John P. Holland biography and submarines: Difference between revisions

Pbcjohnston (talk | contribs) |

Pbcjohnston (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

The Brayton kerosine engine was the only means of propulsion. There was no battery or electric motor for submerged propulsion. Compressed air tanks fore and aft supplied air for the engine, breathing, and blowing ballast tanks. Exhaust from the engine was vented overboard. Using less air than a modern lawnmower gasoline engine, running the Brayton engine while submerged was at least practical, if not incredibly dangerous due to fumes, heat, and noise. Even still its use would have resulted in a very limited underwater endurance, as rather soon you would simply run out of air with the engine using the bulk of what was stored. | The Brayton kerosine engine was the only means of propulsion. There was no battery or electric motor for submerged propulsion. Compressed air tanks fore and aft supplied air for the engine, breathing, and blowing ballast tanks. Exhaust from the engine was vented overboard. Using less air than a modern lawnmower gasoline engine, running the Brayton engine while submerged was at least practical, if not incredibly dangerous due to fumes, heat, and noise. Even still its use would have resulted in a very limited underwater endurance, as rather soon you would simply run out of air with the engine using the bulk of what was stored. | ||

On May 22, 1878 the boat was ready. It was loaded onto a horse-drawn wagon and taken down to the Upper Passaic River in Paterson. Launched into the river with a crowd of onlookers lining the banks, Holland himself entered the boat and attempted to get the balky Brayton engine running. Accounts differ as to whether he was successful in that particular task. Some say that he needed the extra heat of a shore based steam engine to get the engine running, with another account stating a steam line was run to the sub from another boat and it stayed attached during the trial run in the river with the steam boat following on the surface. At any rate, Holland was successful in running the boat up and down the river, submerging to a depth of 12 feet. It was even reported that he stayed submerged for quite a while in an endurance test, likely with the Brayton engine stopped to preserve air. Holland's notes recorded after the test indicated that he was satisfied with the performance of the Holland I overall, but he noted that the midships mounted diving planes were ineffective due to the fact that they were mounted near the center of gravity of the boat and thus had little effect in controlling depth or angle. He resolved to move them aft in later boats. | On May 22, 1878 the boat was ready. It was loaded onto a horse-drawn wagon and taken down to the Upper Passaic River in Paterson. Launched into the river with a crowd of onlookers lining the banks (reportedly including agents of the Royal Navy), Holland himself entered the boat and attempted to get the balky Brayton engine running. Accounts differ as to whether he was successful in that particular task. Some say that he needed the extra heat of a shore based steam engine to get the engine running, with another account stating a steam line was run to the sub from another boat and it stayed attached during the trial run in the river with the steam boat following on the surface. At any rate, Holland was successful in running the boat up and down the river, submerging to a depth of 12 feet. It was even reported that he stayed submerged for quite a while in an endurance test, likely with the Brayton engine stopped to preserve air. Holland's notes recorded after the test indicated that he was satisfied with the performance of the Holland I overall, but he noted that the midships mounted diving planes were ineffective due to the fact that they were mounted near the center of gravity of the boat and thus had little effect in controlling depth or angle. He resolved to move them aft in later boats. This was a fact of physics taught to Holland the hard way that was apparently lost on his eventual competitor [[Simon Lake non-Navy Submarines|'''Simon Lake''']], who favored midships mounted diving planes. Lake also had to learn that lesson the hard way. | ||

Members of the Fenian Brotherhood were present for the test and they were very pleased. They immediately offered to finance a follow-on boat. The Holland I was stripped of useful equipment by Holland, and he deliberately scuttled the boat in the Passaic River near the Spruce Street bridge. | Members of the Fenian Brotherhood were present for the test and they were very pleased. They immediately offered to finance a follow-on boat. The Holland I was stripped of useful equipment by Holland, and he deliberately scuttled the boat in the Passaic River near the Spruce Street bridge. Some time later some local men salvaged the conning tower for scrap, but in 1927 the entire boat was raised from the mud and donated to the Paterson Museum. The photo above is a recent shot of the boat as it currently sits in the museum after restoration work and receiving a replacement conning tower. | ||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | [[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

[[File:Fenian Ram diagram.jpg|left|550px|Diagram courtesy of R.K. Morris and Gary McCue.]] | [[File:Fenian Ram diagram.jpg|left|550px|Diagram courtesy of R.K. Morris and Gary McCue.]] | ||

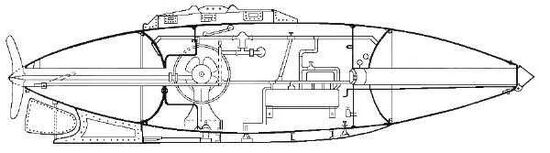

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">Holland immediately set to work on the new boat financed by the Fenians. He had a much more advanced design already available and $20,000 bought the Fenians a considerable advancement over the diminutive Holland I. Holland contracted with the Delamater Iron Works in New York City and the boat was laid down at their facility on the Hudson River at the foot of W 13th and W 14th Streets. Dubbed the Holland II by its inventor, the new boat was to be 31 feet long, six feet in diameter, and displaced a whopping 19 tons. It had a single, two bladed, axial mounted propeller with a rudder mounted ventrally below the tip of the stern. Holland made the major change of moving the diving planes to the stern on either side of the propeller where they would have a much greater | <div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">Holland immediately set to work on the new boat financed by the Fenians. He had a much more advanced design already available and $20,000 bought the Fenians a considerable advancement over the diminutive Holland I. Holland contracted with the Delamater Iron Works in New York City and the boat was laid down at their facility on the Hudson River at the foot of W 13th and W 14th Streets. Dubbed the Holland II by its inventor, the new boat was to be 31 feet long, six feet in diameter, and displaced a whopping 19 tons. It had a single, two bladed, axial mounted propeller with a rudder mounted ventrally below the tip of the stern. Holland made the major change of moving the diving planes to the stern on either side of the propeller where they would have a much greater physical effect. | ||

