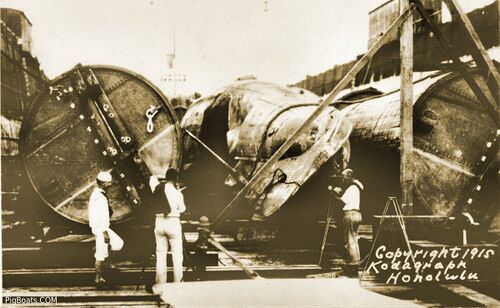

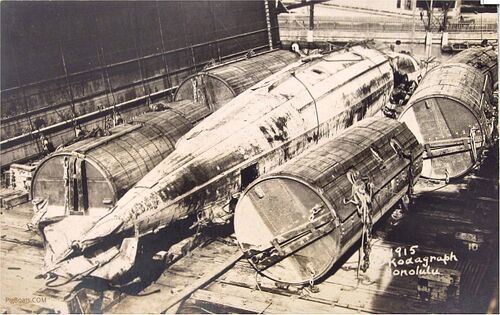

In Drydock

Newspaper photo.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

In this view the boat is upside down, with the port side facing up, looking at the bow. The strake like object at the top is the port side bilge keel, with the main keel just to the right of that. It is important to understand that the leaking battery acid did not cause the implosion. The battery acid weakened the bottom of the hull structure, causing a leak which made the boat heavy, quickly resulting in a loss of control. It was when the boat exceeded crush depth that the hull imploded.

Admiral Clifford J. Boush, Commandant of the 14th Naval District in Hawaii, is seen in the foreground, wearing the long white coat.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

-

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

-

Photo courtesy of Mike Dilley, whose father, Homer 'Pat' Dilley, sailed aboard the USS F-2.

These newly installed experimental propellers were of a special design that were intended for low RPM and high efficiency. It is thought that at high speeds they would have done little to drive the submarine to the surface. The official report stated that these propellers "were the secondary cause of the disaster" by providing insufficient water flow over the stern planes and thus negatively impacting the control of the vessel.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

The extensive damage to the after end of the submarine is very evident. Remembering that the submarine is almost upside down, the twisted piece of metal to the left and twisted towards the camera is actually part of the upper skeg running from the deck to the rudder. It has been bent over more than 90 degrees. The blades of the screws have been bent over and a huge chip has been made in the blade of the screw.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

This photo shows the F-4 with her bow cap rotated to line up with two of her four torpedo tubes. This was done so that the weapons in the tubes could be removed. To access the other two tubes the cap was rotated to the right. To completely close all four tubes the cap was rotated so that the openings were vertical and behind the stem.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

