Beaumont

Francis Hugh Beaumont

All Photos from the Francis Hugh Beaumont Jr Estate and in the Private Collection of Ric Hedman

Francis Hugh Beaumont (Jr), “Beau" as he was known in the Navy, was born on March 2, 1905 in St Paul, Neosho County, Kansas, a small town in the Southeast of the state. Francis' father, Francis Hugh Beaumont (Sr), doesn't seems to be in the picture most of his life since his parents divorced in 1910. His mother, Sadie, never remarried. By age 14 he was working as a Roustabout in the Oklahoma oil fields while still going to school.

In 1923 he was 18 years old and living in Detroit, Michigan and obtained a Michigan drivers license, perhaps he was going to college. He was still there in January 1928 when he had a pistol he owned pass a safety inspection.

In 1930, at age 25, he is back home and living with his mother, Sadie K Beaumont and older sister, Vivian, she was 6 years older than Francis, in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, which had been the families home of record for 20 years. Both he and his sister Vivian were employees of an unnamed oil company. His sister as a Stenographer and Francis doing 'Clerical' work, perhaps for the same oil company. Maybe the college education got him out of the oil fields an into the office. Vivian seems to have gone by her middle name 'Lucile'. His mother died 1933.

He, also, seems to have been active or have an active interest in politics as he traveled to Washington DC several times in the 1930's. He obtained visitor passes from his state legislator to the visitors gallery to observe legislative sessions.

To his sister, Lucile B Hoskins, a fellow Bartlesville resident, he sent a three month newspaper subscription to for the Daily and Sunday Honolulu Advertiser. Lucile shows up in post war photos.

Francis joined the Navy in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, probably the closest recruiting office to where he lived. It is noted in his records as being 'USNR' meaning he was a Navy Reservist rather than Regular Navy. Perhaps, due to his age joining the Reserves was his only option and then volunteering for active duty. It could be his job with the oil company made him draft exempt as it was a vital war industry. He was 37 at the time of his enlistment on June 15, 1942 making him one of the older men at all his commands.

Being older means he had developed a wider social life than the men just out of high school or in colleges that had entered the military. He was all ready involved in organizations like the Masons and Shriners which he continued membership and attendance in, when possible, throughout the war. We have evidence in his paperwork that on June 26, 1943 that he asked for and got one days leave while aboard the USS Salmon to attend a Shrine ceremony in Honolulu. He continued to receive Shrine and Masonic mailings and correspondence throughout his time in the Navy.

Beaumont's first several months in the Navy seem to be a blank, most likely basic training and Torpedoman's school. He was transferred to the Receiving Station in San Francisco and then on to the submarine, USS-Pike SS-173, on December 19, 1942. He was a TM/3 at the time. Pike had been in the yards at Mare Island for an overhaul since June. She had already made 4 war patrols when he reported aboard. When Pike left the yards he rode her to Hawaii and was then transferred to ComSubDiv-21 working in relief crews on subs returning from war patrols. The USS Pickerel SS-177 was the Flagship for ComSubDiv-21.

January 21, 1943 Beaumont, now working for ComSubDiv-44, sailed from Hawaii as a passenger aboard the USS Midway AG-41 for the Navy Base on Midway Island with verbal orders as to what duties he was to perform. There is no mention of what the 'special assignment' orders were. He returned to Hawaii from Midway eight days later, on Jan 29, 1943, again, aboard the USS Midway.

The Midway was renamed as the USS Panay AG-41 on April 3, 1943 to free up the name for the Navy's newest Aircraft Carrier. She was a commercial cargo ship leased by the U.S. Navy during World War II. She was used as a cargo ship and as a troop transport in the North Pacific Ocean. She was returned to her owner at war’s end.

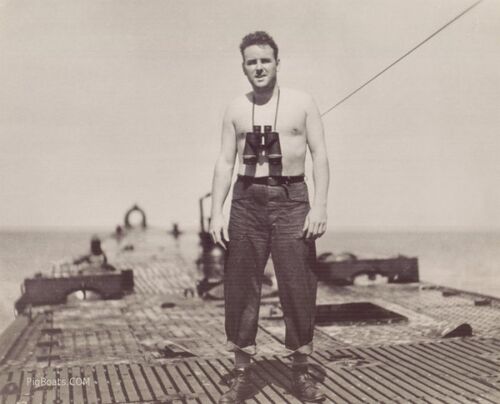

He was transferred to the submarine USS Permit SS-178 at Midway from ComSubDiv-21 on March 29, 1943, he was a TM/2 by this time. Permit departed Midway on April 6, 1943 on her 8th war patrol to search for Japanese ships in the traffic lanes between the Marianas Islands and Truk Atoll in the Caroline Islands.