Once again Holland turned to the Brayton engine for motive power despite the troubles he had with it earlier | Once again Holland turned to the Brayton engine for motive power despite the troubles he had with it earlier. This was mostly because in 1878 it was the only practical internal combustion engine available. Holland extensively modified the engine with an eye towards improving efficiency. It was a two cylinder, 17 horsepower engine and was sited on the starboard side of the boat's only compartment. Once again the exhaust from the engine was continuously vented overboard, this time assisted by a check valve that prevented water from entering. An air compressor ran down the port side and was powered off the Brayton engine. A large flywheel that assisted in keeping consistent propeller shaft revolutions sat on the port side. Large ballast tanks surrounded the propeller shaft aft and the single 9-inch diameter "torpedo tube" forward. The operator sat in a seat at the aft end of the compartment with his head up in the small conning tower. An engineer worked the engine, the compressor, and ballast controls. A gunner was responsible for firing the tube. The tube was closed with a breech door inside the boat, and with a pointed cap on the muzzle end at the tip of the bow. | ||

<gallery mode="nolines" perrow=3 widths="380px" heights="280px"> | <gallery mode="nolines" perrow=3 widths="380px" heights="280px"> | ||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">There is some debate in various sources as to the exact weapon the submarine carried. It has been described as an "Ericsson" torpedo, designed by the famous naval architect John Ericsson. Holland himself stated that the weapon had a range of only 50-60 yards underwater. This can be interpreted to mean that the weapon was more of a projectile rather than a self propelled torpedo, simply shot out of the tube like a bullet out of a gun. However, if the boat broached the bow the "torpedo" could be fired along the surface up to 300 yards. It had a 100 lb warhead, likely of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitrocellulose '''wet guncotton (nitrocellulose)''']. | <div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">There is some debate in various sources as to the exact weapon the submarine carried. It has been described as an "Ericsson" torpedo, designed by the famous naval architect John Ericsson. Holland himself stated that the weapon had a range of only 50-60 yards underwater. This can be interpreted to mean that the weapon was more of a projectile rather than a self propelled torpedo, simply shot out of the tube like a bullet out of a gun. However, if the boat broached the bow the "torpedo" could be fired along the surface up to 300 yards. It had a 100 lb warhead, likely of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitrocellulose '''wet guncotton (nitrocellulose)''']. | ||

The boat, now dubbed the "Fenian Ram" by a reporter who thought it would ram ships, was ready for testing in 1881. Holland made a series of short shakedown cruises in the Hudson River through 1881 and 1882, gathering data on performance and tweaking the design. By 1883 he was running extended cruises in the Hudson River and The Narrows off Brooklyn and Staten Island. The Fenian Ram showed itself to be a remarkable boat. The tests were well covered by the press and the fact that the boat had been financed by Fenian revolutionaries was essentially an open secret. Holland was able to control it easily both surfaced and submerged and could routinely run submerged at depths up to 50 feet. It was also reported that Holland could spend "several hours" submerged in the boat, undoubtedly with the Brayton engine secured to preserve air. In one test of the pneumatic tube an Ericsson dummy projectile was fired with the tube muzzle about three feet below the water. 300 psi of air pressure forced the projectile out of the tube eight to ten feet before it broke the surface and rose "sixty to seventy feet in the air" before it reentered the water, burying itself in the river mud. Historian Lawrence Goldstone called the Ram "the most advanced submarine in the world at that time". He was correct. Despite the success of the Fenian Ram, the response from the U.S. Navy was lukewarm at best. The service was hesitant to look seriously at submarines at this time, mostly due to bureaucratic and internal social | The boat, now dubbed the "Fenian Ram" by a reporter who thought it would ram ships, was ready for testing in 1881. Holland made a series of short shakedown cruises in the Hudson River through 1881 and 1882, gathering data on performance and tweaking the design. By 1883 he was running extended cruises in the Hudson River and The Narrows off Brooklyn and Staten Island. The Fenian Ram showed itself to be a remarkable boat. The tests were well covered by the press and the fact that the boat had been financed by Fenian revolutionaries was essentially an open secret. Holland was able to control it easily both surfaced and submerged and could routinely run submerged at depths up to 50 feet. It was also reported that Holland could spend "several hours" submerged in the boat, undoubtedly with the Brayton engine secured to preserve air. In one test of the pneumatic tube an Ericsson dummy projectile was fired with the tube muzzle about three feet below the water. 300 psi of air pressure forced the projectile out of the tube eight to ten feet before it broke the surface and rose "sixty to seventy feet in the air" before it reentered the water, burying itself in the river mud. Historian Lawrence Goldstone called the Ram "the most advanced submarine in the world at that time". He was correct. There was nothing else as capable anywhere in the world. | ||

Despite the success of the Fenian Ram, the response from the U.S. Navy was lukewarm at best. The service was hesitant to look seriously at submarines at this time, mostly due to bureaucratic inertia, unreasonable adherence to tradition, and an internal social dynamic that made change slow at best and an anathema at worst. | |||

Holland, ever the inveterate tinkerer, was never fully satisfied with the Ram's performance. He convinced the Fenians to finance a sub-scale duplicate of the boat so that he could test new ideas without having to modify the Ram before the concepts were proven. The new boat was outwardly quite similar to the Fenian Ram, but only 14 feet long with a single operator and a one ton displacement. Holland named this boat the Holland III. Unfortunately no photographs of the Holland III exist. Testing of the smaller boat ran in parallel with the Fenian Ram. | Holland, ever the inveterate tinkerer, was never fully satisfied with the Ram's performance. He convinced the Fenians to finance a sub-scale duplicate of the boat so that he could test new ideas without having to modify the Ram before the concepts were proven. The new boat was outwardly quite similar to the Fenian Ram, but only 14 feet long with a single operator and a one ton displacement. Holland named this boat the Holland III. Unfortunately no photographs of the Holland III exist. Testing of the smaller boat ran in parallel with the Fenian Ram. | ||

The Fenians proved themselves to be surprisingly inept, both as terrorists and as financiers. Strong and | The Fenians proved themselves to be surprisingly inept, both as terrorists and as financiers. Strong and vainglorious personalities with little to no organizational skills fractured the society's plans, and graft and corruption squandered the money they had raised. By the fall of 1883 the society was nearly broke, and the members of the leadership hatched a plan to recover a portion of the nearly $60,000 (over $2,000,000 in 2024 dollars) they had invested in the Fenian Ram. In November, 1883, late at night, a group led by Fenian leader John Breslin used a permission slip with Holland's forged signature to gain access to the Fenian Ram and the Holland III at their slip on the Hudson River. Using a tugboat they towed both boats away, intending to spirit them to a yard in New Haven, CT where they could be sold off. Unfortunately, they neglected to secure the hatch on the Holland III and the small boat was swamped and sank under tow in the East River. | ||