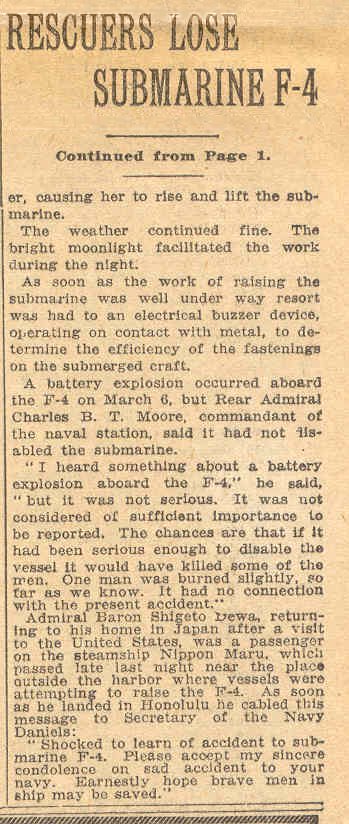

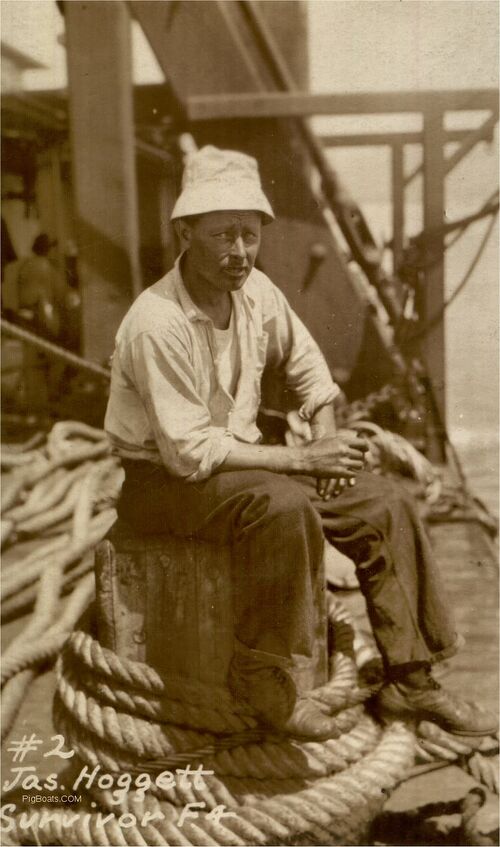

Post Salvage

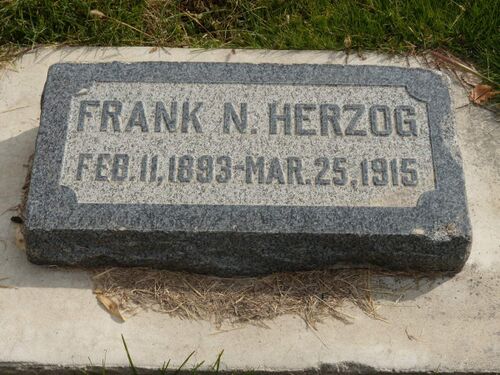

On March 25, 1915 he was left ashore when the F-4 went out on her fateful morning dive. It was a habit for the early submarines to leave one man ashore as a watchman, perhaps to keep an eye on ships material left on the dock and to be a contact person for any information that needs to be reported to the vessel as soon as it returns to port. This was the days before ship radios became common. It happened to be his turn this day.

In most all of the the news reports after the sinking reported he was on 'shore leave' at the time instead of being the "watchman". There was one other man who escaped the sinking, Artheur Mellien, a Chief Machinist Mate, who transferred off the F-4 a few days prior to the sinking.

In the aftermath of the sinking, Hoggett seems to have developed symptoms of PTSD. Accounts of his doings and happenings after the sinking show he seems to have become fairly reckless in his activities and had a number of close to death encounters. Of course nothing was known about PTSD at that time.

He left the Navy in 1916 and when WWI came around he enlisted in the Army Tank Corp in 1918. He survived the war.

James Hoggett died May 31, 1952 in Rolla, MO. He had served on the USS Pensacola, Pittsburgh, Oregon, Maryland, Pennsylvania, the Alert, (a submarine tender), the F-4 and the USS Constellation before being discharged. He was a lucky person to have lived out a normal life span that his shipmates on the F-4 were denied.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

The drawing above was made of the F-4 Automatic Blow System after recovery. It shows the setup and condition of the system made by the crew at the time of the disaster. Short of actually being able to talk to the crew it shows the steps they had taken in the few moments available to them.

This system is something akin to today's Emergency Blow system brought about by the sinking of the USS Thresher (SSN-593) in 1963, although the F-4's system was automatic, whereas the modern system must be manually actuated.

Image from the National Archives.

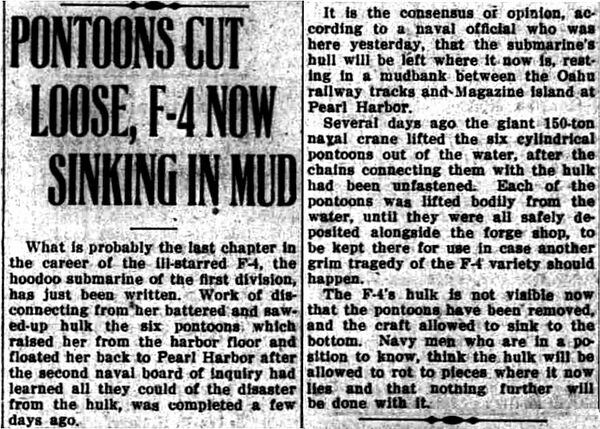

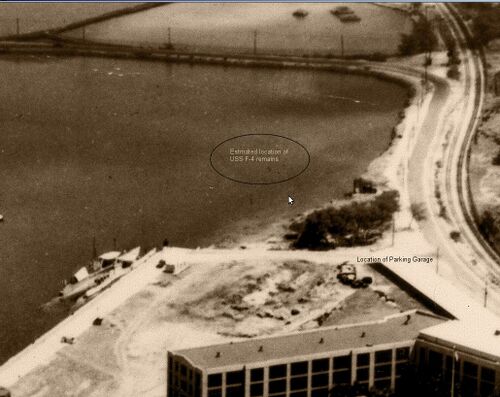

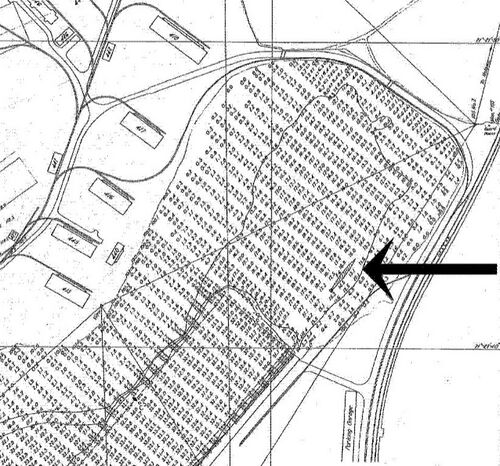

She is still there to this day. In 1940 she was rolled into a trench dredged in the loch bottom to make way for the expansion of docks at the submarine base. She sits at an angle of 43.5 degrees true about 40 feet off the Sierra 13 mooring. About parallel to the old shore line (see below).

