192 salvage: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Pbcjohnston (talk | contribs) Added new salvage photo and rewrote some captions |

||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

[[File:Squalus Salvage 1.jpg|left|500px]] | [[File:Squalus Salvage 1.jpg|left|500px]] | ||

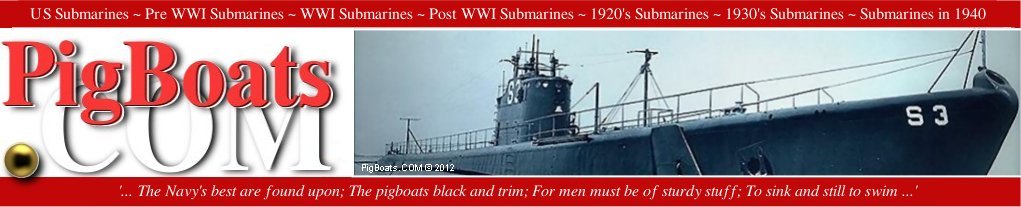

The three and a half month process of salvaging the Squalus was particularly arduous due to the operating depth of 240 feet. This forced the team to use the newly developed mixed-gas diving system, using a the highly modified Mk 5 deep water diving dress. 628 dives were made to rig lifting chains under the hull and attach pontoons. This photo shows a lifting attempt on July 13, 1939. Unfortunately, the boat rose uncontrollably with the bow breaking the water before | The three and a half month process of salvaging the Squalus was particularly arduous due to the operating depth of 240 feet. This forced the team to use the newly developed helium/oxygen (helios) mixed-gas diving system, using a the highly modified Mk 5 deep water diving dress. 628 dives by 53 divers were made to rig lifting chains under the hull and attach pontoons. This photo shows a lifting attempt on July 13, 1939. Unfortunately, the boat rose uncontrollably with the bow breaking the water before it slipped the chains and sank back to the bottom. The work of rerigging the chains and pontoons had to start all over again. | ||

<small>National Archive photo.</small> | <small>National Archive photo.</small> | ||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | |||

[[File:Squalus breaking surface.png|left|500px]] | |||

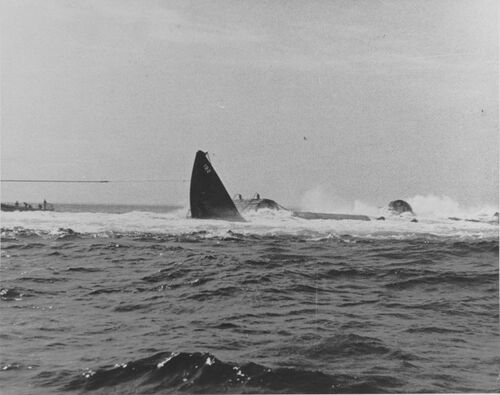

After the abortive July 13 lift attempt, 20 more days were needed to re-rig the chains and pontoons. The boat was brought to the surface in a series of controlled lifts and prepared for towing to Portsmouth. Squalus is shown here On August 12, having just broke the surface. Two pontoons are visible, and one more is about to break the surface on the port bow. This view is looking forward along the port side. | |||

<small>Photo courtesy of the Massachusetts Digital Commonwealth.</small> | |||

[[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | [[File:Red bar sub new.jpg]] | ||

[[File:Squalus under pontooms.jpg|left|500px]] | [[File:Squalus under pontooms.jpg|left|500px]] | ||