The motley force managed to make it to New Haven where apparently Breslin had a change of heart about selling off the Fenian Ram. He and a group of men attempted to operate the boat in | The motley force managed to make it to New Haven where apparently Breslin had a change of heart about selling off the Fenian Ram. He and a group of men attempted to operate the boat in New Haven Harbor, but found they didn't understand how to operate the boat's systems without Holland. In a move laden with unmitigated chutzpah, Breslin then contacted Holland and asked him to help with the operation of the boat that they had just stolen from him. Holland, thoroughly disgusted and disillusioned with the inept shenanigans of the Fenians, steadfastly refused and washed his hands of the whole affair. | ||

[[File:Fenian Ram Hibernians.jpg|left|300px|Photo courtesy of The Ancient Order of Hibernians]] | [[File:Fenian Ram Hibernians.jpg|left|300px|Photo courtesy of The Ancient Order of Hibernians]] | ||

[[File:Paterson Museum (NJ) images (45) number 36 Early submarine.jpg|right| | [[File:Paterson Museum (NJ) images (45) number 36 Early submarine.jpg|right|300px|Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]] | ||

Breslin and his cohorts, unable to operate or sell the boat had it hauled out of the water and stored in a woodshed off the Mill River in New Haven. There it sat until 1916 when Irish sympathizers moved it to Madison Square Garden in New York City and put it on display to raise money for the victims of the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Easter_Rising '''Easter Rising''']. After serving its purpose there it was moved to the grounds of the New York State Marine School where it stayed until 1927. It was then purchased and moved to West Side Park in Paterson, as shown in the photo at left. Note that the boat is missing the pointed bow cap for the torpedo tube. It stayed there in the park displayed outside in the elements until 2001. It was then acquired by the Paterson Museum and moved indoors, where it went through a preservation process that allows visitors to view it to this day. It sits directly adjacent to its predecessor the Holland I. The photo on the right gives a good view of the stern diving planes, with one of the propeller blades showing signs of damage. The rudder is also suffering from corrosion damage. | Breslin and his cohorts, unable to operate or sell the boat, had it hauled out of the water and stored in a woodshed off the Mill River in New Haven. There it sat until 1916 when Irish sympathizers moved it to Madison Square Garden in New York City and put it on display to raise money for the victims of the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Easter_Rising '''Easter Rising''']. After serving its purpose there it was moved to the grounds of the New York State Marine School where it stayed until 1927. It was then purchased and moved to West Side Park in Paterson, as shown in the photo at left. Note that the boat is missing the pointed bow cap for the torpedo tube. It stayed there in the park displayed outside in the elements until 2001. It was then acquired by the Paterson Museum and moved indoors, where it went through a preservation process that allows visitors to view it to this day. It sits directly adjacent to its predecessor the Holland I. The photo on the right gives a good view of the stern diving planes, with one of the propeller blades showing signs of damage. The rudder is also suffering from corrosion damage. | ||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | [[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | ||

| Line 76: | Line 78: | ||

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">The Fenian affair had left Holland broke and out of work. In December, 1883 he was forced to take a job as an ordinary draftsman with the Brayton company. Around Christmas that year Holland met Navy LT William Kimball at a party. Kimball was interested in the potential of submarines, and he approached Holland about coming to work for the Bureau of Ordnance as a draftsman to develop submarines. Kimball was unable to obtain funds for the position as Congress was in recess and Holland was not of the mind to wait for the bureaucracy to clear up. | <div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">The Fenian affair had left Holland broke and out of work. In December, 1883 he was forced to take a job as an ordinary draftsman with the Brayton company. Around Christmas that year Holland met Navy LT William Kimball at a party. Kimball was interested in the potential of submarines, and he approached Holland about coming to work for the Bureau of Ordnance as a draftsman to develop submarines. Kimball was unable to obtain funds for the position as Congress was in recess and Holland was not of the mind to wait for the bureaucracy to clear up. | ||

Kimball had also introduced Holland to [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmund_Zalinski '''LT Edmund Zalinski'''] of the U.S. Army. Zalinski had invented a pneumatically fired gun that would shoot a dynamite projectile. The Zalinski gun was similar to the tube installed in the Fenian Ram, only much higher powered | Kimball had also introduced Holland to [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmund_Zalinski '''LT Edmund Zalinski'''] of the U.S. Army. Zalinski had invented a pneumatically fired gun that would shoot a dynamite projectile. The Zalinski gun was similar to the tube installed in the Fenian Ram, only much more technically refined and higher powered. He had been successful in marketing the idea and had a company formed to produce it for the Army Coast Artillery Corps. Zalinski saw potential in a Holland submarine employing one of his "dynamite guns", and he and Holland met again in early 1884 in Brooklyn. The two formed the Nautilus Submarine Boat Company that year to produce submarines armed with the Zalinski gun for use in Army coastal defense. | ||

[[File:Zalinski Boat.jpg|left|500px|Photograph courtesy of R.K. Morris and Gary McCue.]] | [[File:Zalinski Boat.jpg|left|500px|Photograph courtesy of R.K. Morris and Gary McCue.]] | ||

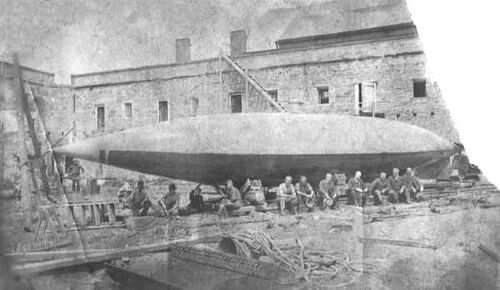

Holland immediately began work on a boat that he called the Holland IV on the grounds of the former [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Lafayette '''Fort Lafayette'''] on an island in The Narrows just north of Fort Hamilton, a site now dominated by the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. The boat was to be 50 feet long with a displacement of 28 tons. An operator would guide the boat with his head up in a small conning tower, using a [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camera_lucida '''camera lucida'''] as a primitive periscope. Propulsion was once again a Brayton cycle engine, with no batteries or motors. An engineer would control the engine, diving planes, and ballast. A possible future upgrade would have the boat operated by only one man. The boat was to be armed with a single Zalinski gun in the bow. The intended mode of operation was to sight the target while submerged, broach the bow, and fire the gun with the projectile flying through the air to the target. The photo at left is a very rare photo of the Holland IV, now colloquially known as "The Zalinski Boat", under construction at Fort Lafayette. | Holland immediately began work on a boat that he called the Holland IV on the grounds of the former [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Lafayette '''Fort Lafayette'''] on an island in The Narrows just north of Fort Hamilton, a site now dominated by the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. The boat was to be 50 feet long with a displacement of 28 tons. An operator would guide the boat with his head up in a small conning tower, using a [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camera_lucida '''camera lucida'''] as a primitive periscope. Propulsion was once again a Brayton cycle engine, with no batteries or motors. An engineer would control the engine, diving planes, and ballast. A possible future upgrade would have the boat operated by only one man. The boat was to be armed with a single Zalinski gun in the bow. The intended mode of operation was to sight the target while broached, approach submerged, broach the bow, and fire the gun with the projectile flying through the air to the target. The photo at left is a very rare photo of the Holland IV, now colloquially known as "The Zalinski Boat", under construction at Fort Lafayette. | ||