Permit had several encounters with the Japanese on this patrol. On May 5, at eight o'clock in the morning, from a submerged periscope attack, she fired a four torpedo spread at the Tokai Maru of 8,359 tons, resulting in one hit and damaging her. On May 11, at one o'clock in the morning, during a night surface action using her radar she attacked three ships. One was claimed to have been a 10,000 ton cargo ship the other two were thought to have been 5000 tons each. Permit claimed to have sunk the 10,000 ton vessel and one of the 5000 ton ships and damaged the other. There is no post war verification of these sinkings in this action. Permit returned to Pearl Harbor May 25, 1943.

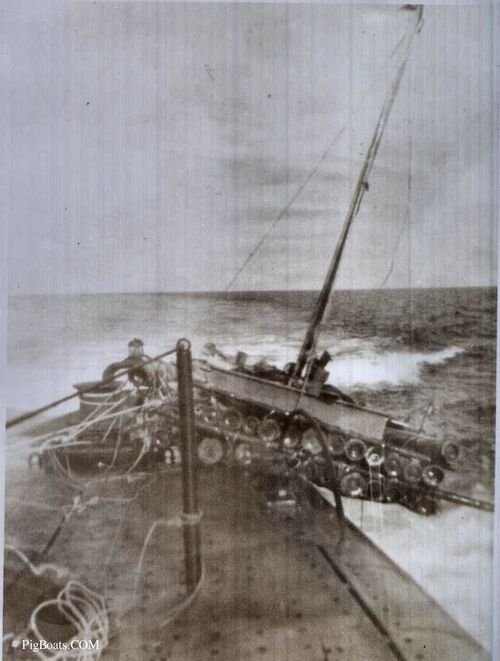

The photo of Francis Beaumont, above, was taken on the fore deck of the Permit during this patrol. He was now 38 years old. The large rectangular blocks seen on both sides, behind him, are part of the breech mechanism for the two under deck mounted torpedo tubes installed in January 1943 at Mare Island. These tubes proved problematic and were not installed in boats beyond the few original conversions. The torpedoes were hard to maintain and there seemed to be some concern they might explode when undergoing depth charging. There are accounts of torpedoes having hot runs in these tubes. Many skippers had them removed.

The earlier fleet boats had been built with four tubes forward, instead of the six wanted by the crews and skippers, due to government efforts to try and keep costs and weight down. The later fleet boats were built with six tubes forward starting with the Tambor Class. Being a Torpedoman Beaumont would have had these tubes as part of his job aboard Permit. It is not known if he was assigned to the forward or after torpedo room.

Two days after Permit's return to port, on May 27, 1943, Beaumont was transferred back to Relief Crews at ComSubDiv-44. There is no reason given as to why he was transferred off the boat. Maybe it was that Permit and he were not a good fit or he was just filling a temporary billet.

During this time between submarines he managed to travel to the big island of Hawaii and climb to the top of the Kilauea volcano and be photographed there and receive a certificate attesting to that fact on June 16, 1943.

He remained working for either ComSubDiv-44 or ComSubDiv-21 until September 10, 1943 when he reported to his next submarine, the USS Salmon SS-182, Lt. Cdr. Nicholas J. Nicholas in command, bound to sea for her eighth war patrol. She left Hawaii on September 27, 1943. This war patrol saw her return to the Kuril Islands where she had patrolled previously.

On this patrol she is credited with damaging two freighters. The first one was on October 15 at 2 o'clock in the afternoon on a 6000 ton cargo ship she hit with one torpedo out of seven fired in a daylight submerged periscope attack. The second attack was on October 28 at 2 o'clock in the morning while submerged using her periscope. One torpedo hit was scored from four torpedoes fired, damaging the the ex-patrol vessel Nagata Maru of 2960 tons. This patrol ended on November 17, 1943 when she returned to Pearl Harbor. Hard work for the torpedo gangs for such small returns, 11 torpedoes fired for two hits and no sinkings.