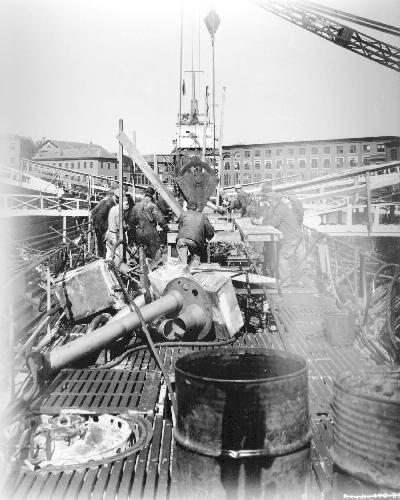

The last phase of the salvage had Squalus nearly at the surface and under tow to Portsmouth. She is shown here with part of her superstructure and fairwater above the surface, just outside of the Piscataqua River enroute to Portsmouth, | This photo was taken after the one above, during the towing phase. The last phase of the salvage had Squalus nearly at the surface and under tow to Portsmouth. She is shown here with part of her superstructure and fairwater above the surface, just outside of the Piscataqua River enroute to Portsmouth, August 1939. She is heeled far over to starboard. | ||

<small>U.S. Navy photo 326-39 via Navsource.org.</small> | <small>U.S. Navy photo 326-39 via Navsource.org.</small> | ||

| Line 59: | Line 66: | ||

[[File:Squalus recovered 3.jpg|left|500px]] | [[File:Squalus recovered 3.jpg|left|500px]] | ||

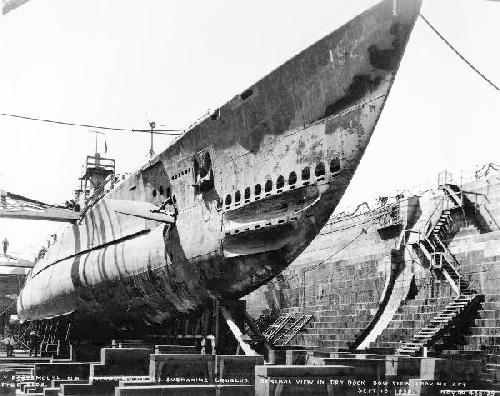

This view of the front of the conning tower fairwater shows how the pilothouse sustained damaged during the salvage operation. It would be cut away and replaced during the repair phase. | This view of the front of the conning tower fairwater shows how the pilothouse sustained damaged during the salvage operation. It would be cut away and replaced during the repair phase. | ||

The salvage effort was monumental in nature and the accomplishment of the team can not be understated. Four enlisted divers were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions during the rescue and salvage phase, and 17 enlisted and one officer were awarded the Navy Cross. A truly great effort indeed. | |||

<small>Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.</small> | <small>Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.</small> | ||

Revision as of 20:22, 21 October 2024

Rescue Operations

Photo NH 57508 courtesy of the NHHC.

The McCann chamber alongside the Falcon as it prepares for a dive on the sunken Squalus, May 24, 1939. A total of five trips were made to the sub, under very difficult conditions. At one point, frayed cables trapped the chamber underwater and a rescue of the rescuers was needed. All 33 men in the forward compartments were returned to the surface.

Photo NH 97292 courtesy of the NHHC.

Rescued crew on the deck of the USCGC Harriet Lane. The Squalus' Commanding Officer, LT Oliver F. Naquin, is standing hatless in the center, between the lifeline and the sailor behind him. He was the last man out of the boat. His calm and decisive demeanor provided courage and hope to his crew while they awaited rescue. His leadership was outstanding.

National Archive photo.

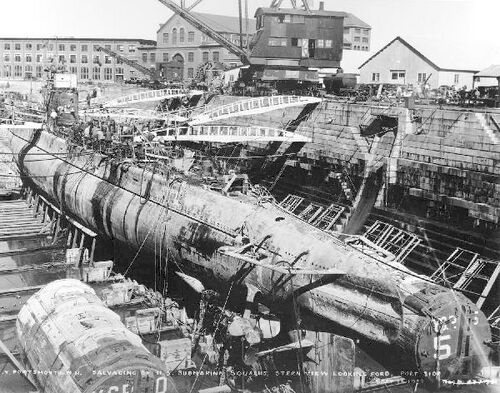

Salvage Operations and the Return to Portsmouth

The three and a half month process of salvaging the Squalus was particularly arduous due to the operating depth of 240 feet. This forced the team to use the newly developed helium/oxygen (helios) mixed-gas diving system, using a the highly modified Mk 5 deep water diving dress. 628 dives by 53 divers were made to rig lifting chains under the hull and attach pontoons. This photo shows a lifting attempt on July 13, 1939. Unfortunately, the boat rose uncontrollably with the bow breaking the water before it slipped the chains and sank back to the bottom. The work of rerigging the chains and pontoons had to start all over again.