Almost immediately Holland ran into difficulties with his business partners. Zalinski's investors were leery of the concept and | Almost immediately Holland ran into difficulties with his business partners. Zalinski's investors were leery of the concept and rather parsimonious with the funding. Holland was forced to make compromises in the design to fit the available funds, so the extraordinary decision was made to build the hull out of wood, attached to interior steel framing. Zalinski himself proved to be only marginally competent in construction matters. He was disinterested in the building process until pressure from the investors was levied on him, then he forcably inserted himself into the final stages of construction. He took credit for technical matters that he had no knowledge of, angering Holland. He bluntly forced Holland to launch the boat before it and the launching slip was ready. In addition, the launching track was awkwardly placed. The boat was being built on a slip in a courtyard between two buildings. The elevated launch slip had to go from the courtyard and across a sand berm before it could reach water. Holland pleaded with Zalinski for more time to shore up the cradle and strengthen the launch track, but Zalinski persisted and the boat slid down the ways on September 4, 1885. The shoring under the boat broke under the strain and the boat fell off the cradle and struck pilings just as it reached the water. The bottom and one side of the boat was stove in and badly damaged, and it partially flooded. | ||

Contrary to reports in the popular press, in particular an article in Scientific American in 1886, the Holland IV never left the spot it fell in. It never got underway and never submerged. These false reports were likely the product of Zalinski's ignorance of technical matters and some rather shameless self-promotion. Holland's own notes show that it was impossible to repair the boat with the funding that remained. Holland and his team stripped the boat of any useful equipment and the rest of the hulk was scrapped on the spot. The Nautilus Submarine Boat Company dissolved shortly thereafter. | Contrary to reports in the popular press, in particular an article in Scientific American in 1886, the Holland IV never left the spot it fell in. It never got underway and never submerged. These false reports were likely the product of Zalinski's ignorance of technical matters and some rather shameless self-promotion on his part. Holland's own notes show that it was impossible to repair the boat with the funding that remained. Holland and his team stripped the boat of any useful equipment and the rest of the hulk was scrapped on the spot. The Nautilus Submarine Boat Company dissolved shortly thereafter. | ||

Totally deflated at the failure of the Zalinski project, Holland was once again out of work. Kimball had been unable to get funding for the BuOrd draftsman position, so once the Zalinski affair was ended Holland reluctantly returned to work for private firms as a draftsman. | Totally deflated at the failure of the Zalinski project, Holland was once again out of work. Kimball had been unable to get funding for the BuOrd draftsman position, so once the Zalinski affair was ended Holland reluctantly returned to work for private firms as a draftsman. | ||

| Line 95: | Line 97: | ||

<div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">By 1886 the U.S. Navy was beginning to wake up and realize the potential of the submarine. Development in Europe and Holland's activities in the U.S. was making a handful of naval officers in this country take notice. In general, the U.S. Navy was coming out of a 20 year malaise and period of neglect that had set in after the conclusion of the Civil War and the Navy Department was becoming more reform minded. There was still a long way to go, and hidebound tradition still got in the way of clear thinking. | <div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="color:#00008B">By 1886 the U.S. Navy was beginning to wake up and realize the potential of the submarine. Development in Europe and Holland's activities in the U.S. was making a handful of naval officers in this country take notice. In general, the U.S. Navy was coming out of a 20 year malaise and period of neglect that had set in after the conclusion of the Civil War and the Navy Department was becoming more reform minded. There was still a long way to go, and hidebound tradition still got in the way of clear thinking. | ||

Holland himself continued to eke out a living as best he could, holding positions as a draftsman. | Holland himself continued to eke out a living as best he could, holding positions as a draftsman. On January 17, 1887 at age 45 he married Margaret Foley in Brooklyn and their first child, John Jr. was born in the next year. Unfortunately the child died in infancy. John and Margaret would go on to have six more children, another of which died as an infant. | ||

In 1888 | In 1888 the fog of tradition was slowly lifting in the Navy Department and progress was being made. They held an open competition for the design of a submarine torpedo boat. LT William Kimball, the same officer that tried to get Holland a job with BuOrd, convinced the Secretary of the Navy of the need to investigate the potential of the submarine. The specifications drawn up for the 1888 competition were quite advanced for the time: speed 15 knots on the surface and 8 knots submerged, be able to remained submerged for up to two hours at a time, a test depth of 150 feet, complete a turn within a radius of four times its length, deliver a torpedo with a warhead of 100 lbs, and carry provisions for 90 hours of operation. Holland had a design ready to go and even had an arrangement with the prestigious Cramp & Sons Shipbuilding in Philadelphia to produce the boat. Three others submitted designs as well, but Holland's reputation had preceded him and he was declared the winner of the competition. | ||

Then, just as the results were released, Secretary of the Navy William C. Whitney had a sudden change of heart. Likely due to political pressure he abruptly canceled the competition, leaving Holland in the lurch. The incoming Harrison administration did not support the idea either, instead preferring to build up the surface fleet. Holland was totally deflated at this double defeat, and accepted a job once again as a draftsman with the Morris & Cummings Dredging Company. Holland had conferred with engineer Charles Morris during the fitting out of the Fenian Ram, and Morris was more than happy to take Holland on at the company. Holland worked for Morris & Cummings until 1893, content with the steady, if not unremarkable, income. | Then, just as the results were released, Secretary of the Navy William C. Whitney had a sudden change of heart. Likely due to political and internal pressure he abruptly canceled the competition, leaving Holland in the lurch. The incoming Harrison administration did not support the idea either, instead preferring to build up the surface fleet. Holland was totally deflated at this double defeat, and accepted a job once again as a draftsman with the Morris & Cummings Dredging Company. Holland had conferred with engineer Charles Morris during the fitting out of the Fenian Ram, and Morris was more than happy to take Holland on at the company. Holland worked for Morris & Cummings until 1893, content with the steady, if not unremarkable, income. | ||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | [[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | ||