Beaumont seems to have finally found a home. The ninth war patrol for Salmon was conducted between December 15, 1943 and February 25, 1944. On January 22, 1944, about 500 miles south of Yokohama, she succeeded in damaging a tanker of approximately 4000 tons. In a submerged, evening twilight attack Salmon fired a 4-torpedo spread scoring 3 hits, but the ship did not sink. Escorts probably harassed Salmon until the ship could escape.

On April 1, 1944 Salmon, now under the command of Lt. Cdr. Harley K. Nauman, departed on her tenth war patrol from Pearl Harbor enroute to Johnston Island in company with the submarine USS Seadragon SS-194. She was assigned a special photo reconnaissance mission for this patrol which would assist in preparing plans for gaining control of the Caroline Islands. She conducted a reconnaissance of Ulithi Atoll, (which was to become a large repair and staging base for the US Navy), from April 15 to April 20; Yap from April 22nd to April 26th; and Woleai between April 28 and May 9, 1944. She returned to Pearl Harbor on May 21 with much valuable information that was utilized in last minute changes to the assault plans.

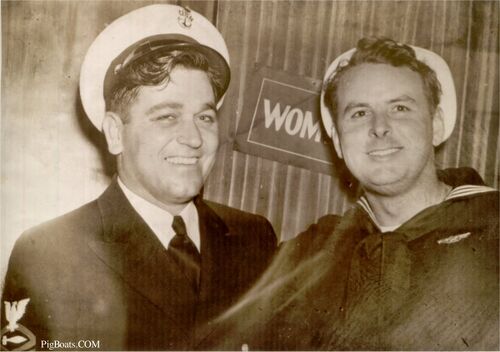

Between Salmon's tenth and eleventh war patrols Salmon may have had some sort of overhaul at Mare Island because on July 28, 1944 in the Bay area Beaumont had his photo taken with a shipmate, the newly frocked Chief Torpedoman, Robert L Olmstead of the Salmon.

September 4, 1944 Francis Beaumont was promoted to TM/1 (T) while attached to Salmon.

Salmon's eleventh and last war patrol was to be one of heroic and epic proportions, becoming one of the legends of WW II submarine warfare. This patrol was conducted in company with submarines USS Trigger SS-237 and USS Sterlet SS-392 as a coordinated attack group in the Ryukyu Islands. This patrol began on September 24, 1944. On October 30 , Salmon attacked a large tanker that had been previously damaged by Trigger. This attack began in the late afternoon and continued on into the night. The tanker was protected by four antisubmarine patrol vessels which were cruising back and forth around the stricken ship.

Salmon fired four torpedoes and made two good hits on the 10,500 ton Jinei Maru, but was forced to dive deep under a severe depth charge attack by the escorts. She leveled off at 300 feet but was soon forced to nearly 500 feet due to damage and additional pounding of the depth charges. The Salmon's depth gauge only went to 450 feet so depth was calculated from the sea pressure gauge readings. Unable to control leaking and maintain depth control, she battle surfaced into a clear night sky and a full moon spotted by rain squalls, to fight for survival on the top of the ocean. It was later determined that Salmon had gone to 578 feet.

The depth charges damaged the external main engine air induction piping and it had collapsed and flooded, causing the ship to become heavy overall, and the stern diving planes jammed in 'full dive' position. About 7000 gallons of diesel fuel was lost do to a vent riser failing on Fuel Ballast Tank number 7 and the lighter fuel being replaced by heavier sea water damaging the subs neutral trim. Depth control was immediately lost and Salmon oscillated up and down several times, remaining submerged only by blowing the safety tank and by going ahead at emergency speed with a 20 degree up angle on the boat.

Seventeen minutes after the attack, with batteries depleted, the after engine room flooded almost to the level of the main motors, and still not having achieved depth control, Salmon surfaced. She never dove again.