National Archive photo.

After the abortive July 13 lift attempt, 20 more days were needed to re-rig the chains and pontoons. The boat was brought to the surface in a series of controlled lifts and prepared for towing to Portsmouth. Squalus is shown here On August 12, having just broke the surface. Two pontoons are visible, and one more is about to break the surface on the port bow. This view is looking forward along the port side.

Photo courtesy of the Massachusetts Digital Commonwealth.

This photo was taken after the one above, during the towing phase. The last phase of the salvage had Squalus nearly at the surface and under tow to Portsmouth. She is shown here with part of her superstructure and fairwater above the surface, just outside of the Piscataqua River enroute to Portsmouth, August 1939. She is heeled far over to starboard.

U.S. Navy photo 326-39 via Navsource.org.

Squalus and her pontoons alongside berth #6 at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, Kittery, Maine, September 15, 1939. Back at Portsmouth at last, several days were spent stabilizing the boat so that she could be transferred to the drydock. Only her forward half is above water. She will have to be on an even keel before entering the dock.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

Squalus at berth 6 for pumping out at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, September 15, 1939. The front of the conning tower fairwater shows damage caused by lifting pontoons hitting it during the lifting process. This photo was taken a little later than the one above. The pontoon in front of the sub is missing. This snapshot, greatly enlarged, was taken looking across the deck of another submarine, quite possibly the Sculpin. The after torpedo loading hatch and aft rescue buoy are seen on the Sculpin.

Photo in the private collection of Ric Hedman.

This view of the front of the conning tower fairwater shows how the pilothouse sustained damaged during the salvage operation. It would be cut away and replaced during the repair phase.

The salvage effort was monumental in nature and the accomplishment of the team can not be understated. Four enlisted divers were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions during the rescue and salvage phase, and 17 enlisted and one officer were awarded the Navy Cross. A truly great effort indeed.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

In Drydock

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

Now down on the keel blocks, yard crews begin the ghastly task of entering the aft part of the boat to retrieve the bodies of the deceased.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

In this view of the aft deck of Squalus in the drydock at Portsmouth, workers are preparing to remove bolted on soft patches in the pressure hull above the engine rooms. This will make removal of the bodies easier, and to expedite the refurbishment of equipment. The aft rescue/messenger buoy, (seen in the left foreground), which sadly was not released because nobody had time to release it before they drowned.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

Here men are standing on top of the engines while work proceeds to remove the dead. The large pipe was used to ventilate the interior of the boat. A lot of hazardous gasses had built up over the months.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

Squalus in the now empty drydock, September 15, 1939. Eight months of intensive work laid ahead to get her reconditioned for service.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

A view from the bow looking aft in the drydock. Her two starboard torpedo tubes are visible, along with the rigged out bow planes and one of her anchors.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

A view from the drydock caisson wall, looking forward along Squalus, September 16, 1939. Note lifting chain draped over port propeller shaft just forward of the screw. Two of the salvage pontoons are sitting in the dock alongside the boat, they would be later lifted out by cranes.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

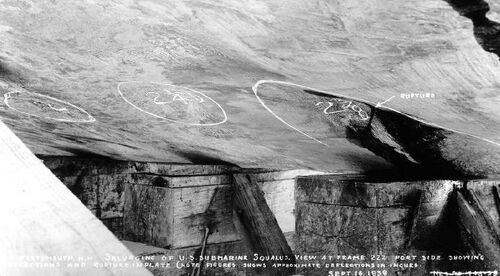

Damage to the hull near the rudder skeg caused by the pontoon lifting chains. Deep water salvage is tricky work. Even with highly skilled men working very carefully, some additional damage from the salvage work is inevitable.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