Revision as of 02:42, 10 January 2025

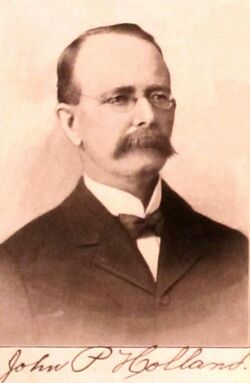

The early years

In fact, John did not speak any English until he attended the St. Macreehy's National School just down the street from the house in Liscannor. John proved to be a capable student, but struggled with serious health issues, including poor eyesight. His family survived the Great Famine in Ireland relatively intact only because his father's employment gave them a relatively clean and well maintained house. John witnessed the depredations of the Great Famine firsthand, and the British government's lack of response instilled in him a deeply seated animosity towards the British. These attitudes proved to be part of a two sided coin. His strong animosity towards the British was contrasted by his generally affable manner, combined with a generalized pacifism instilled by his Catholic beliefs.

John took to his studies with vigor and by 1853 his family moved to Limerick with John attending the Christian Brothers School there. By age 17 he joined the brotherhood and was given the Christian name Philip, which he retained as his middle name for the rest of his life. He was soon accepted as a teacher. During this period he fell under the influence of Brother James Dominic Burke, a renowned man of science. John took to the science studies with gusto, displaying a tremendous mechanical aptitude. Brother Burke was conducting experiments in underwater propulsion using electricity and the firing of torpedoes against ships in a model basin. These activities struck a spark in John, and he began his lifelong fascination with submarines.

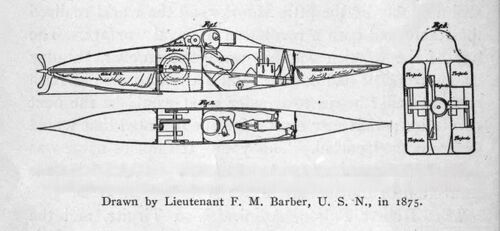

When exactly he designed his first submarine is somewhat up for debate, but it is quite likely that he made his first sketches during the period of 1858-1872, as he moved in and out of various Christian Brothers sponsored teaching positions while dealing with several health issues. Although this sketch here comes from a later interpretation, this is essentially the first design from the fertile mind of John P. Holland. As you can see this was a human powered boat, with a recumbent seated operator wearing a diving suit. Ballast controls were between the operator's legs as he pushed two treadles that were mechanically linked to the propeller shaft. The boat was rectangular in cross section, with four detachable "torpedoes" (i.e. mines) in a compartment behind the operator. This design was never built, as even John could recognize its limitations. In some texts it is referred to as the "Holland I" design, although Holland himself never referred to it in this fashion.

1872 would prove to be a watershed year in the life of John P. Holland. That year he became involved in an effort sponsored by subset of the Christian Brothers that campaigned for better and more efficient schools. This effort angered the bulk of the group, who saw it as an affront to their teaching philosophy. John was also continuously battling health issues, and these stresses caused him to decline perpetual vows with the order in late December 1872. His father had passed away many years earlier, and his elderly mother and brother Michael had emigrated to the U.S. He decided to join them and set sail for a new life in the states on May 26, 1873. He spent the summer and fall in Liverpool while he awaited further passage, finally landing in Boston in November, 1873. Nearly broke when he landed, one of the few possessions that he had upon arrival were the drawings of his initial submarine design.

He no sooner landed in a wintry Boston when he slipped and fell on an icy street. He broke a leg, and spent the next three months laid up in bed as he healed. He used the time to go back and reconsider his submarine designs, refining them and improving the drawings. John landed a job at the St. John's Parochial School in Paterson, NJ and began working in earnest on his submarine ideas in his spare time. After consulting with a friend in 1875, he submitted the initial pedal powered design to the Navy Department. The Navy utterly rejected Holland's work, with the Secretary calling it "a fantastic scheme of a civilian landsman."

It was at this time that his brother Michael introduced him to members of the Fenian Brotherhood, an American based society of Irish expatriates whose goal was the overthrow of British influence and control in Ireland. The Fenians did not shy away from violence as a means to an end, and Holland's technical expertise and fervent belief in a free Ireland impressed the Fenian leadership. They saw his concepts as a means of hitting back at the British Royal Navy.

Holland I

The Brayton kerosine engine was the only means of propulsion. There was no battery or electric motor for submerged propulsion. Compressed air tanks fore and aft supplied air for the engine, breathing, and blowing ballast tanks. Exhaust from the engine was vented overboard. Using less air than a modern lawnmower gasoline engine, running the Brayton engine while submerged was at least practical, if not incredibly dangerous due to fumes, heat, and noise. Even still its use would have resulted in a very limited underwater endurance, as rather soon you would simply run out of air with the engine using the bulk of what was stored.

On May 22, 1878 the boat was ready. It was loaded onto a horse-drawn wagon and taken down to the Upper Passaic River in Paterson. Launched into the river with a crowd of onlookers lining the banks (reportedly including agents of the Royal Navy), Holland himself entered the boat and attempted to get the balky Brayton engine running. Accounts differ as to whether he was successful in that particular task. Some say that he needed the extra heat of a shore based steam engine to get the engine running, with another account stating a steam line was run to the sub from another boat and it stayed attached during the trial run in the river with the steam boat following on the surface. At any rate, Holland was successful in running the boat up and down the river, submerging to a depth of 12 feet. It was even reported that he stayed submerged for quite a while in an endurance test, likely with the Brayton engine stopped to preserve air. Holland's notes recorded after the test indicated that he was satisfied with the performance of the Holland I overall, but he noted that the midships mounted diving planes were ineffective due to the fact that they were mounted near the center of gravity of the boat and thus had little effect in controlling depth or angle. He resolved to move them aft in later boats. This was a fact of physics taught to Holland the hard way that was apparently lost on his eventual competitor Simon Lake, who favored midships mounted diving planes. Lake also had to learn that lesson the hard way.