The enemy finally noticed the Salmon in the dark about 7000 yards away but seemed wary and held their distance while assessing the situation. This gave Salmon's crew a few precious minutes to correct a bad list and to repair some of the damage. Her torpedo tubes were useless having used up all the air necessary for firing torpedoes just to reach the surface. The crew hurriedly manned the deck gun and began bringing up ammunition for it and the 40MM and 20MM guns. .30 caliber machine guns were mounted and manned.

The vessels began to close, firing at each other at great distance with little effect. The escort vessel began to close at higher speed but Salmon chose to become the aggressor and not run. Captain Nauman turned on the attackers and charged them, passing within 50 yards down the side of the attacking vessel, raking her with withering machine-gun and 20mm gunfire, also her 40mm and her 4" deck guns poured rounds into the ship as fast as the crews could load them. Later reports stated that 29 of the Japanese crew had been killed in that attack. The patrol escort vessel, IJN CD-22, came to a stop due to the damage. Salmon had come so close that the Japanese vessel could not depress her guns low enough to return fire.

Salmon then exchanged fire with a second patrol vessel which had begun her own attack but after a few rounds and hits broke off the attack and seemed to hesitate at some distance for reinforcement from the other two which were coming to the scene. Salmon began sending out plain language directions for all other subs in the vicinity to attack, giving the position of the action. Two other subs replied in plain language which was picked up by the Japanese. This probably further discouraged the enemy who, fearing the other submarines were in the area, began milling around pinging on sound gear. Salmon took advantage of a rain squall and slipped away into the dark.

Other than the damage caused by depth charges, Salmon suffered only a few small caliber hits from the enemy vessels. While stopped to repair some damage she was fired on by Japanese submarines but all missed. Sterlet and Trigger had orders to take the crew off and sink Salmon, the crew, to a man, refused to abandon ship. Escorted by Sterlet, Trigger, and USS Silversides SS-236, she made it to Saipan on three engines. She was given one third credit for a 10,500-ton tanker which was eventually sunk by a Sterlet torpedo. On November 3, 1944, she moored alongside the submarine tender USS Fulton AS-11, in Tanapag Harbor, Saipan.

On November 10, Salmon stood out from Saipan, in company with the tender Holland, and sailed via Eniwetok to Pearl Harbor. When she arrival at Pearl she created quite a commotion at the Sub Base. No one had seen a submarine with this much damage still able to float and be under her own power. The pressure hull in the after part of the Salmon was said by some to look like corrugated sheet metal. Many hull plates were dished in from the concussive force of the depth charges. After some repairs she proceeded to San Francisco and the Naval Dry docks at Hunter's Point, arriving on December 2, 1944.

There she was surveyed by the Board of Inspection and Survey a decision was made to send her to the Navy Yard, Portsmouth, N.H., for minimum damage repairs necessary to use her as a training and experimental submarine.

Sufficient repairs were made at Hunter's Point to render the ship seaworthy for her surface run to Portsmouth. Some machinery was overhauled and the hull above the waterline was painted. The hull and superstructure were left intact except for scrapping of the main engine air induction piping and renewal of damaged wooden decking. Salmon departed Hunter's Point, on January 27, 1945 with the submarine USS Redfish SS-395 as escort and proceeded, via the Panama Canal, to Kittery, ME where she arrived on February 17, 1945. Repairs to the damage were started being assessed immediately. The crew was moved off the submarine and all damaged equipment was assessed for repair.

After another survey on October 5, 1945, the Chief of Naval Operations, Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, recommended a halt of further repair work and to scrap the Salmon instead.

This damage to Salmon is considered to have been one of the most serious ever inflicted on any U.S. submarine to survive during World War II. Pressure hull deformation was extensive in way of both engine rooms.

Salmon was decommissioned on September 24, 1945 at the Naval Shipyard, Portsmouth, New Hampshire. She was Struck from the Navy list on October 11, 1945. She was scrapped on April 4, 1946.

While the sub was in San Francisco, Beau was given 18 days leave and travel time beginning December 28, 1944 to go home to Bartlesville, Oklahoma to visit with his sister Vivian/Lucile Hoskins, to whom he had sent the newspaper subscription. At the end of the leave, he was to report to the USS Stickleback SS-415 at the Portsmouth Ship yard on January 15, 1945.