Why the Navy never properly disposed of the wreck by scrapping (like the S-51) or by towing her to deep water and sinking her (like the USS Maine) is a bit of a mystery. The webmasters have speculated that the Navy wanted to retain the wreck in an accessible location as evidence until potential future legal proceedings had a chance to play themselves out. Perhaps once it became apparent that there was not going to be any further need to retain the wreck it was decided that doing anything with it was not worth the expense.

Clipping courtesy of the Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

Note in the background that at this point that only a narrow causeway connects the main part of the Submarine Base to Kuahua. As the base rapidly expanded in the 1930's and 1940's this area would be completely filled in and Kuahua would no longer be an islet.

National Archives photo.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

F-4 Legacy

Photo courtesy of the USS Bowfin Submarine Museum and Park.

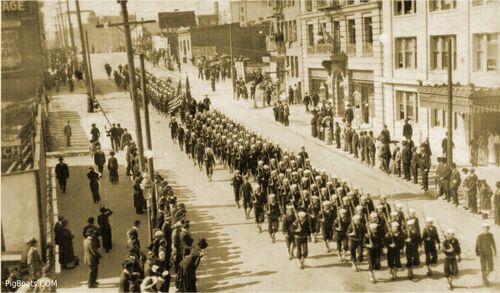

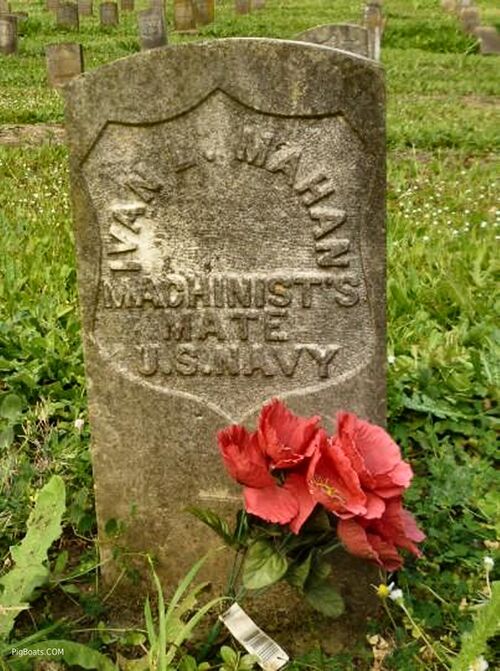

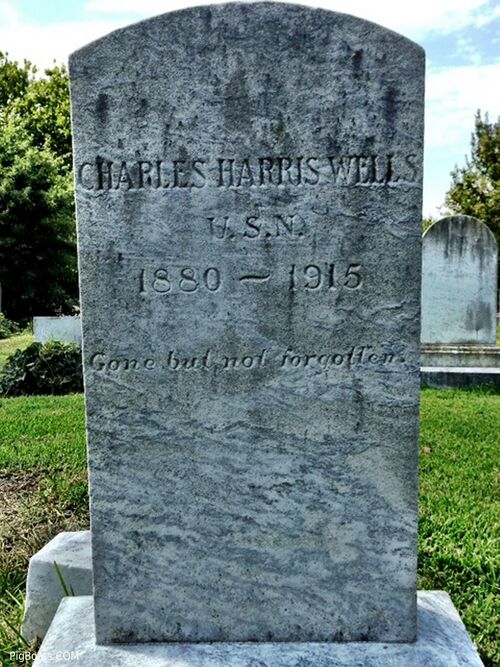

Four of the F-4 crew had been identified and were laid to rest separately at locations chosen by their families.

Newspaper photo.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

Newspaper Article - The body of Frank N. Herzog, bluejacket, who went down with submarine F-4 in Honolulu Harbor in March, arrived in Salt Lake (City) on September 23, after a long journey which began at Honolulu seventeen days previous. Herzog's home was in Salt Lake (City).

Soda Springs Sun; Soda Springs, Idaho. September 30, 1915; Page Three.

Buried in Elmwood Cemetery, Norfolk, Norfolk City, Virginia, USA, Plot ELM EXT, Block 6 Lot 4 Sp 1S

Photo courtesy of Dr. Terrell Newby.