Members of the Fenian Brotherhood were present for the test and they were very pleased. They immediately offered to finance a follow-on boat. The Holland I was stripped of useful equipment by Holland, and he deliberately scuttled the boat in the Passaic River near the Spruce Street bridge. Some time later some local men salvaged the conning tower for scrap, but in 1927 the entire boat was raised from the mud and donated to the Paterson Museum. The photo above is a recent shot of the boat as it currently sits in the museum after restoration work and receiving a replacement conning tower.

Holland II ("Fenian Ram") & Holland III

Once again Holland turned to the Brayton engine for motive power despite the troubles he had with it earlier. This was mostly because in 1878 it was the only practical internal combustion engine available. Holland extensively modified the engine with an eye towards improving efficiency. It was a two cylinder, 17 horsepower engine and was sited on the starboard side of the boat's only compartment. Once again the exhaust from the engine was continuously vented overboard, this time assisted by a check valve that prevented water from entering. An air compressor ran down the port side and was powered off the Brayton engine. A large flywheel that assisted in keeping consistent propeller shaft revolutions sat on the port side. Large ballast tanks surrounded the propeller shaft aft and the single 9-inch diameter "torpedo tube" forward. The operator sat in a seat at the aft end of the compartment with his head up in the small conning tower. An engineer worked the engine, the compressor, and ballast controls. A gunner was responsible for firing the tube. The tube was closed with a breech door inside the boat, and with a pointed cap on the muzzle end at the tip of the bow.

-

View from forward looking aft at the operator seat and flywheel, with the Brayton engine on the left.

-

The Brayton engine on the starboard side.

-

The air compressor on the port side.

Photos via Wikimedia Commons.

The boat, now dubbed the "Fenian Ram" by a reporter who thought it would ram ships, was ready for testing in 1881. Holland made a series of short shakedown cruises in the Hudson River through 1881 and 1882, gathering data on performance and tweaking the design. By 1883 he was running extended cruises in the Hudson River and The Narrows off Brooklyn and Staten Island. The Fenian Ram showed itself to be a remarkable boat. The tests were well covered by the press and the fact that the boat had been financed by Fenian revolutionaries was essentially an open secret. Holland was able to control it easily both surfaced and submerged and could routinely run submerged at depths up to 50 feet. It was also reported that Holland could spend "several hours" submerged in the boat, undoubtedly with the Brayton engine secured to preserve air. In one test of the pneumatic tube an Ericsson dummy projectile was fired with the tube muzzle about three feet below the water. 300 psi of air pressure forced the projectile out of the tube eight to ten feet before it broke the surface and rose "sixty to seventy feet in the air" before it reentered the water, burying itself in the river mud. Historian Lawrence Goldstone called the Ram "the most advanced submarine in the world at that time". He was correct. There was nothing else as capable anywhere in the world.

Despite the success of the Fenian Ram, the response from the U.S. Navy was lukewarm at best. The service was hesitant to look seriously at submarines at this time, mostly due to bureaucratic inertia, unreasonable adherence to tradition, and an internal social dynamic that made change slow at best and an anathema at worst.

Holland, ever the inveterate tinkerer, was never fully satisfied with the Ram's performance. He convinced the Fenians to finance a sub-scale duplicate of the boat so that he could test new ideas without having to modify the Ram before the concepts were proven. The new boat was outwardly quite similar to the Fenian Ram, but only 14 feet long with a single operator and a one ton displacement. Holland named this boat the Holland III. Unfortunately no photographs of the Holland III exist. Testing of the smaller boat ran in parallel with the Fenian Ram.

The Fenians proved themselves to be surprisingly inept, both as terrorists and as financiers. Strong and vainglorious personalities with little to no organizational skills fractured the society's plans, and graft and corruption squandered the money they had raised. By the fall of 1883 the society was nearly broke, and the members of the leadership hatched a plan to recover a portion of the nearly $60,000 (over $2,000,000 in 2024 dollars) they had invested in the Fenian Ram. In November, 1883, late at night, a group led by Fenian leader John Breslin used a permission slip with Holland's forged signature to gain access to the Fenian Ram and the Holland III at their slip on the Hudson River. Using a tugboat they towed both boats away, intending to spirit them to a yard in New Haven, CT where they could be sold off. Unfortunately, they neglected to secure the hatch on the Holland III and the small boat was swamped and sank under tow in the East River.

The motley force managed to make it to New Haven where apparently Breslin had a change of heart about selling off the Fenian Ram. He and a group of men attempted to operate the boat in New Haven Harbor, but found they didn't understand how to operate the boat's systems without Holland. In a move laden with unmitigated chutzpah, Breslin then contacted Holland and asked him to help with the operation of the boat that they had just stolen from him. Holland, thoroughly disgusted and disillusioned with the inept shenanigans of the Fenians, steadfastly refused and washed his hands of the whole affair.

Breslin and his cohorts, unable to operate or sell the boat, had it hauled out of the water and stored in a woodshed off the Mill River in New Haven. There it sat until 1916 when Irish sympathizers moved it to Madison Square Garden in New York City and put it on display to raise money for the victims of the Easter Rising. After serving its purpose there it was moved to the grounds of the New York State Marine School where it stayed until 1927. It was then purchased and moved to West Side Park in Paterson, as shown in the photo at left. Note that the boat is missing the pointed bow cap for the torpedo tube. It stayed there in the park displayed outside in the elements until 2001. It was then acquired by the Paterson Museum and moved indoors, where it went through a preservation process that allows visitors to view it to this day. It sits directly adjacent to its predecessor the Holland I. The photo on the right gives a good view of the stern diving planes, with one of the propeller blades showing signs of damage. The rudder is also suffering from corrosion damage.

Holland IV (aka "The Zalinski Boat")

Kimball had also introduced Holland to LT Edmund Zalinski of the U.S. Army. Zalinski had invented a pneumatically fired gun that would shoot a dynamite projectile. The Zalinski gun was similar to the tube installed in the Fenian Ram, only much more technically refined and higher powered. He had been successful in marketing the idea and had a company formed to produce it for the Army Coast Artillery Corps. Zalinski saw potential in a Holland submarine employing one of his "dynamite guns", and he and Holland met again in early 1884 in Brooklyn. The two formed the Nautilus Submarine Boat Company that year to produce submarines armed with the Zalinski gun for use in Army coastal defense.