Most of the crew, including Francis Beaumont, were transferred from Salmon, to the USS Stickleback SS-415**, which had just been placed in commission, replacing the commissioning crew. Salmon having been declared an operational loss do to the heavy battle damage and not worth repairing, the crew was rewarded with a brand new submarine for their warrior spirit.

During this turnover period to Stickleback, Beaumont had orders to the Naval Torpedo Station, Newport, RI for training on April 7, 1945. During this training time he may have been also sent to Great Lakes for some additional training. There is a photo of him and a number of other Torpedomen out on the town at Eital's Old Heidelberg restaurant at 14 Randolf Street in Chicago along with some ladies. When training was completed he returned to Stickleback.

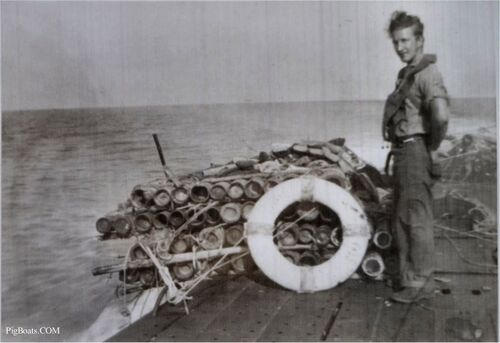

The Stickleback made one war patrol lasting just two days on station in the Sea of Japan when the war ended. She remained in the area and on August 21, 1945 sighted two bamboo rafts holding 19 survivors of a freighter, the Teihoku Maru, 5794 tons, which had been sunk 10 days before by USS Jallao SS-368. The crew were taken on board and the rafts pulled on to the after deck. For 18 hours the crew were given food, water, medical treatment. They were set afloat again a short distance from one of the Japanese islands were they could easily row ashore and could be attended to by local Japanese. Stickleback was now performing humanitarian aid assisting fellow sailors in need since the war had ended.

In this first photo the rescued sailors are being given medical treatment and food and water. Francis Beaumont is standing facing the camera in the center of the photo. At the left edge a portion of one of the rafts can be seen to the left of the mans back. Between the second and third standing men on the left the mast from the second raft can be seen meaning that this photo was taken on the aft deck of he submarine.

September 29, 1945 Beaumont was transferred to Treasure Island to begin the process for separation from the navy as TM/1 SS. His discharge took place on October 7, 1945.

During his life after the war he never married but remained a 'ladies man', according one close source, with many friends and acquaintances and few, it is intimated, that some were 'closer' than others. Francis Hugh Beaumont Jr. passed away on July 11, 1989 in Dallas Texas at 84 years of age.

During his working years he had become an accountant. He was still active in his Masonic and Shrine lodges and traveled around the country and returned to Hawaii at least once. He was a life member of the local VFW and member of the Submarine Veterans of WW II, Dallas Chapter.

He is buried at Restland Memorial Park on the northeast side of Dallas, Texas. His grave is marked by a small, plain concrete, cemetery supplied, marker much chipped by lawnmowers. We can find no data on Lucile or her passing.

Thanks you's to James Haas and Patricia Lynn for proof reading and Jim Christley for some technical details.

**Stickleback herself came to a sad ending. On 28 May 1958, Stickleback was participating in an antisubmarine warfare exercise with Silverstein (DE-534) and a torpedo retriever boat in the (Pearl Harbor) Hawaiian area. The exercises continued into the afternoon of the next day when the submarine completed a simulated torpedo run on Silverstein. As Stickleback was going to a safe depth, she lost power and broached approximately 200 yards ahead of the destroyer escort. Silverstein backed full and put her rudder hard left in an effort to avoid a collision but holed the submarine on her port side. (It is reported that Silverstein kept her bow in the hole in Sticklebacks side to try and stem the flow of water into the submarine.)

Stickleback's crew was removed by the retriever boat and combined efforts were made by Silverstein, Sabalo (SS-302), Sturtevant (DE-239), and Greenlet (ASR-10), to save the stricken submarine. The rescue ships put lines around her, but her after compartment flooded and, at 1857 hours on 29 May 1958, Stickleback sank in 1,800 fathoms of water.

Page created by:

Ric Hedman & David Johnston

1999 - 2023 - PigBoats.COM©

Mountlake Terrace, WA, Norfolk, VA

webmaster at pigboats dot com