This shows the lower part of the hull near the keel. It highlights further minor damage caused by the lifting process.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

This is the port side bilge keel, showing deformities cause by lifting chains.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

Interior views post-Salvage

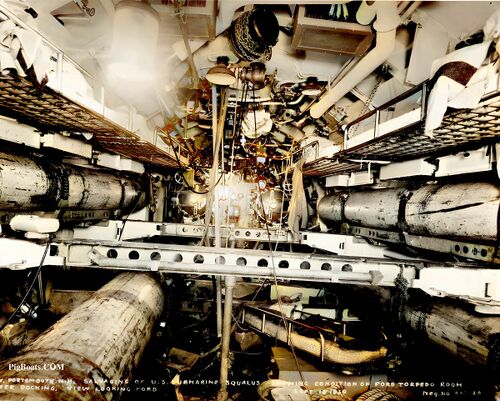

Once the boat was in the dock, dewatered, and aired out a thorough survey was done to determine the amount of repair work needed. This photo shows the forward torpedo room looking forward. The crew gathered here in the cold and darkness while they awaited rescue.

It is interesting to note that in this photo and the one below the Squalus was not carrying torpedoes, but wooden "shapes" used to check the function of the tubes, the firing mechanisms, and the handling equipment. The individual wooden slats that went into making the shapes can be seen where an actual torpedo would have a smooth metal surface. These shapes were the exact size and configuration of an actual Mk 14 torpedo and would be launched out of the tubes and pop to the surface to be recovered. They had no propellers, motors, warheads, or any internal systems.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

The forward torpedo room looking aft. The ladder leading up to the forward escape trunk can be seen just behind the torpedo rack brace. It was up this ladder that the men moved to get into the McCann chamber. The two perforated steel bars in the center of the picture were removable rails used to move the outboard reload weapons into position to load into the tubes. They were normally removed and stowed below the walking deck when not in actual use. Why they are in place here is not known.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

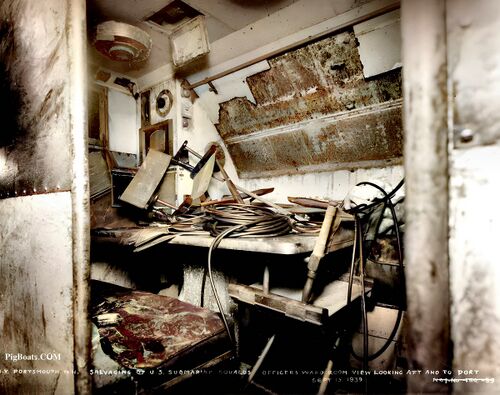

The wardroom in the forward battery compartment where the officers ate their meals. The view is looking aft and to port. The actual battery well is below the deck. This was one of three compartments that did not flood, but the long time in high humidity conditions has loosened the cork insulation applied to the pressure hull and it has begun to peel off. The jumbled nature of the room is likely due to being tossed about during the salvage operations. The entire forward battery compartment had to be abandoned during the rescue phase out of concern of chlorine gas buildup from the battery.

The wardroom had two entrances. This is the forward one where this photo was taken. The chair on top of the table normally would be placed at the other end of the table like the one see on the right.

Typically, the Captain sat in the after chair and the least senior officer (who was normally the Supply Officer) sat in the one at the forward end. The Executive Officer sat at the Captain's right and Engineering Officer sat at the Captain's left.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