Holland immediately began work on a boat that he called the Holland IV on the grounds of the former Fort Lafayette on an island in The Narrows just north of Fort Hamilton, a site now dominated by the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. The boat was to be 50 feet long with a displacement of 28 tons. An operator would guide the boat with his head up in a small conning tower, using a camera lucida as a primitive periscope. Propulsion was once again a Brayton cycle engine, with no batteries or motors. An engineer would control the engine, diving planes, and ballast. A possible future upgrade would have the boat operated by only one man. The boat was to be armed with a single Zalinski gun in the bow. The intended mode of operation was to sight the target while broached, approach submerged, broach the bow, and fire the gun with the projectile flying through the air to the target. The photo at left is a very rare photo of the Holland IV, now colloquially known as "The Zalinski Boat", under construction at Fort Lafayette.

Almost immediately Holland ran into difficulties with his business partners. Zalinski's investors were leery of the concept and rather parsimonious with the funding. Holland was forced to make compromises in the design to fit the available funds, so the extraordinary decision was made to build the hull out of wood, attached to interior steel framing. Zalinski himself proved to be only marginally competent in construction matters. He was disinterested in the building process until pressure from the investors was levied on him, then he forcably inserted himself into the final stages of construction. He took credit for technical matters that he had no knowledge of, angering Holland. He bluntly forced Holland to launch the boat before it and the launching slip was ready. In addition, the launching track was awkwardly placed. The boat was being built on a slip in a courtyard between two buildings. The elevated launch slip had to go from the courtyard and across a sand berm before it could reach water. Holland pleaded with Zalinski for more time to shore up the cradle and strengthen the launch track, but Zalinski persisted and the boat slid down the ways on September 4, 1885. The shoring under the boat broke under the strain and the boat fell off the cradle and struck pilings just as it reached the water. The bottom and one side of the boat was stove in and badly damaged, and it partially flooded.

Contrary to reports in the popular press, in particular an article in Scientific American in 1886, the Holland IV never left the spot it fell in. It never got underway and never submerged. These false reports were likely the product of Zalinski's ignorance of technical matters and some rather shameless self-promotion on his part. Holland's own notes show that it was impossible to repair the boat with the funding that remained. Holland and his team stripped the boat of any useful equipment and the rest of the hulk was scrapped on the spot. The Nautilus Submarine Boat Company dissolved shortly thereafter.

Totally deflated at the failure of the Zalinski project, Holland was once again out of work. Kimball had been unable to get funding for the BuOrd draftsman position, so once the Zalinski affair was ended Holland reluctantly returned to work for private firms as a draftsman.

1886-1893

Holland himself continued to eke out a living as best he could, holding positions as a draftsman. On January 17, 1887 at age 45 he married Margaret Foley in Brooklyn and their first child, John Jr. was born in the next year. Unfortunately the child died in infancy. John and Margaret would go on to have six more children, another of which died as an infant.

In 1888 the fog of tradition was slowly lifting in the Navy Department and progress was being made. They held an open competition for the design of a submarine torpedo boat. LT William Kimball, the same officer that tried to get Holland a job with BuOrd, convinced the Secretary of the Navy of the need to investigate the potential of the submarine. The specifications drawn up for the 1888 competition were quite advanced for the time: speed 15 knots on the surface and 8 knots submerged, be able to remained submerged for up to two hours at a time, a test depth of 150 feet, complete a turn within a radius of four times its length, deliver a torpedo with a warhead of 100 lbs, and carry provisions for 90 hours of operation. Holland had a design ready to go and even had an arrangement with the prestigious Cramp & Sons Shipbuilding in Philadelphia to produce the boat. Three others submitted designs as well, but Holland's reputation had preceded him and he was declared the winner of the competition.

Then, just as the results were released, Secretary of the Navy William C. Whitney had a sudden change of heart. Likely due to political and internal pressure he abruptly canceled the competition, leaving Holland in the lurch. The incoming Harrison administration did not support the idea either, instead preferring to build up the surface fleet. Holland was totally deflated at this double defeat, and accepted a job once again as a draftsman with the Morris & Cummings Dredging Company. Holland had conferred with engineer Charles Morris during the fitting out of the Fenian Ram, and Morris was more than happy to take Holland on at the company. Holland worked for Morris & Cummings until 1893, content with the steady, if not unremarkable, income.

Holland V (Plunger of 1895)

Frost proved to be quite prescient as on March 3, 1893 Congress approved funds of $200,000 to build a working submarine. A board of three officers was formed to evaluate design submissions and cost estimates and submit recommendations to the Secretary of the Navy. A few weeks later the Holland Torpedo Boat Company was formed with Frost as the secretary-treasurer and Holland as the general manager.

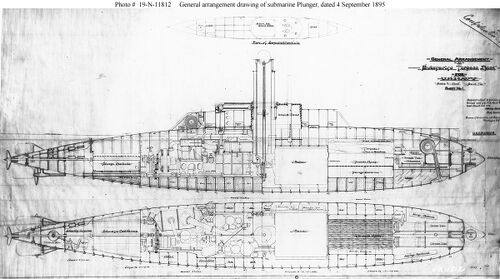

By June, Holland was ready with his design for this new competition. It was to be 85 feet long and 11 feet wide. Holland finally abandoned the idea of a single propulsion source. He chose an improved Brayton engine for surface propulsion, and the brand new technology of electric batteries and a 70 hp motor for submerged propulsion. The batteries could be recharged by a dynamo attached to the propulsion train. It would have a single axial mounted propeller. Sufficient compressed air would be carried to allow submerged runs of up to twelve hours (perhaps a stretch given the limitations of the batteries), and could launch Whitehead torpedoes from a single tube using compressed air.

The Navy favored Holland's design, but was forced to consider the entry of inventor George Baker, who actually had a working prototype boat already under testing in the Detroit River. In addition, a young Simon Lake entered the fray, submitting a design of his own. Baker ran into significant technical difficulties with his boat during testing, and political maneuvering and legal challenges by Baker and Lake did nothing for them other than delay the awarding of the contract for quite some time. It was not until March of 1895 that Secretary of the Navy Hilary Herbert finally declared that Holland was the winner of the competition and awarded the Holland Torpedo Boat Company a contract for $200,000.

Holland's initial enthusiasm for the project was quickly sobered. While the Navy was making great progress in reforming policy and modernizing its ancient fleet, there was still a tremendous amount of "tradition inertia" to overcome. The attitude of "this is always how we have done things" caused uncertainty and a reluctance to change. In addition there was simply no experience within the Navy in the area of submarine design and operation. To make up for a lack of experience, the Navy, in particular the Bureau of Steam Engineering, fell back on what they knew.