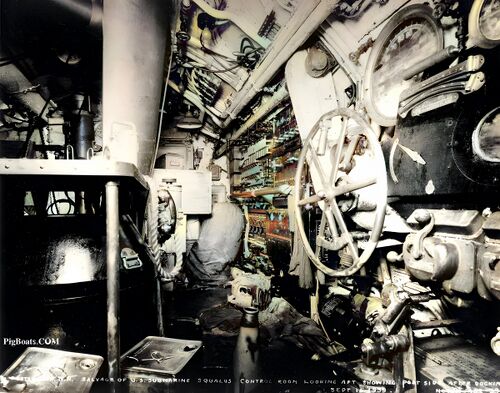

Condition of the Squalus' control room after the boat was salvaged. View is looking forward and to port. The helm wheel is on the right. The two large wheels, left, are the stern and bow plane control wheels. The levers in the middle are for the main ballast tank vents and Kingston valves. The duct work at the top is temporary and is providing air via topside fans for drying the boat out. It may also be used for venting gases from the battery wells since the battery electrolyte and saltwater form poisonous chlorine gas. A Navy Battle Lantern sits on the table in the center of the compartment.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

This is the control room looking aft at air manifolds and the sonar equipment. This was taken from the exact opposite angle as the photo above. The chart table is in the foreground, and the tube for the conning tower periscope is on the right. Mounted just to the right of the sonar equipment is a crescent shaped bubble clinometer used to determine whether the boat was on an even keel athwartships. The temporary ductwork for drying and ventilating the boat is quite visible here. Same Battle Lantern as seen above.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

The control room looking aft along the port side. The stern planes control wheel and depth gauges can be seen on the right, with the gyrocompass and chart table on the left. The control room stayed dry after the sinking, but was eventually abandoned because the escape trunk where the McCann chamber mated was in the forward torpedo room.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

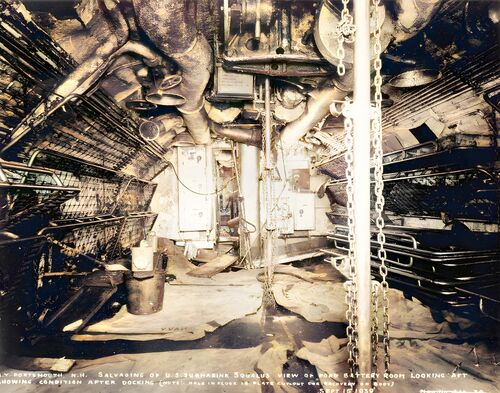

The caption written on the photo says that this is the forward battery compartment looking aft, but that is in error. This is actually crew's berthing above the after battery looking aft towards the crew's mess. This compartment was completely flooded as the boat sank. The plank shown just left of center in the photo is spanning a hole cut in the deck to remove a body of a crewman that was trapped below decks. Photo taken September 15, 1939.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

This view is in the crew's mess looking forward into the berthing compartment. Through the doorway just right of center can be seen the bunks of the crew's berthing space above the after battery. Squalus and several of her sisters had the "normal" arrangement of the after battery spaces reversed. Most boats had the crew's mess forward of the berthing compartment.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

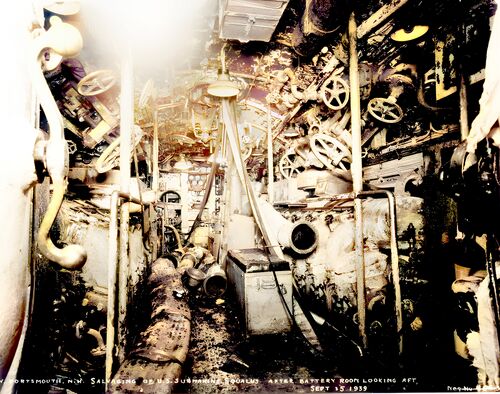

Once again, the photographer misidentified the picture as the after battery compartment. Though it is "technically" correct as it seems the photographer was standing in the after battery and took the picture through the open watertight door. The door itself is seen on the left. The view is into the forward engine room looking aft. Two of her General Motors-Winton 16-248 engines can be seen on either side of the walkway. This compartment, along with all others aft of this point were completely flooded.

Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, N.H.

Page created by:

Ric Hedman & David Johnston

1999 - 2023 - PigBoats.COM©

Mountlake Terrace, WA, Norfolk, VA

webmaster at pigboats dot com