Almost immediately after signing the contract the Bureau dictated that the new submarine be propelled by a steam engine. Their unfamiliarity with the Brayton engine caused them to mistrust it. They were also uncomfortable with a single propeller shaft and dictated that the boat have two. Holland could not find a way of getting a single electric motor to turn two shafts so he retained the axial propeller and simply added two additional shafts. There was an insistence that the boat be able to hover underwater so a requirement was written that dictated vertical propellers be installed. Another requirement foisted on Holland was the need to go from a fully surfaced condition on the steam engine to fully submerged on the battery in one minute. The Bureau of Ordnance chimed in and specified that the boat have two torpedo tubes, despite that Holland's design only had one. This would necessitate a complete redesign of the bow.

As can be seen by this diagram of the approved design, the boiler and the steam engine dominated the interior of the boat. What seemed to be lost on the Navy was the fact that the heat generated by the boiler would roast the crew alive, particularly after shutting it down and submerging, which left no place for the heat to go. The large smokestack needed to maintain the necessary draft in the boiler was a huge opening in the pressure hull, requiring large valves to close it off. The engine room was very cramped, making it difficult to do any sort of maintenance.

Holland became quickly disenchanted with the project, disgusted at the ignorance and intransigence of the Navy. By the end of 1895 he had become convinced that the boat would fail, but contractual obligations kept him moving forward.

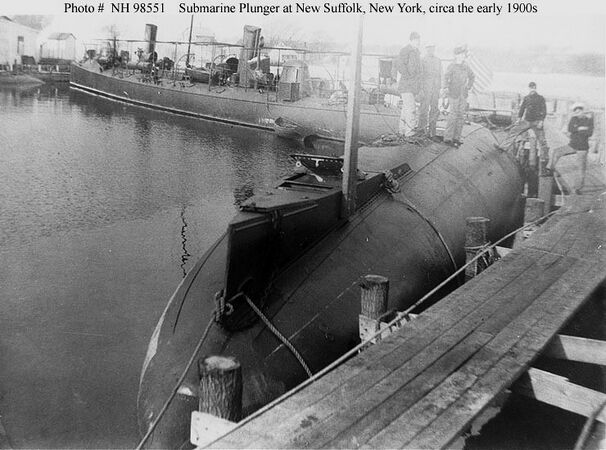

The photo on the right shows Plunger under construction in 1896 at the Columbian yard in Baltimore. On the far right the triple propellers can be seen, along with the rather small rudders above and below the center propeller. The smokestack has yet to be installed amidships, and on the far left the pointed breakwater can just be seen at the bow.

Plunger was launched on August 7, 1897. Holland was mortified as the boat rolled heavily and nearly capsized when it hit the water. It did right itself and was moved to a nearby pier for fitting out. By this time Holland and his partners had moved on to the self-financed Holland VI project, which they built without Navy interference as the ultimate expression of Holland's ideas. The legal provisions of the Plunger contract forced Holland to continue work on project, but it had no priority and work moved forward at a snail's pace. Eventually "completed", dockside trials confirmed all of Holland's worst fears. The boat got underway for only very shorts periods, never leaving Baltimore Harbor. It never submerged. By 1898 even the Navy understood that no progress was being made and any interest in the project rapidly waned, especially once Holland began demonstrating the clearly superior Holland VI. The Navy never officially accepted or commissioned the Plunger, and it remained a Holland Torpedo Boat Company (HTBC) asset.

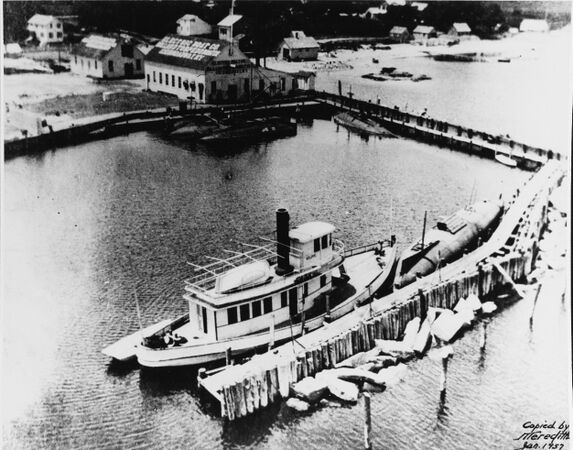

The project lingered with little work being done until January 31, 1900. At that point, the Navy Department realized that the Plunger could not be made to work as built, and with the looming acceptance of the much more advanced Holland VI into service they gave permission for the HTBC to removed the steam engine and replace it with an internal combustion (gasoline) engine. Holland and his associates held out some hope that the company could get the boat into service and accepted by the Navy by replacing the engine. The boat was hauled down Chesapeake Bay on a barge to the James River and then up to Richmond, VA. The William R. Trigg shipyard there had been contracted to do the engine work. The photo at left shows the Plunger being hauled up off the barge to a building slip on Chappell Island, March 1900. Before any real work was started negotiations with the new engine manufacturer fell through.

By June the Navy had enough and sought to wash their hands of the affair. Holland VI had been accepted and commissioned as the Navy's first submarine, and plans were afoot for an improved Holland model. The Navy agree to cancel the Plunger contract if HTBC/EB paid back the $85,000 they had already been paid for it. Holland, Frost, and company president Issac Rice immediately agreed, with the prospect of getting this albatross off the company's neck too good to pass up despite the financial hit.

The decrepit and dilapidated Plunger was reloaded on the barge and towed all the way up to the new HTBC/EB facility at New Suffolk, New York out on Long Island. Why it wasn't immediately dismantled for the scrap value is not known. Perhaps Holland and Rice believed that it could still be made to work somehow so that they could recoup some of their investment, or perhaps lingering legal issues from the canceled contract prevented them from disposing of it. At any rate the hulk sat moored at New Suffolk until 1905 when the facility was closed. What happened to the Plunger after that point is not clear, with one account stating that it was scrapped in 1917.

-

Plunger at the pier in New Suffolk, circa 1901. The USS Winslow (Torpedo Boat No. 5) is moored in the background.

-

The New Suffolk facility, 1902. The hulk of the Plunger can be seen in the right of the photo, moored next to the EB owned tug Kelpie.

U.S. Navy photos.

The Electric Boat era and Holland's later years

Page created by:

Ric Hedman & David Johnston

1999 - 2023 - PigBoats.COM©

Mountlake Terrace, WA, Norfolk, VA

webmaster@pigboats.com